Coastal Salt Pond

- System

- Estuarine

- Subsystem

- Estuarine Intertidal

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

The salinity of coastal salt ponds can change over time. Lakes or ponds are formed when sandspits close off a lagoon or bay of the ocean. During storm surges these sandspits can be destroyed and the pond is again connected to the ocean. The water is typically brackish with varying degrees of salinity depending on the amount of freshwater inflow and if the pond has recently been connected to the ocean salt water. The plant and animal life in these ponds can change drastically depending on the salinity of the water. These ponds can be the nurseries for many species of fish and shellfish. They are also a favorite stopping point for all types of migratory birds.

State Ranking Justification

This community only occurs on the coastal plain of New York. There are very few, small (low acreage) occurrences currently mapped. Many documented occurrences have good viability and are protected while others are threatened by coastal development. The current trend for this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure or alteration to the natural hydrology. This community has declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with an increase in residential and commercial development.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of coastal salt ponds in New York have probably declined in recent decades due to human impacts on the hydrology including ditching, draining, impoundments, and artificial connections to the ocean. The inlets to some of the larger ponds are kept open by dredging to allow boat passage between marinas that were built on the pond and the ocean thereby disrupting the natural processes of the opening and closing of ponds to the ocean.

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of coastal salt ponds have probably declined steadily from their historical range. It is estimated that there were approximately 2000 acres in New York. Currently, a little over 200 acres are mapped. The decline probably coincided with settlement of the area and a steady increase in residential and commercial development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The coastal salt pond community is threatened by coastal development and alterations to hydrology or tidal regimes including ditching, dredging, and the construction of artificial connections to the ocean. The inlets of larger salt ponds are kept open by regular dredging to allow boat traffic. The natural opening and closing of the connection to the ocean caused by storms is disrupted. Shorelines are also artificially hardened to prevent the natural movement of sand. There are also threats to water quality including oil spills from holding tanks on adjacent uplands. Other threats include an increase in recreational development, trash, the presence of exotic species including mute swans, and the spread of invasive plant species such as common reed (Phragmites australis).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Coastal plain ponds are susceptible to alterations by a number of different factors. Management considerations of these ponds on Long Island needs to include: preventing off-road vehicle use and limiting trails; improving the integrity of the pond margins; maintaining or improving water quality; removing invasive species including mute swans and common reed (Phragmites australis); maintaining intact upland landscapes and maintaining the natural hydrology including avoiding mosquito ditching and artificial connections to the ocean.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize or eliminate alterations to hydrology. In particular, strive to maintain the natural processes that originally formed the ponds. These ponds were formed and are maintained when sandspits close off a lagoon or bay of the ocean forming a pond or lake. During storm surges, these sandspits can be destroyed and the pond is once again connected to the ocean. The artificial dredging to maintain a permanent connection to the ocean disrupts this process. In addition, hardened (stabilized) shorelines prevent the natural movement of sand by wind and water that is instrumental in the formation and maintenance of this natural community. Connectivity to other coastal natural communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Development of site conservation plans that identify threats and their sources and provide management and protection recommendations would ensure the long-term viability of coastal salt ponds.

Inventory Needs

Inventory needs for coastal salt ponds include: conduct surveys for additional sites; improve maps; refine species identifications; improve composition and structure descriptions for each association; and determine long-term variation of tidal overwash rate, salinity, temperature, water surface elevation, and trophic state.

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about coastal salt ponds, especially to advance our understanding of their classification. Research is also needed to document the two community microhabitats that are typically encountered within one pond complex: 1) the "pond" or aquatic portion of the complex and 2) the "shore" or the non-aquatic part of the complex. These two microhabitats are likely to warrant separate communities and may be distinguished in a future version of the state community classification: the former retaining the name "coastal salt pond," the latter designated as a "coastal salt pond shore."

Rare Species

- Bolboschoenus maritimus ssp. paludosus (American Saltmarsh Bulrush) (guide)

- Charadrius melodus (Piping Plover) (guide)

- Diplachne fusca ssp. fascicularis (Salt-meadow Grass) (guide)

- Eleocharis quadrangulata (Square-stemmed Spike Rush) (guide)

- Ischnura ramburii (Rambur's Forktail) (guide)

- Kinosternon subrubrum (Eastern Mud Turtle) (guide)

- Oxybasis rubra var. rubra (Red Pigweed) (guide)

- Potentilla anserina ssp. pacifica (Coastal Silverweed) (guide)

- Rumex fueginus (American Golden Dock) (guide)

- Sesuvium maritimum (Sea Purslane) (guide)

- Symphyotrichum subulatum var. subulatum (Annual Saltmarsh Aster) (guide)

Range

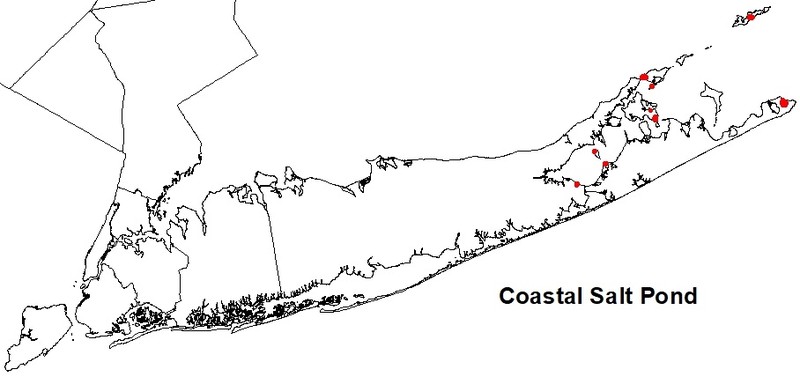

New York State Distribution

Coastal salt ponds are limited to the coastal plain (lowlands) of New York. Their original range probably included all of Long Island. Currently, most are found in eastern Suffolk County.

Global Distribution

This coastal salt pond community occurs along the northeastern Atlantic coast from Maine to New Jersey and possibly to Maryland and Virginia. New York is in the central part of their range (NatureServe Explorer 2009).

Best Places to See

- Montauk Point State Park (Suffolk County)

- Orient Beach State Park (Suffolk County)

- Cow Neck SCFWH (Suffolk County)

- Fishers Island Beaches SCFWH (Suffolk County)

- Robins Island SCFWH (Suffolk County)

- Mashomack Preserve (Suffolk County)

- Oyster Pond SCFWH (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

This community occurs along the marine shoreline. Lakes or ponds are formed when sandspits close off a lagoon or bay of the ocean. During storm surges these sandspits can be destroyed and the pond is again connected to the ocean. The water is typically brackish with varying degrees of salinity depending on the amount of freshwater inflow and if the pond has recently been connected to the ocean salt water. The ponds have two microhabitats, the pond itself and the shoreline. Dominant plants and animals can change quickly depending on salinity. Typical ponds are dominated by widgeon grass and the marine red algae tubed weed. Animals in these ponds include multiple species of grass shrimp and the estuarine minnow mummichog, sheepshead minnow and various killifish. Common coastal waterbirds include great blue herons and egrets.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This community occurs along the marine shoreline. The salt ponds are formed when sandspits close off a lagoon or bay of the ocean. During storm surges these sandspits can be destroyed and the pond is again connected to the ocean. A narrow beach usually separates the pond from the ocean.

Best Time to See

For the naturalist, some of the best times to visit are during spring and fall bird migrations. Many species of birds use the ponds as stopover points along their journeys from wintering sites in the south to breeding grounds further north. If the salt pond is big enough, the shallow and warmer waters make for good kayaking and other recreational activities in the summer months.

Coastal Salt Pond Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Common Threesquare - Dwarf Spikerush Salt Marsh (CEGL006398)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Atlantic Coastal Plain Northern Salt Pond Marsh (CES203.892)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Baccharis halimifolia (groundsel-tree)

- Iva frutescens (salt marsh-elder)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Baccharis halimifolia (groundsel-tree)

-

Herbs

- Chenopodium spp.

- Distichlis spicata (salt grass)

- Eleocharis acicularis (needle spike-rush)

- Eleocharis parvula (salt-loving spike-rush)

- Hibiscus moscheutos ssp. moscheutos (swamp rose-mallow)

- Panicum virgatum (switch grass)

- Phragmites australis (old world reed grass, old world phragmites)

- Pluchea odorata (salt marsh-fleabane)

- Ptilimnium capillaceum (mock bishopweed)

- Schoenoplectus americanus (chair-maker's bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus pungens var. pungens (three-square bulrush)

- Spartina alterniflora (smooth cord grass)

- Spartina patens (salt-meadow cord grass)

-

Nonvascular plants

- marine green algae (Cladophora spp.)

- marine red algae (Polysiphonia spp.)

-

Floating-leaved aquatics

- Potamogeton perfoliatus (clasping-leaved pondweed)

- Stuckenia pectinata (Sago pondweed)

-

Submerged aquatics

- Ruppia maritima (widgeon-grass, ditch-grass)

- Zannichellia palustris (horned pondweed)

-

Unvegetated

- grass shrimp (Palaemonetes spp.),

- mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus),

- sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus)

- silversides (Menidia spp.)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Brackish interdunal swales

(guide)

While both communities form behind sand dunes and experience tidal flooding, brackish interdunal swales are usually linear features dominated by graminoids, whereas coastal salt ponds have an open water component dominated by widgeon-grass (Ruppia maritima) and/or marine macroalgae.

- Coastal plain pond

(guide)

This is a permanent, freshwater pond with a widely fluctuating water table and not associated with the ocean. The pond may have abundant floating, emergent, and submerged aquatic vegetation including bladderworts and waterlilies. These ponds differ from coastal salt ponds because they contain freshwater and have widely fluctuating water levels on a yearly basis.

- Coastal plain pond shore

(guide)

Coastal plain pond shores are found exclusively in the coastal plain of Long Island in New York state. The community occupies the gentle slopes of freshwater ponds formed in the glacial till. When water levels are low, distinctive zones or rings of herbaceous vegetation form around the pond.

- High salt marsh

(guide)

The shoreline fringe of a coastal salt pond may develop a narrow band of high salt marsh. If the pond outlet remains open for decades or more tidal salt marsh may become more extensive in the pond area.

- Impounded marsh

A freshwater community that was created and maintained by human activities in which the water levels have been artificially manipulated or modified, often for the purpose of improving waterfowl habitat. Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) may become dominant within this cultural community. Impounded marshes are fresh water and artificially manipulated. They are not generally associated with saline environments.

- Salt panne

(guide)

While both communities may have widgeon-grass (Ruppia maritima) growing in the open water portion of the community, salt pannes typically form within large areas of high salt marsh, whereas coastal salt ponds form behind dunes with a small inlet that may fill with sand and occasionally close.

- Saltwater tidal creek

(guide)

While both commununities have a saline or brackish open water component often dominated by widgeon-grass (Ruppia maritima), saltwater tidal creeks are linear features with a permanent tidal connection to the ocean or bay, whereas coastal salt ponds form behind dunes with a small inlet that may fill with sand and occasionally close.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Coastal Salt Pond. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Bliven, S. and A.L. Hankin (eds). 1985, Salt ponds and tidal inlets: maintenance and management considerations. Proceedings of a conference, November 19, 1983. Sponsored by Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management Office, Lloyd Center for Environmental Studies. Lloyd Center Publication # 2-85.

Conard, H.S. 1935. The plant associations of central Long Island. American Midland Naturalist 16:433-515.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Harlin, M.M., V.J. Masson, and R.E. Flores. 1995. Distribution and abundance of submerged aquatic vegetation in Trustom Pond, Rhode Island. Report submitted to US Fish and Wildlife Service, October 13, 1995.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated October, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Salt Ponds Coalition. 2009. Salt Ponds Coalition [web application]: Available http://www.saltpondscoalition.org/ May 2021.

Thorne-Miller, B., M. M. Harlin, G. B. Thursby, M. M. Brady-Campbell, and B. A. Dworetsky. 1983. Variations in the distribution and biomass of submerged macrophytes in five coastal lagoons in Rhode Island, USA. Botanica Marina 26:231-242.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coastal salt pond.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/coastal-salt-pond/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.