Ice Cave Talus Community

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Barrens And Woodlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1S2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled in New York - Especially or very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either S1 or S2.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3?

Vulnerable globally (most likely) - Conservation status is uncertain, but most likely at moderate risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 80 or fewer populations or locations in the world, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign a firm conservation status.

Summary

Did you know?

During the spring and summer, the air in ice caves is colder than the outside air. Warm air enters the sinkholes, is cooled as it flows over ice, and then escapes through vents in the slopes, keeping them at a temperature between 37 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit. This creates a variety of microclimates that support species characteristic of cooler climates. For example, the ice caves of the Shawangunks support northern species such as red and black spruce, mountain ash, and creeping snowberry while the surrounding communities are mostly pitch pine barrens and oak forests.

State Ranking Justification

There are about 15 to 40 occurrences statewide. A few documented occurrences have good viability and few are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is limited to areas of the state with fractured talus that accumulate sufficient ice that persists into summer. Although most examples are relatively small, there are a few large, high quality examples in New York. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include mineral extraction and recreational overuse.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of ice cave talus communities in New York have probably declined slightly in recent decades as a result of mineral extraction and other development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of ice cave talus communities in New York have probably declined moderately from historical numbers as a result of mineral extraction and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

This community is dependent on the accumulation of ice and snow deep within fractured talus that persists well into summer, or even year-round. Given this intrinsic vulnerability, ice caves may be susceptible to climate change that results in the elimination of these ice stores. Ice cave talus communities are threatened by adjacent upslope development (e.g., residential, agricultural, industrial) and its associated run-off. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., mining, logging adjacent forests). Recreational overuse in the form of concentrated or sustained rock climbing is a threat to some occurrences. Relatively minor recreational overuse adjacent to cliffs is a lesser threat (e.g., ATVs, trampling by visitors, campgrounds, picnic areas, trash dumping). These threats also have an impact on rare cliff-dwelling plants, such as mountain spleenwort (Asplenium montanum) and several rare bryophytes.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical establish and maintain a natural forested buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they run into the talus cave system. Avoid habitat alteration in the surrounding landscape. Restore sites that have been unnaturally disturbed (e.g., by mining). Although not considered an immediate threat, it may be prudent to prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the ice cave talus community through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as trails and utility ROWs. Monitor rock climbing and caving activity and develop a management plan for sites where recreational overuse is a concern.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

A natural (usually forested) buffer around the ice cave talus community will help it maintain the characteristics that make it unique. It may be desirable to close portions of the cave for various durations in order to protect rare plant habitat.

Inventory Needs

Need quantitative surveys of all sites, especially for bryophytes (rare species have been reported from some occurrences), and search for additional sites. Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of ice cave talus communities. Continue searching for large ice caves in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Determine if climate change will affect ice accumulation and persistance within this community. Research which species are dependent on the ice cave cooling function in order to survive in disjunct, warmer locations.

Rare Species

- Aconitum noveboracense (Northern Monkshood) (guide)

- Adoxa moschatellina (Musk Root) (guide)

- Carex capillaris (Hair-like Sedge) (guide)

- Crepidomanes intricatum (Weft Fern) (guide)

- Draba arabisans (Rock Whitlow Grass) (guide)

- Neotoma magister (Allegheny Woodrat) (guide)

- Vittaria appalachiana (Appalachian Shoestring Fern) (guide)

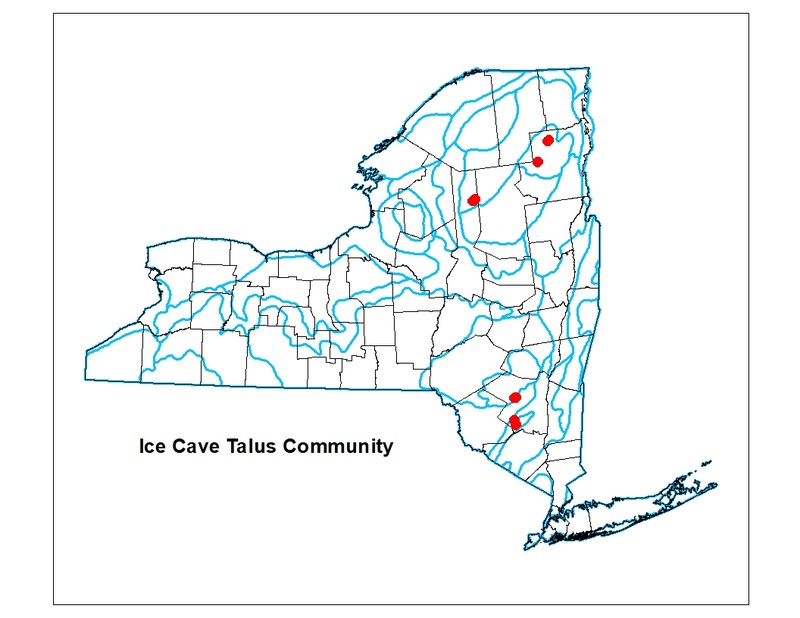

Range

New York State Distribution

Ice cave talus communities are currently known from the Adirondack Mountains, the Shawangunk Mountains, and the Catskill Mountains. Otherwise the range of this community is uncertain. Similar ice caves probably occur elsewhere in New England. "Algific" talus slopes in the midwest may be similar.

Global Distribution

This broadly-defined community may be circumboreal, where substantial amounts of ice accumulate within fractured talus. Examples are suspected to range from northern New England (e.g., Skinner Hollow Cave at Mt. Equinox, VT) and the Adirondack Mountains of New York. Ice caves are also reported from West Virginia (Ice Mountain, WV). Similar cold air producing "algific talus slopes" in the Midwest U.S. may be classified as this community, but need critical comparison of floristic composition.

Best Places to See

- Catskill Park (Ulster County)

- Mckenzie Mountain Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

- Sentinel Range Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

- High Peaks Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

- Fulton Chain Wild Forest, Adirondack Park (Herkimer County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Ice cave talus communities are woodlands that occur at the base of talus slopes that have ice deposited deep within year-round. The cool air emitted from the openings influences the vegetation such that cool-climate northern species are present at sites in the southeastern portion of the state. The canopy features spruces (Picea spp.), birches (Betula spp.), mountain ash (Sorbus americana), and hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). The understory has sparse shrubs and herbs, but often has a well-developed non-vascular layer. Some rare bryophytes have been found in ice cave talus communities.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A woodland community at the base of talus slopes that contain ice deep within. The vegetation is characterized by cool-climate species such as red and black spruce, mountain ash, and creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula). The non-vascular layer is often well-developed.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 1,215 feet and 2,870 feet.

Best Time to See

During July, two species of lowbush blueberry in the understory of this community bear fruit. In autumn, the foliage of the hardwood canopy species and the understory shrubs turn bright colors and provide an attractive contrast to the dark green of the spruces present. Non-vascular species, which are often abundant in ice cave talus communities, can be observed anytime when snow cover is absent.

Ice Cave Talus Community Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Black Spruce / Bog Labrador-Tea - Black Crowberry / Cup Lichen species Talus Scrub (CEGL006268)

- Red Spruce / Skunk Currant Woodland (CEGL006250)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Acadian-Appalachian Subalpine Woodland and Heath-Krummholz (CES201.568)

- Laurentian-Acadian Acidic Cliff and Talus (CES201.569)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Acer pensylvanicum (striped maple)

- Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)

- Betula cordifolia (mountain paper birch)

- Betula papyrifera (paper birch)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

- Picea rubens (red spruce)

- Sorbus americana (American mountain-ash)

- Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer spicatum (mountain maple)

- Kalmia angustifolia var. angustifolia (sheep laurel, sheep-kill)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

- Viburnum lantanoides (hobblebush)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaultheria hispidula (snowberry)

-

Herbs

- Asplenium montanum (mountain spleenwort)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Dryopteris campyloptera (mountain wood fern)

- Dryopteris intermedia (evergreen wood fern, fancy wood fern, common wood fern)

- Lysimachia borealis (starflower)

- Oclemena acuminata (whorled wood-aster)

- Oxalis montana (northern wood sorrel)

- Polypodium virginianum (Virginian rock polypody, Virginian polypody)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Anastrophyllum saxicola

- Bazzania trilobata

- Dicranum spp.

- Hylocomium splendens

- Isopterygium

- Isopterygium spp.

- Mylia taylori

- Ptilium crista-castrensis

- Scapania nemorea

- Sphagnum girgensohnii

Similar Ecological Communities

- Acidic talus slope woodland

(guide)

Acidic talus slope woodlands occur on granite, quartzite, or schist bedrock, and are not influenced by ice deposits. The canopy is dominated by oaks (Quercus spp.), pines (Pinus spp.), and birches.

- Calcareous talus slope woodland

(guide)

Calcareous talus slope woodlands occur on limestone or dolomite bedrock and are not influenced by ice deposits. The canopy is dominated by rich-site indicators, such as sugar maple (Acer saccharum), basswood (Tilia americana), and northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis).

- Shale talus slope woodland

(guide)

Shale talus slope woodlands occur on shale, and are not influenced by ice deposits. The canopy is dominated by oaks, including chestnut oak (Quercus montana), and may include eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) and pignut hickory (Carya glabra).

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Ice Cave Talus Community. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Core, E.L. 1968. The botany of Ice Mountain, West Virginia. Castanea 33: 345-348.

Dirig, Robert. 1994. Lichens of pine barrens, dwarf pine plains, and ice cave habitats in the Shawangunk Mountains, New York. Mycotaxon 52(2):523-558.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Thompson, J.E. 1999. Cliff and talus survey of the Mohonk Preserve. Unpublished report. Daniel Smiley Research Center, New Paltz, NY

Thompson, John. 1996. Vegetation survey of the northern Shawangunk Mountains, Ulster County, New York. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern New York Chapter, Troy, New York.

Van Diver, Bradford B. 1985. Roadside Geology of New York. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, MT.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Gregory J. Edinger

Information for this guide was last updated on: February 5, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Ice cave talus community.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/ice-cave-talus-community/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.