Weft Fern

Crepidomanes intricatum (Farrar) Ebihara & Weakley

- Class

- Filicopsida (Ferns)

- Family

- Hymenophyllaceae (Filmy-fern Family)

- State Protection

- Threatened

Listed as Threatened by New York State: likely to become Endangered in the foreseeable future. For animals, taking, importation, transportation, or possession is prohibited, except under license or permit. For plants, removal or damage without the consent of the landowner is prohibited.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4G5

Apparently or Demonstrably Secure globally - Uncommon to common in the world, but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G4 or G5.

Summary

Did you know?

This fern exists only in the gametophyte form but at one time, before glaciation, there may have been sporophyte plants that produced spores that allowed the species to expand its range. The author of the species, Donald Farrar, postulates that the loss of sporophytes may have been due to climate change after the Pleistocene Epoch and there still exists the possibility that they remain undiscovered somewhere in the Appalachian Mountains (Farrar 1992).

State Ranking Justification

There are now six extant populations known from the southern tier and central New York. There are four historical populations from the Catskills and Hudson Valley area that have not been surveyed.

Short-term Trends

The short-term trend is unknown.

Long-term Trends

The long-term trend is unknown since there is no good quantity data on populations.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The plants are generally in protected crevices within outcrops or cliffs. Long-term drying of the sites, or scaling or heavy recreational use are potential threats.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

More research is also needed on the proper management procedures to protect and increase populations.

Research Needs

Research is needed into how climate change will affect these populations and the type of habitat they prefer. More research is also needed on the proper management procedures to protect and increase populations.

Habitat

Habitat

In New York, Appalchian Bristle Fern has been found on ledges of conglomerate rock amongst large mossy boulders, on rock houses of sandstone conglomerate, and in crevices in calcareous shales in the gorges of the Finger Lakes (New York Natural Heritage Program 2024). On basic and acidic rock in sheltered caves, pockets, and crevices (Haines 2011). Deep shade of non-calcareous rock houses (Rhoads and Block 2000). On non-calcareous rocks in deeply sheltered crevices and grottoes and occasionally epiphytic (Flora of North America 1993). Rock houses and moist, overhanging cliffs, usually on sandstone (Gleason and Cronquist 1991).

Associated Ecological Communities

- Acidic talus slope woodland

(guide)

An open to closed canopy woodland that occurs on talus slopes (slopes of boulders and rocks, often at the base of cliffs) composed of non-calcareous rocks such as granite, quartzite, or schist.

- Ice cave talus community*

(guide)

A community that occurs on rocks and soil at the base of slopes of loose rocks (often below cliffs; these are talus slopes) that emit cold air. The emission of cold air results from air circulation among the rocks of the talus slope where winter ice remains through the summer. The vegetation is distinctive because it includes species characteristic of climates much cooler than the climate of the area where the ice caves occur.

- Talus cave community

(guide)

The community that occurs in small crevices and caves with walls of boulders or cobbles, typically in a talus slope at the base of a cliff. This includes talus slopes that are cool enough to allow winter ice to remain within the talus through all or part of the summer; these are known as ice caves.

- Terrestrial cave community*

The terrestrial community of a cave with bedrock walls, including the biota of both solution caves (in limestone) and tectonic caves. Temperatures are stable in deep caves. Small or shallow caves may have a temperature gradient ranging from cold (below freezing) to cool (up to 50 degrees F). Although many caves have ice on the cave floor in winter, the ceiling is warm enough for a bat hibernaculum.

* probable association but not confirmed.

Range

New York State Distribution

In New York, Appalachian Bristle Fern has been found in several counties in the Hudson Valley, as well as from Tompkins, Cattaraugus and Chatauqua Counties along the southern tier and central New York.

Global Distribution

Appalachian Bristle Fern is chiefly distributed along the mountain range for which it is named, from Vermont to Alabama, with additional populations in the Ohio River Valley in Illiinois, Indiana, and Kentucky.

Identification Comments

General Description

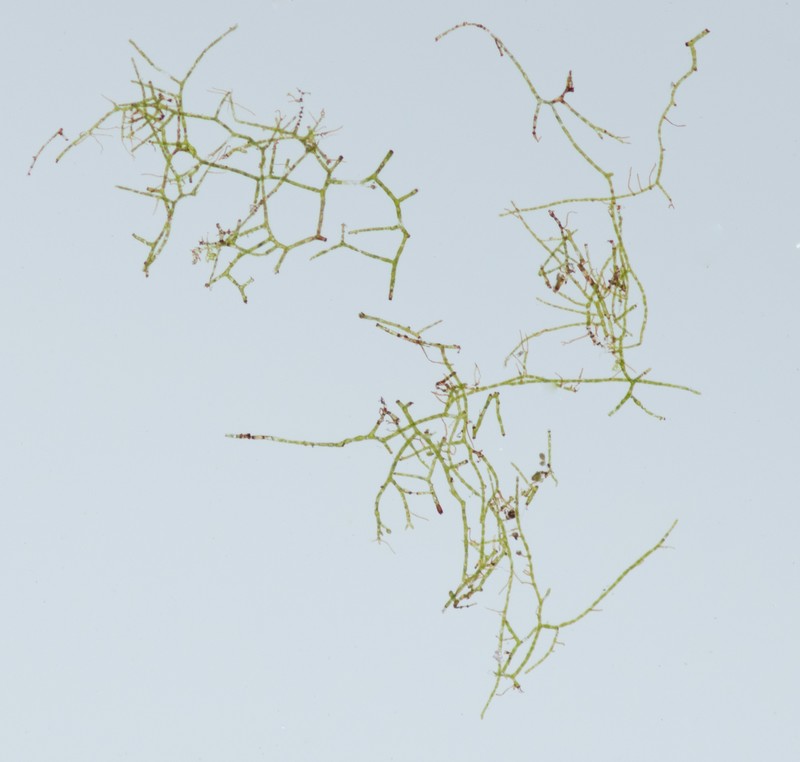

Trichomanes intricatum occurs only as its vegetative form (gametophyte) with sexually reproducing forms (sporophytes) as yet undocumented. The gametophyte is entirely filamentous, much branched, and remains persistent after maturity. Its cup-like cluster of cells (gemmae) are composed of short filaments of undifferentiated cells. Although individual gametophytes may be only a few millimeters thick, they may grow together in moss-like mats up to a square meter in size.

Identifying Characteristics

Trichomanes intricatum occurs only as its vegetative form (gametophyte) with sexually reproducing forms (sporophytes) as yet undocumented. The gametophyte is entirely filamentous, much branched, and remains persistent after maturity. Its cup-like cluster of cells (gemmae) are composed of short filaments of undifferentiated cells. Individual gametophytes are smaller in size than a United State's copper penny.

Best Life Stage for Proper Identification

The vegetative form (gametophyte) is the only life stage known for this species. Examination of a small portion of the plant bearing gemmae cups is needed for positive identification. Due to its rarity this species should not be collected.

Similar Species

This species is only known only from the gametophyte generation, as no sporophytes have ever been documented. It is more likely to be quickly passed over as a moss or liverwort than confused with another fern, and is the only Trichomanes known from New York. The filamentous gametophytes of Trichomanes can be distinguished from algae and from the thread-like chains of cells (protonema) in the haploid phase of mosses by their short cells with numerous disc-shaped chloroplasts, by the presence of short, brown, unicellular rhizoids, and by their production of specialized gemmifer cells and gemmae (FNA 1993).

Best Time to See

The vegetative form (gametophyte) is typically present beginning in early March and persists through November.

- Vegetative

The time of year you would expect to find Weft Fern vegetative in New York.

Weft Fern Images

Taxonomy

Weft Fern

Crepidomanes intricatum (Farrar) Ebihara & Weakley

- Kingdom Plantae

- Phylum Filicinophyta

- Class Filicopsida

(Ferns)

- Order Filicales

- Family Hymenophyllaceae (Filmy-fern Family)

- Order Filicales

- Class Filicopsida

(Ferns)

- Phylum Filicinophyta

Additional Common Names

- Appalachian Bristle Fern

- Appalachian Gametophytes

Synonyms

- Trichomanes intricatum Farrar

Additional Resources

References

Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 1993. Flora of North America, North of Mexico. Volume 2. Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms. Oxford University Press, New York. 475 pp.

Gleason, Henry A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York. 910 pp.

Holmgren, Noel. 1998. The Illustrated Companion to Gleason and Cronquist's Manual. Illustrations of the Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Mitchell, Richard S. and Gordon C. Tucker. 1997. Revised Checklist of New York State Plants. Contributions to a Flora of New York State. Checklist IV. Bulletin No. 490. New York State Museum. Albany, NY. 400 pp.

New York Flora Association. 1990. Preliminary vouchered atlas of New York State flora. New York Flora Association, New York State Museum Institute. 498 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Weldy, T. and D. Werier. 2010. New York flora atlas. [S.M. Landry, K.N. Campbell, and L.D. Mabe (original application development), Florida Center for Community Design and Research http://www.fccdr.usf.edu/. University of South Florida http://www.usf.edu/]. New York Flora Association http://newyork.plantatlas.usf.edu/, Albany, New York

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Elizabeth Spencer

Information for this guide was last updated on: January 31, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Crepidomanes intricatum.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/appalachian-bristle-fern/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.