Maritime Holly Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G1G2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled globally - At very high or high risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in the world, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either G1 or G2.

Summary

Did you know?

The old growth maritime holly forest known as Sunken Forest in Fire Island National Seashore is unique among maritime barrier island communities. "It is likely the most northern holly-dominated maritime forest on the Atlantic barrier island chain with the highest holly dominance" (Art 1976). However, because of increasing deer herbivory, particularly on tree seedlings, holly has not been able to grow into the canopy for many years. According to Forrester et al (2006), if heavy browsing continues on this barrier island, the maritime holly forest composition will be further altered by shifting canopy dominance towards a higher percentage of black cherry, one of the most tolerant browse species. This change in species composition will change the characteristic canopy of [this] globally imperiled plant community".

State Ranking Justification

There is one very small, geographically restricted occurrence of this community located in a vulnerable barrier island landscape. Although the occurrence is protected in a National Seashore, the property is heavily used by the public. The trend for the community is slowly declining due to threats that include heavy deer browse and trampling near heavily-used boardwalks.

Short-term Trends

The acreage and extent of this community in New York is suspected to be stable because the one (Sunken Forest) occurrence is well protected and managed, but heavy deer browse and trampling is causing a slow decline in condition.

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of maritime holly forests in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in barrier island processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

While this community is well protected and managed, its barrier island setting is vulnerable to both natural catastrophic events and anthropogenic alteration to natural dune building and erosive processes that could change, reduce, or eliminate it. The primary threats to the community are continued trampling and disturbance adjacent to heavily-used boardwalks and continued heavy deer browse resulting in reduced recruitment of canopy tree seedlings. Shoreline development along the unprotected parts of the Sunken Forest area is reportedly a moderate threat. Recreational impacts from visitor use are a minor threat, including reports of off-road vehicle overuse.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Monitor for disturbance by park visitors. Leave downed wood in place. Consider management to exclude deer from the maritime holly forest, particularly if studies confirm that canopy species recruitment is being affected by heavy browse. Generally, management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees when required to do so.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Any development effort that disrupts connectivity between the open ocean and the maritime dune system should be avoided (e.g., a road running parallel to the beach between the beach and dunes). This community is best protected as part of a large beach, dune, salt marsh complex. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow dynamic ecological processes (overwash, erosion, and migration) to continue. Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities, upland beaches and dunes, and to shallow offshore communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Similarly, fragmentation of linear dune systems should be avoided. Bisecting trails, roads, and developments allow exotic species to invade, potentially increase 'edge species' (such as deer, raccoons, skunks, and foxes), and disrupt physical dune processes.

Inventory Needs

Searches for additional examples of this community on the barrier islands of the South Shore of Long Island, especially on other portions of Fire Island near Sunken Forest, are needed. Areas east of Sunken Forest near Cherry Grove appear to be similar to this community. Faunal data from the Sunken Forest occurrence and a review of Art's (1976) vegetation and soil data is needed.

Research Needs

A critical assessment of the long-term effects of heavy deer browse on this community, particularly addressing canopy species seedling recruitment, is needed.

Rare Species

- Lemna perpusilla (Minute Duckweed) (guide)

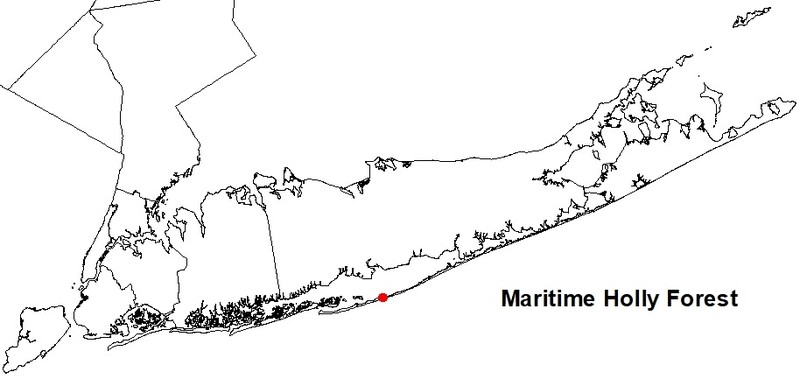

Range

New York State Distribution

Restricted to the southern fringe of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone of New York in Suffolk County and is concentrated on maritime dunes of barrier islands. Known and suspected examples are limited to Fire Island. It is very unlikely to be found elsewhere.

Global Distribution

The community's range extends from Fire Island, New York south to Sandy Hook, New Jersey (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Fire Island National Seashore - Sunken Forest (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A broadleaf evergreen maritime strand forest that occurs in low areas on the back portions of maritime dunes. The dunes protect these areas from overwash and salt spray enough to allow forest formation. In New York State this forest is best developed on and probably restricted to the barrier islands off the south shore of Long Island. The trees are usually stunted and flat-topped because the canopies are pruned by salt spray and exposed to winds; the canopy of a mature stand may be only 16 to 23 ft (5 to 7 m) tall.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The dominant tree is holly (Ilex opaca). Other characteristic trees at lower abundance include sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), post oak (Quercus stellata) and black oak (Quercus velutina). Vines such as Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), common greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), sawbrier (S. glauca), and grape (Vitis spp.) are common in the understory, and they often grow up into the canopy. Shrubs such as highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) are common in the understory, especially at the margins of the forest. Characteristic groundlayer herbs include wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), starry Solomon's seal (Maianthemum stellata), and Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense). There may be small, damp depressions that are somewhat boggy; species found in these depressions include blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), serviceberry, highbush blueberry, and chokeberry (Photinia melanocarpa).

Best Time to See

Visit in the late summer to see the bright red fruits of the holly trees.

Maritime Holly Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- American Holly / Northern Bayberry Forest (CEGL006376)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.302)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Ilex opaca var. opaca (American holly)

- Nyssa sylvatica (black-gum, sour-gum)

- Quercus stellata (post oak)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Ilex opaca

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Amelanchier canadensis var. canadensis (coastal shadbush)

- Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

-

Tree saplings

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Vines

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Smilax rotundifolia (common greenbrier)

-

Herbs

- Aralia nudicaulis (wild sarsaparilla)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Maianthemum stellatum (starry Solomon's-seal)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal oak-holly forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-holly forests are located on well drained silt and sandy loams in low areas on morainal plateaus at higher elevations than maritime communities. They are dominanted by black oak, black gum, red maple (Acer rubrum) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia). Holly is abundant in the subcanopy and tall shrub layers. Maritime holly forests, on the other hand, occur within the zone of maritime wind and salt-spray and are dominated by stunted holly trees with associated species that include sassafras, serviceberry, post oak, and black oak.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Holly Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Art, Henry Warren. 1976. Ecological studies of the Sunken Forest, Fire Island National Seashore, New York. National Park Service. Scientific Monograph Series, no.7. 237 pp.

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Forrester, Jodi A., Donald J. Leopold, and H. Brian Underwood. 2006. Isolating the Effects of White-tailed Deer on the Vegetation Dynamics of a Rare Maritime American Holly Forest. American Midland Naturalist 156(1): 135-150.

Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 140 (4):376-382.

Grossman, D. H., K. Lemon Goodin, and C. L. Reuss, editors. 1994. Rare plant communities of the conterminous United States: An initial survey. The Nature Conservancy. Arlington, VA. 620 pp.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

NatureServe. 2015. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson and K. Metzler. 1996. Community alliances and elements of the eastern region. Second draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Region Conservation Science, Boston, MA. April 11. 234 pp.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson, and J. Lundgren. 1998. International classification of ecological communities: terrestrial vegetation of the northeastern United States. July 1998 working draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science and Natural Heritage ProgramS of the northeastern United States, Boston, MA. July 1998.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime holly forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-holly-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.