Dry Alvar Grassland

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G2?

Imperiled globally (most likely) - Conservation status is uncertain, but most likely at high risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in the world, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign a firm conservation status.

Summary

Did you know?

Alvar is a Swedish term to describe barrens and grassland vegetation growing on thin soils over level outcrops of limestone or dolomite bedrock. This community is limited to areas in Jefferson County underlain with Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex).

State Ranking Justification

There are probably much less than 30 occurrences statewide. A few documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is limited to areas in Jefferson County underlain with Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex), and there are only a few high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land and private conservation land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include conversion to pastureland, development, trampling by visitors, ATVs, and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

It is estimated that dry alvar grassland acreage has declined 10-30% within the last 100 years.

Long-term Trends

The current acreage is estimated to be less than half of the historical acreage.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats are the invasion of exotic plants (in particular pale swallow-wort, buckthorn and honeysuckles), grazing, trampling (especially ORV damage), hydrologic alterations, and development pressure in Jefferson County.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Maintain the mosaic proportional distribution of existing alvar communities by ensuring the the pavement areas and grasslands are kept open. Alvar communities seem to require seasonal flooding, and maintenance of the natural hydrologic regime is critical. Take measures to exclude use of sites by ORVs. Prescribed fire may be a useful tool to promote native plant species diversity (care should be taken in selecting sites for its introduction) and the maintanence of open site conditions (Kost et al. 2007). Develop and implement a prescribed burn plan at appropriate sites. Improve the condition of existing alvar communities by reducing and/or eliminating invasive species, such as black swallow-wort (Cynanchum louiseae), Morrow's honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii), and buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). Identify and target areas with early infestations of invasive exotic plants for control and eradication. Improve the condition of the alvar communities by minimizing trail network and clearly marking existing trails. Improve the landscape context of the barrens by encouraging surrounding landowners to establish natural buffers and restore natural corridors to other larger natural landscape blocks.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Minimize road construction through or bordering these grasslands as their hydrology is very sensitive, easily altered and they are very susceptible to the introduction of invasive exotic plants. Soils are very thin or lacking in and around this community and the effect of clearing and construction on soil retention and erosion must be considered during any development activities. Similarly, these pavements have wide cracks and fissures and any nutrient enrichment (e.g., from septic leach fields and fertilized lawns) may rapidly decrease the water quality of underlying aquifers as well as altering the grassland community structure and function (White 1977).

Inventory Needs

The alvar communities in Jefferson County need to be inventoried and remapped using the current classification of alvar communities: 1) alvar pavement grassland, 2) alvar shrubland, 3) alvar woodland, 4) dry alvar grassland, and 5) wet alvar grassland. Survey for additional occurrences in Jefferson County and the surrounding region to advance documentation and classification of dry alvar grasslands. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to B-ranked). Periodic inventory of the dry alvar grasslands is needed, in order to keep occurrence data current. Quantitative data on composition and variability among patches within occurrences are needed from surveys throughout the growing season. Surveys for rare and characteristic invertebrate species (especially butterflies and moths, along with terrestrial molluscs) are needed for many sites.

Research Needs

Research the composition of dry alvar grasslands in Jefferson County in order to characterize variations and distinguish it from other alvar communities. Studies of the hydrology of alvar communities (a past study was conducted at Chaumont Barrens) and their immediately surrounding landscape are needed to better understand their hydrologic regimes. Continue long-term monitoring of deer browsing and grazing impacts. Establish a monitoring progam at various sites to understand and track the development of impacts from global climate change. Identify areas where fire can be implemented and evaluated as a management tool, including a flora and fauna monitoring component (Reschke et al. 1999).

Rare Species

Range

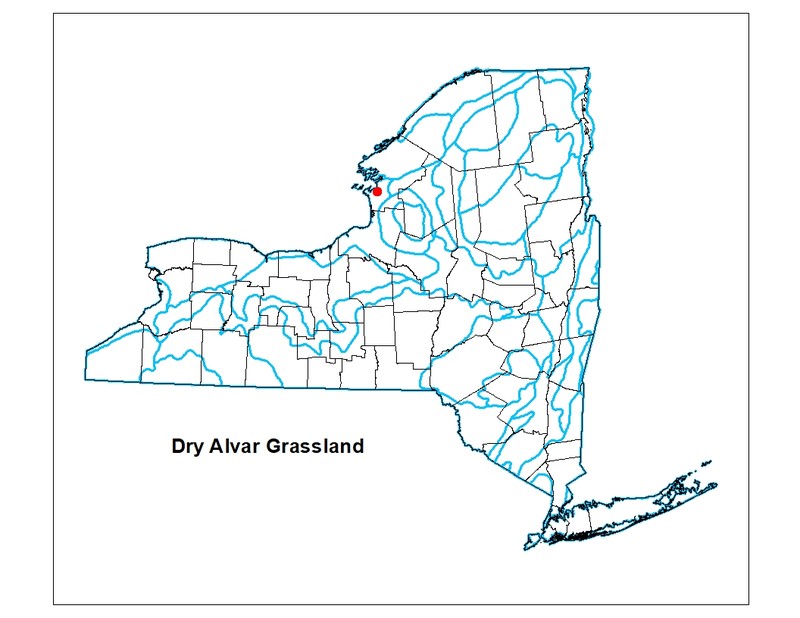

New York State Distribution

Restricted to outcrops of Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex) in Jefferson County. New York's sites are at the easternmost edge of a narrow range extending across southern Ontario to the eastern edge of northern Michigan. There are about 54 square miles (34,368 acres) of Galoo-Rock outcrop complex mapped in Jefferson County in the Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) database for New York.

Global Distribution

The dry alvar grassland type occurs in the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, being found in southern Ontario, northern New York, and northern Michigan (NatureServe Explorer 2015).

Best Places to See

- Limerick Cedars Preserve (Jefferson County)

- Ashland Flats WMA (Jefferson County)

- Chaumont Barrens Preserve (Jefferson County)

Identification Comments

General Description

This community is a grassland community that occurs on very shallow, organic soils that cover limestone or dolostone bedrock. This community has a characteristic soil moisture regime of summer drought in most years. This grassland seems to occur on well-drained soils that are rarely, if ever, saturated or flooded; this interpretation is based on soil texture (soil moisture regime of this type has not been studied). This dry grassland is dominated by poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), and sometimes little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

There is less than 10% cover of trees and less than 25% cover of shrubs. There is usually about 50% cover of herbs and up to about 50% cover of nonvascular plants (mosses, lichens, and algae) growing on exposed limestone or dolostone pavement areas that occur as patches within the grassland. Poverty grass dry alvar grassland usually occurs in small to large patches. Dry alvar grasslands occur on Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 490 feet and 500 feet.

Best Time to See

This community is best seen when the poverty grass (Danthonia spicata) is at its peak in mid to late summer.

Dry Alvar Grassland Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Poverty Oatgrass - Canada Bluegrass - (Little Bluestem) Grassland (CEGL005100)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Great Lakes Alvar (CES201.721)

Characteristic Species

-

Herbs

- Danthonia spicata (poverty grass)

- Phleum pratense ssp. pratense (common Timothy)

- Poa compressa (flat-stemmed blue grass, Canada blue grass)

- Schizachyrium scoparium var. scoparium (little bluestem)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Alvar pavement grassland

(guide)

Alvar pavement grasslands are dominated by a mix of species. Poverty grass (Danthonia spicata) may be present, but is not dominant. Dry alvar grasslands are dominated by poverty grass. Both communities may have flat limestone areas covered with nonvascular plants.

- Alvar shrubland

(guide)

Alvar shrublands have over 25% cover of dwarf, short, and tall shrubs (avg. 43% cover of shrubs). Dry alvar grasslands are dominated by poverty grass (Danthonia spicata) and have less than 25% cover of shrubs.

- Alvar woodland

(guide)

Alvar woodlands have over 25% cover of trees 5 m or taller. Dry alvar grasslands typically lack trees, but a few sparsely scattered trees may grow in the cracks of the limestone pavement.

- Successional northern sandplain grassland

(guide)

While these communities may share similar species, successional northern sandplain grasslands occur on sandy soil and are dominated by bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), hairgrass (Avenella flexuosa), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), and panic grasses (Dichanthelium spp.). Whereas, dry alvar grasslands occur on Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex) and are dominated by poverty grass (Danthonia spicata), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), and sometimes little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium).

- Wet alvar grassland

(guide)

Wet alvar grasslands are dominated by tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia cespitosa), Crawe's sedge (Carex crawei), prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), and flat-stemmed spikerush (Eleocharis elliptica var. elliptica). They occupy the lowest, wettest position in the alvar landscape. Dry alvar grasslands are dominated by poverty grass (Danthonia spicata) and occur in the slightly higher elevation areas in the alvar landscape.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Dry Alvar Grassland. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Gilman, B. 1998. Alvars of New York: a site summary. Finger Lakes Community College. Canadaigua, NY.

NatureServe. 2015. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, C., R. Reid, J. Jones, T. Feeney, and H. Potter. 1999. Conserving Great Lakes Alvars: final technical report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative. The Nature Conservancy, Great Lakes Program, Chicago, IL.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

- Conserving Great Lakes Alvars: final technical report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative (Reschke et al. 1999).

- EPA Great Lakes Ecological Protection and Restoration Conserving Great Lakes Alvars

- NYS DEC Habitat Management Plan for Ashland Flats Wildlife Management Area

- The Nature Conservancy, New York, Chaumont Barrens Preserve

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Gregory J. Edinger

Information for this guide was last updated on: April 10, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Dry alvar grassland.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/dry-alvar-grassland/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.