Blacknose Shiner

Notropis heterolepis Eigenmann and Eigenmann, 1893

- Class

- Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fishes)

- Family

- Cyprinidae (minnows and carps)

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2S3

Imperiled or Vulnerable in New York - Very vulnerable, or vulnerable, to disappearing from New York, due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign either S2 or S3.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G5

Secure globally - Common in the world; widespread and abundant (but may be rare in some parts of its range).

Summary

Did you know?

The blacknose shiner has a black lateral stripe that extends all the way from the tip of its nose to its tail. It is dependent on aquatic vegetation for forage and nursery habitat.

State Ranking Justification

The blacknose shiner has declined in at least some of the watersheds where it is found in the state although precise trends remain unclear. They may be impacted by land use practices that lead to runoff and siltation, and to the loss of aquatic vegetation.

Short-term Trends

The short-term trends are unclear. Some assessment methods show blacknose shiner has declined in at least three but maybe as many as seven of the fourteen watersheds where it is found in the state.

Long-term Trends

This species has declined roughly 30-50% from historical numbers. It is currently known to have declined in at least some of the watersheds where it is found in the state and no longer appears in the Genesee River watershed. It is known to have suffered extensive declines in other regions, such as parts of the mid-west (Roberts et al. 2006).

Conservation and Management

Threats

Blacknose shiners are threatened by increased turbidity and siltation of stream bottoms from erosion and runoff, leading to a decline in the presence of aquatic vegetation. This is especially a problem for them in the southern half of New York State. Land disturbance (clearing, logging, overgrazing) and the resulting siltation which lead to the loss of vegetated backwaters, were suggested causes for the decline of the species in the Ozarks of Missouri (Pflieger 1997). Lakeshore development can contribute to decline in some areas (Eddy and Underhill 1974). Blacknose shiners are dependent on aquatic vegetation for foraging and as nursery habitat, so activities that reduce this important resource could put them in jeopardy (Roberts et al. 2006).

Research Needs

Continued monitoring of known populations as well as a resurvey of locations where the species was recorded during the New York Biological Survey of 1926-1939 would help to better determine trends and locations where threats to persistence may occur.

Habitat

Habitat

The blacknose shiner occurs in creeks, small rivers, ponds, and in the shallower areas of lakes with aquatic vegetation. It typically inhabits clear, cool waters, usually over sand, and is tolerant of the oxygen depletion that occurs in lakes during winter (Becker 1983). They likely spawn in sandy areas as well (Becker 1983).

Range

New York State Distribution

Blacknose shiners have been found in most watersheds in the state except for the southeastern ones. They occupy watersheds in the north and west parts of the state including the Allegheny River, Black River, Chemung River, Lake Champlain, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, Mohawk River, Oswegatchie River, Oswego River, Raquette River, St. Lawrence River, Susquehanna River, and Upper Hudson River. Their primary range in New York is the periphery of the Adirondacks, western New York, and the southern tier. Historically, they were found in the Genesee River watershed but are now thought to be absent from that area.

Global Distribution

The blacknose shiner occurs across a large range spanning the Atlantic, Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and Mississippi River basins from Nova Scotia to Saskatchewan, south to Ohio, Illinois, south-central Missouri, and (formerly) Kansas. They are considered common in some parts of their range (especially Ontario, Michigan, and Wisconsin), but are disappearing from the southern part (Page and Burr 1991).

Best Places to See

- Upper and Lower Lakes WMA (St. Lawrence County)

- Tributaries of the Oswegatchie River near Heulvelton, NY (St. Lawrence County)

Identification Comments

General Description

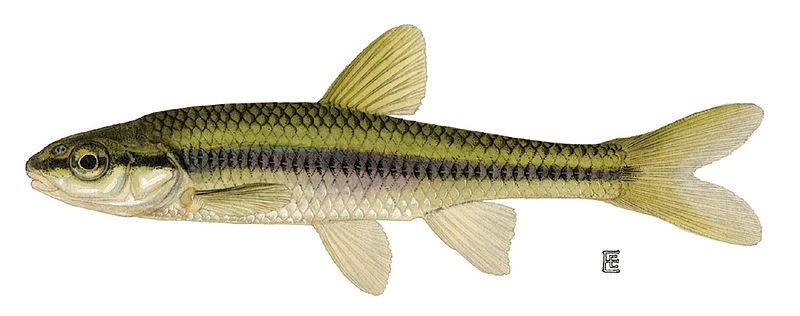

The blacknose shiner is a small minnow-sized fish that is greenish-grey in color. The have a black lateral strip starting on their nose and ending at the tail.

Identifying Characteristics

The blacknose shiner is a small minnow-sized fish that is typically only 2-3 inches in length and greenish-grey in color. The have a white lower jaw and black lateral strip running from the tip of their snout to their tail. There is a light, narrow stripe of gold scales that appears above the black stripe. The scales on the back are edged in black.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The most useful identifying charateristics are the black stripe down the side that begins on the nose and the narrow stripe of gold scales that is present above it.

Best Life Stage for Proper Identification

Adults are easiest to identify.

Behavior

Blacknose shiners are typically most active foraging in morning and at night (Roberts et al. 2006).

Diet

Blacknose shiners feed on small aquatic invertebrates. Cladoceran water fleas (Chydoridae and Bosminidae) and ostracods (a very small crustacean) were the main components of their diet in one study in Illinois (Roberts 2006).

Best Time to See

Blacknose shiners are more active during the warm months.

- Active

- Reproducing

The time of year you would expect to find Blacknose Shiner active and reproducing in New York.

Similar Species

- Blackchin Shiner (Notropis heterodon)

(guide)

The blacknose shiner appears similar to the blackchin shiner but has a smaller mouth and has an entirely white lower jaw, while the blackchin shiner has black on the tip of the lower jaw.

Blacknose Shiner Images

Taxonomy

Blacknose Shiner

Notropis heterolepis Eigenmann and Eigenmann, 1893

- Kingdom Animalia

- Phylum Craniata

- Class Actinopterygii

(Ray-finned Fishes)

- Order Cypriniformes

(Minnows and Suckers)

- Family Cyprinidae (minnows and carps)

- Order Cypriniformes

(Minnows and Suckers)

- Class Actinopterygii

(Ray-finned Fishes)

- Phylum Craniata

Additional Resources

References

Eddy, Samuel, and J. C. Underhill. 1974. Northern fishes with special reference to the Upper Mississippi valley.

Emery, L. and D.C. Wallace. 1974. The age and growth of the blacknose shiner, Notropis heterolepis (Eigenmann and Eigenmann). American Midland Naturalist 91(1): 242-243.

George, C.J. 1980. The fishes of the Adirondack Park. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Albany, NY 94 pp.

Herkert, J. R., editor. 1992. Endangered and threatened species of Illinois: status and distribution. Vol. 2: Animals. Illinois Endangered Species Protection Board. iv + 142 pp.

Lee, D. S., C. R. Gilbert, C. H. Hocutt, R. E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister, and J. R. Stauffer, Jr. 1980. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes. North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, Raleigh, North Carolina. i-x + 854 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Page, L. M., and B. M. Burr. 1991. A field guide to freshwater fishes: North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 432 pp.

Page, L. M., and E. C. Beckham. 1987. Notropis rupestris, a new cyprinid from the middle Cumberland River system, Tennessee, with comments on variation in Notropis heterolepis. Copeia 1987:659-668.

Pflieger, W.L., 1997. The fishes of Missouri Jefferson City. Missouri Department of Conservation.

Roberts, Matt E., Brooks M. Burr, Matt R. Whiles, and Victor J. Santucci Jr. 2006. Reproductive ecology and food habits of the blacknose shiner, Notropis heterolepis, in northern Illinois. The American Midland Naturalist 155: 70-83.

Robins, C.R., R.M. Bailey, C.E. Bond, J.R. Brooker, E.A. Lachner, R.N. Lea, and W.B. Scott. 1991. Common and scientific names of fishes from the United States and Canada. American Fisheries Society, Special Publication 20. 183 pp.

Scott, W. B., and E. J. Crossman. 1973. Freshwater fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 184. 966 pp.

Smith, C.L. 1985. The Inland Fishes of New York State. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 522pp.

Smith, P. W. 1979. The fishes of Illinois. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. 314 pp.

Werner, R.G. 1980. Freshwater fishes of New York State. N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. 186 pp.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Kelly A. Perkins

Information for this guide was last updated on: April 5, 2016

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Notropis heterolepis.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/blacknose-shiner/.

Accessed April 26, 2024.