Plain Schizura

Coelodasys apicalis Grote and Robinson, 1866

- Class

- Insecta (Insects)

- Family

- Notodontidae (Prominent Moths)

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- SU

Unrankable - Currently unrankable due to lack of information or due to substantially conflicting information about status or trends.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Moths in the family Notodontidae (Prominent Moths) hold their wings rooflike over their bodies at rest, giving them the appearance of a stick (Covell 1984).

State Ranking Justification

As of 2012, there is one known extant occurrence in New York (Suffolk County). Additional surveys are needed to determine an appropriate rank.

Short-term Trends

The short-term trends are unknown.

Long-term Trends

The long-term trends are unknown except that it was always considered uncommon (Schweitzer et al. 2011).

Conservation and Management

Threats

Known threats include habitat loss due to development and fire suppression in some habitats, although the threat of development for the remaining habitat on Long Island may be low. The suppression of fires in barrens and other dry places could cause a loss of habitat for the species and therefore a drop in population size. Conversely, a fire affecting an entire occurrence could eliminate all life stages that are present. It is assumed that fires would cause high mortality for this species (Schweitzer et al. 2011).

This species is attracted to artificial lighting. Artificial lighting can: increase predation risk, disrupt behaviors such as feeding, flight, and reproduction, and interfere with dispersal between habitat patches. In addition, many individuals die near the light source. It is not known if the impact of artificial lighting is severe, but the impact is likely greater for small, isolated populations (Schweitzer et al. 2011).

Insecticide spraying, especially Dimilin, could be harmful.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

The best management strategy for this species is the management of the natural community or habitat where it occurs. Historically, fire has played a role in maintaining maritime grasslands. The entire occupied habitat for a population should not be burned in a single year. For example, in places where prescribed burning is used, refugia (unburned areas) are needed for many species to ensure that any life stage can survive a fire. Schweitzer et al. (2011) suggests waiting five years before burning a unit again to give the lepidopteran population a chance to recolonize and increase local populations to withstand another fire. It may also be beneficial to know the locations of rare lepidopterans since localized populations may be lost if there are no individuals at the area set aside as refugia (Schweitzer et al. 2011).

Minimizing lighting to maintain dark sky conditions would be beneficial. When lighting is necessary, it's best to use lights that emit red or yellow light because insects are generally not attracted to those colors. However, many sodium lights, which emit yellow light, are so bright that they do attract some insects. The best lighting appears to be low pressure sodium lights which have little effect on flying insects (Schweitzer et al. 2011).

Insecticide use should be avoided when possible if rare species are present. When insecticide use cannot be avoided, careful planning along with consistent rare species monitoring, can result in successful eradication of the target species without eliminating rare species. Schweitzer et al. (2011) states that Bacillus thuringiensis (Btk) use to control spongy moth larvae would most likely not harm plain Schizura because the larvae are not present until about one month after spongy moth larvae.

Research Needs

Additional research is needed to determine habitat needs and the preferred foodplant in the Northeast.

Habitat

Habitat

Precise habitat needs of plain Schizura are unknown, but it's likely sandy pine barrens at the northern limits of the range. In New York, this species was found between either maritime dunes and maritime heathland or maritime heathland and sea level fen.

Associated Ecological Communities

- Maritime dunes*

(guide)

A community dominated by grasses and low shrubs that occurs on active and stabilized dunes along the Atlantic coast. The composition and structure of the vegetation is variable depending on stability of the dunes, amounts of sand deposition and erosion, and distance from the ocean.

- Maritime heathland*

(guide)

A dwarf shrubland community that occurs on rolling outwash plains and moraine of the glaciated portion of the Atlantic coastal plain, near the ocean and within the influence of onshore winds and salt spray.

* probable association but not confirmed.

Range

New York State Distribution

There is one known occurrence in Suffolk County on Long Island.

Global Distribution

This moth occurred in scattered areas from southern Maine to Wisconsin and southward, including parts of Nebraska and Kansas, to Texas and Florida, but is now very rare to historical in the eastern part of its range, except on the immediate New England coast and off-shore islands. Curiously, there is no evidence this species ever (1880-2007) occurred regularly in the New Jersey Pine Barrens where there are only two 1950s specimens; one from the northern fringe and the other labeled merely "Ocean County", so possibly not even from the barrens. In the Midwest, populations have recently been found in the Wisconsin pine barrens (Ferge and Balogh 2000) and at four places in Kentucky (Covell 1999).

Best Places to See

- Napeague State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

Identifying Characteristics

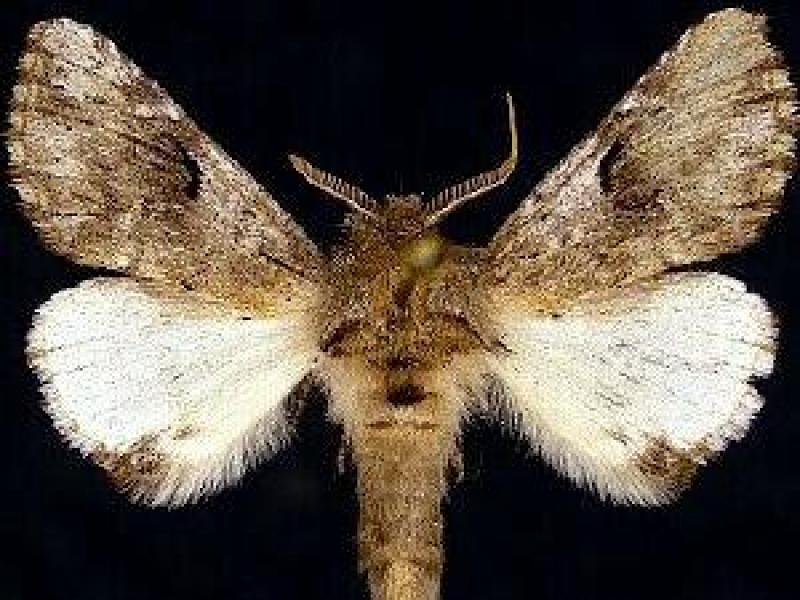

Plain Schizura has a wingspan of 2.6 to 3.2 cm. The forewing is gray with brown-shading at the base and anal angle. Indistinct, blackish lines are present on the forewing as well. The hind wing is off-white. The males have a black patch at the anal angle while the female has a "blackish" patch (Covell 1984). This species is similar to chestnut Schizura. Contrasting to the plain Schizura, the chestnut Schizura has a strikingly black thorax and the hindwing is dark brownish (Beadle and Leckie 2012). The forewing is gray with brown shading on the plain Schizura and gray with red shading and whitish on the apex for the chestnut. They both have a black reniform spot which is crescent-shaped on plain Schizura and can be crescent-shaped or shaped as a vertical dash on the chestnut Schizura. With the chestnut though, the spot joins with a blackish triangle, widening toward the outer margin (Covell 1984). They are similar in size, as chestnut has a wingspan of 3 to 3.5 cm.

Best Life Stage for Proper Identification

Adult.

Diet

The following foodplants have been recorded: bayberry, blueberry, common wax myrtle, poplars, and willows (Covell 1984). Further investigations are needed to determine others (NatureServe 2011).

Best Time to See

Adults are most likely to be encountered in June and July in the northern portion of its range.

- Present

- Active

The time of year you would expect to find Plain Schizura present and active in New York.

Plain Schizura Images

Taxonomy

Plain Schizura

Coelodasys apicalis Grote and Robinson, 1866

- Kingdom Animalia

- Phylum Arthropoda

(Mandibulates)

- Class Insecta

(Insects)

- Order Lepidoptera

(Butterflies, Skippers, and Moths)

- Family Notodontidae (Prominent Moths)

- Order Lepidoptera

(Butterflies, Skippers, and Moths)

- Class Insecta

(Insects)

- Phylum Arthropoda

(Mandibulates)

Synonyms

- Schizura apicalis (Grote and Robinson, 1866)

Additional Resources

References

Beadle, D. and S. Leckie. Peterson field guide to moths of Northeastern North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: New York, NY.

Covell, C.V., Jr. 1999. The butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) of Kentucky: An annotated checklist. Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission Scientific and Technical Series 6: 1-220.

Covell, Charles V. 1984. A field guide to the moths of eastern North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

Ferge, L. A., and G. J. Balogh. 2000. Checklist of Wisconsin Moths (Superfamilies Drepanoidea, Geometroidea, Mimmallonoidea, Bombycoidea, Sphingoidea, and Noctuiodea). Contributions in Biology and Geology of the Milwaukee Public Museum No. 93. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. 55 pp. and one color plate.

Forbes, William T. M. 1948. Lepidoptera of New York and neighboring states part II. Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station Memoir 274.

NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: April 17, 2012 ).

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Schweitzer, D.F., M.C. Minno, and D.L. Wagner. 2011. Rare, Declining, and Poorly Known Butterflies and Moths (Lepidoptera) of Forests and Woodlands in the Eastern United States. USFS Technology Transter Bulletin, FHTET-2009-02.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Hollie Y. Shaw

Information for this guide was last updated on: June 28, 2012

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coelodasys apicalis.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/plain-schizura/.

Accessed April 19, 2024.