Inland Salt Pond

- System

- Lacustrine

- Subsystem

- Natural Lakes And Ponds

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G2

Imperiled globally - At high risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in the world, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

Summary

Did you know?

The nickname "The Salt City" was given to Syracuse during the boom time, during the 1700 and 1800s, of the commerical salt industry in the area. During this period, brine from springs including very likely some of the remnant inland salt ponds was one of the local resources used in large scale salt production (Kappel 2000).

State Ranking Justification

This small patch community has been degraded or destroyed throughout its range. The largest examples were likely lost to activities related to salt mining and other industrial development. New York State is at the edge of the range of the community. There are only two currently documented occurrences in New York, and probably not many more historically given that its range is primarily restricted to areas associated with inland salt springs in central New York. There is only one documented occurrence with very good viability in the state (i.e., one AB-ranked occurrence) and it is protected on private conservation land. The current trend of this community is declining moderately as a result of invasive species, agricultural and urban development, and alteration to the natural hydrology.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of inland salt ponds in New York have declined in recent decades as result of habitat destruction (e.g., filling of wetlands) and the spread of invasive species, such as common reed (Phragmites australis).

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of inland salt ponds in New York have probably had a large decline from historical numbers likely correlated to the salt mining industry and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Inland salt ponds are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., agriculture, residential, commercial, roads), habitat alteration (e.g., pollution, dumping, utility ROWs), and recreational overuse (e.g., trampling, fishing?). Alteration to the natural hydrological regime is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, ditching, beaver?). Inland salt marshes are threatened by invasive species, such as reed grass (Phragmites australis) and purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the pond. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the pond and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around ponds, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the pond must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the pond through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities, minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to and from this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as runoff usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the system, they bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algal blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment in which few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider how water moves through the ground, the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Search for historical sites, possibly needs some de novo work. Survey the aquatic community and determine which fish and invertebrates are present.

Research Needs

There is a need for research focusing on identifying and compiling information on previously known and suspected locations of inland salt ponds. Research is also needed to understand both the historical range of variation in water level fluctuations from year to year and how the composition and abundance of characteristic species (including fauna) in the ponds.

Rare Species

- Diplachne fusca ssp. fascicularis (Salt-meadow Grass) (guide)

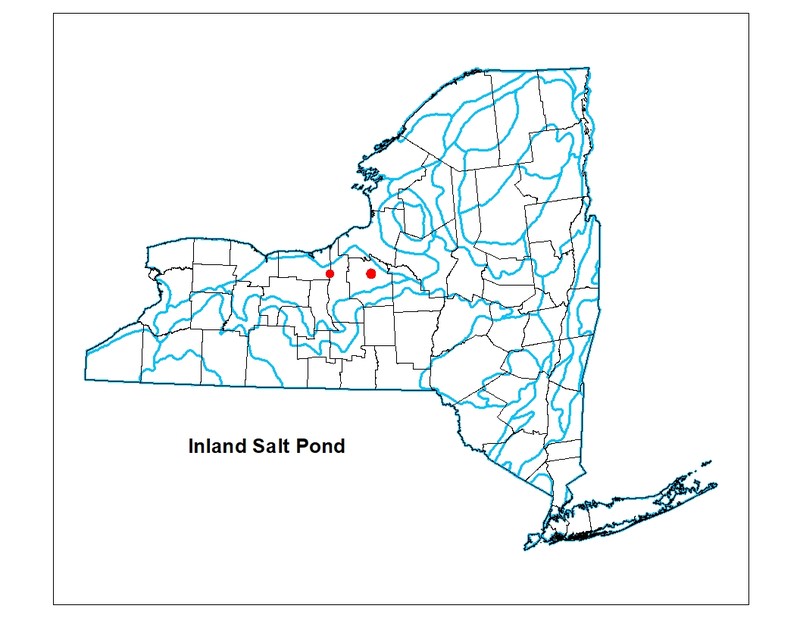

Range

New York State Distribution

Restricted to the Great Lakes plain in Wayne and Onondaga counties, following a narrow zone of salt springs near the northern border of the Finger Lakes. New York is at the eastern edge of range extending to the western Great Lakes plain in the midwest.

Global Distribution

This inland salt pond community type is found in scattered locations in the upper midwestern United States in the Great Lakes region, including Illinois, Michigan, and central New York.

Best Places to See

- Carncross Salt Pond Preserve (Wayne County)

Identification Comments

General Description

This is an aquatic community of a small, spring-fed pond in which the water is salty from flowing through salt beds in the aquifer. These salt springs occur in central New York, and were once common around Onondaga Lake in Syracuse and near Montezuma. Most of the springs have been exploited for the production of salt, and are very disturbed or completely destroyed. The ponds are permanently flooded, but the water levels fluctuate seasonally. The bottom and shores of an inland salt pond are very mucky.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Most examples of this community in New York are severely disturbed. Intact occurrences are dominated by ditch grass (Ruppia maritima) and the floating aquatic Sago pondweed (Stuckenia pectinata).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 370 feet and 380 feet.

Best Time to See

This pond community is observable year round, but walking the shoreline is easier in late summer when the water has drawn down.

Inland Salt Pond Images

Classification

Characteristic Species

-

Submerged aquatics

- Ruppia maritima (widgeon-grass, ditch-grass)

- Stuckenia pectinata (Sago pondweed)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal salt pond

(guide)

While both communities are salty and may be dominated by ditch grass (Ruppia maritima), coastal salt ponds are on the Atlantic Ocean coast, where as inland salt ponds are restricted the salt spring areas of central New York.

- Inland salt marsh

(guide)

Inland salt marshes usually form a fringing border around the permanently flooded inland salt ponds, but not all inland salt marshes have a permanently flooded central pond. Inland salt marshes are more densely vegetated by emergent species, whereas inland salt ponds are dominated by a few aquatic species.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Inland Salt Pond. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Bonham, B.A. 1962. Ecology of a saline spring, Boone's Lick. MA thesis, University of Missouri.

Catling, P. M., and S. M. McKay. 1980. Halophytic plants in southern Ontario. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 94:248-258.

Catling, P.M. and S.M. McKay. 1981. A review of the occurrence of halophytes in the eastern Great Lakes region. Mich. Botanist 20:167-179.

Chapman, Kim Alan, V.L. Dunevitz and H.T. Kuhn. 1985. Vegetational and chemical analysis of a salt marsh in Clinton County, Michigan. The Michigan Botanist. 24:135-144.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Faust, M.E. and N.R. Roberts. 1983. The salt plants of Onondaga Lake, Onondaga County, New York. Bartonia 49:20-26.

Marcus, Bernard A., H.S. Forest and B. Shero. 1984. Establishment of freshwater biota in an inland stream following reduction of salt input. Canadian Field-Naturalist 98(2):198-208.

Muenscher, W.C. 1927. Spartina patens and other saline plants in the Genesee Valley of western New York. Rhodora 29:138-139.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Valentine, Edward and Andrew Zepp. 1986. Carncross Salt Pond monitoring project. Unpublished report.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Gregory J. Edinger

Information for this guide was last updated on: February 5, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Inland salt pond.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/inland-salt-pond/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.