Meromictic Lake

- System

- Lacustrine

- Subsystem

- Natural Lakes And Ponds

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1S2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled in New York - Especially or very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either S1 or S2.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

The best-known example of meromictic lake in New York is Green Lake in the town of Fayetteville. Green Lake got its name from its unusual green color from high levels of calcium carbonate, and not phytoplankton or algae that often give lakes a green appearance when their populations are high. Calcium carbonate reflects the green wavelength, thus giving Green Lake its distinctive green color (NYS DEC).

State Ranking Justification

There are probably less than 20 occurrences statewide, and the total acreage is relatively small compared to other more common lake types. About three documented occurrences have good viability and are protected on public land. This community is limited to areas of the state where glacial waterfalls scoured deep plungepools into the bedrock creating steep-sloped margins that prevent winds from mixing the water. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on protected land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to development in the surrounding landscape and recreational overuse.

Short-term Trends

The number and acres of meromictic lakes in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of local lake protection efforts and state wetland protection regulations.

Long-term Trends

The number and acres of meromictic lakes in New York are probably comparable to historical numbers.

Conservation and Management

Conservation Overview

Where practical, establish and maintain a lakeshore buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the lake. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the lake and surrounding landscape. For example, roads should not be routed through the lakeshore buffer area. If a lake must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling and culverts. Restore lakes that have been affected by unnatural disturbance (e.g., remove obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology). Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the lake through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors.

Threats

The greatest threat would be altering hydrology or mixing status, but these lakes have so few species and such harsh conditions that they are unlikely to be altered or used very much. Run-off from development and/or clearing in the immediate lake watershed may be a threat. High visitor use of lake perimeter trails is a lesser threat.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Consider how water flows around and into this lake community. Projects that occur near this community must consider the proximity of the development to this lake and the potential for changing how water flows, both above ground and below ground, into this waterbody. Impervious surfaces that rapidly divert water to the pond should be avoided. For lakes with perimeter trails consider reducing trail width, evaluating current uses, and stabilizing heavy impact areas along the trail with native materials to prevent runoff and erosion into the lake. Prevent the spread of non-native species into or around the lakes. Identify the potential impacts of beach use, if present along the the lakeshore.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities, minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this lake community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the lake, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this lake type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in lakes cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Regularly inventory known occurrences of meromictic lakes to document characteristic biota and abiotic condition (e.g., once every 5-10 years). Inventory leads for meromictic lakes reported in the literature, including the following: Saratoga County (Ballston Lake South Basin), Hamilton County (Clear Pond), Ontario County (Grossman's Pond), and Monroe County (Ides Cove in Irondequoit Bay).

Research Needs

Portions of large lakes and bays, such as Cayuga Lake, Seneca Lake, and Irondequoit Bay, are reported to be meromictic (Anderson et al. 1985, Bubeck et al. 1995). Research is needed to determine if these areas should be classified as meromictic lakes, or treated as an embedded feature of a large lake type (e.g., summer-stratified monomictic lake). The distinction between meromictic lake and bog lake needs to be more critically evaluated, because occasionally bog lakes can also become meromictic or chemically stratified.

Rare Species

- Gavia immer (Common Loon) (guide)

Range

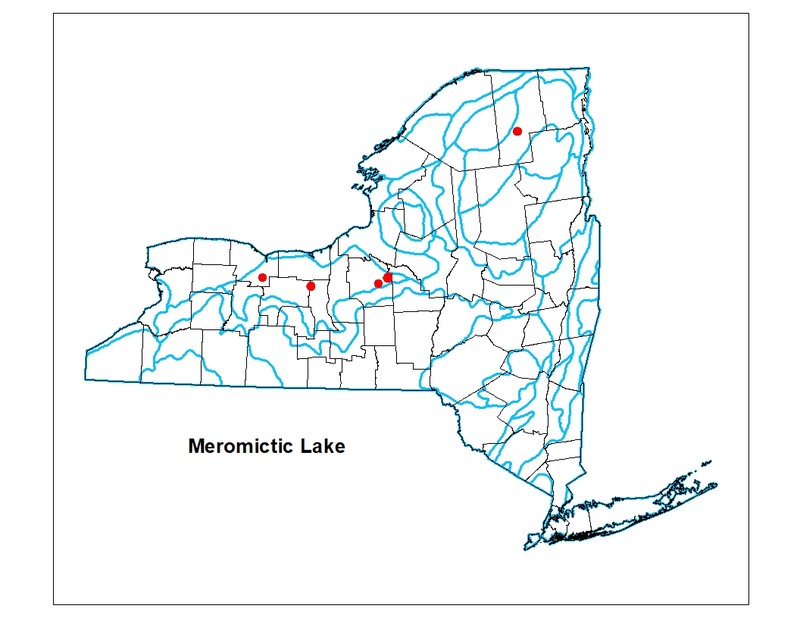

New York State Distribution

Currently documented occurrences are in Onondaga, Franklin, and Seneca counties. Unconfirmed leads include the following: Saratoga County (Ballston Lake), Hamilton County (Clear Pond), Ontario County (Grossman's Pond), and Monroe County (Ides Cove in Irondequoit Bay and Devil's Bathtub in Mendon Ponds County Park).

Global Distribution

This broadly-defined community may be worldwide. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are suspected to span north to southern Canada, east to New Hampshire and Maine, west to Minnesota, southwest to Indiana and Kentucky, and southeast to Pennsylvania (Anderson et al. 1985).

Best Places to See

- Green Lakes State Park (Green Lake and Round Lake) (Onondaga County)

- Clarks Reservation State Park (Glacier Lake) (Onondaga County)

- Mendon Ponds County Park (Devils Bathtub) (Monroe County)

- Potters Pond (Franklin County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Meromictic lakes are relatively deep with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Meromictic lakes must remain permanently chemically stratified (i.e., have a chemocline) throughout the year. The chemical stratification is usually, but not necessarily, correlated with low dissolved oxygen at the bottom. Additionally, these lakes are usually protected from mixing by their large depths relative to surface area and/or their sheltered landscapes or adjacent tree cover. Chemical stratification may be interpreted broadly, but is apparently most often measured by salinity gradients or total cation and anion concentrations.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 418 feet and 1,670 feet.

Best Time to See

Merotmictic lakes are scenic year-round, but the characteristic green color is most evident during ice-free months.

Meromictic Lake Images

Classification

Characteristic Species

-

Nonvascular plants

- Chara spp.

-

Submerged aquatics

- Elodea spp.

- Potamogeton spp.

-

Unvegetated

- Ameiurus nebulosus

- Asterionella sp.

- Catostomus commersoni

- Ceratium hirundinella

- Ceriodaphnia sp.

- Coccochloris sp.

- Diaphanasoma brachyurum

- Dinobryon sp.

- Lamprocystis roseopersicina

- Mougeotia sp.

- Navicula sp.

- Oedogonium sp.

- Oscillatoria sp.

- Perca flavescens

- Peridinium spp.

- Spirogyra sp.

- Synedra sp.

- Synura sp.

Similar Ecological Communities

- Bog lake/pond

(guide)

Bog lake/pond: The aquatic community of a dystrophic lake (an acidic lake with brownish water that contains a high amount of organic matter) that typically occurs in a small, shallow basin (e.g., a kettehole) that is protected from wind and is poorly drained. These lakes occur in areas with non-calcareous bedrock or glacial till; many are fringed or surrounded by a floating mat of vegetation (in New York usually either bog or poor fen). Characteristic features of a dystrophic lake include the following: murky water that is stained brown, with low transparency; water that is low in plant nutrients (especially low in calcium), with naturally low pH (less than 5.4); and the lake may have oxygen deficiencies in deeper water (the profundal zone). The lack of calcium blocks bacterial action, reducing the rate of decay of organic matter with subsequent accumulation of peat or muck sediments. Colloidal and dissolved humus material reduces transparency and increases acidity of the water. Characteristic macrophytes include water-shield (Brasenia schreberi), fragrant white water lily (Nymphaea odorata), yellow pond-lily (Nuphar microphylla, and Nuphar variegata), bladderworts (Utricularia vulgaris, U. geminiscapa, U. purpurea), pondweeds (Potamogeton epihydrus, P. oakesianus), bur-reeds (Sparganium fluctuans, S. angustifolium), and clubrush (Scirpus subterminalis). Characteristic zooplankton may include the rotifers Keratella spp. and Brachionus spp. Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Eutrophic dimictic lake

(guide)

Eutrophic dimictic lake: The aquatic community of a nutrient-rich lake that occurs in a broad, shallow basin. These lakes are dimictic: they have two periods of mixing or turnover (spring and fall); they are thermally stratified in the summer, and they freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter. Aquatic macrophytes are abundant in shallow water, and there are many species present, but species diversity is generally lower than in mesotrophic lakes. Characteristic plants include tapegrass (Vallisneria americana), pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.), bur-reeds (Sparganium spp.), and the floating aquatic plants white water-lily (Nymphaea spp.), yellow pond-lily (Nuphar luteum), and water-shield (Brasenia schreberi). Characteristic features of a eutrophic lake include the following: yellow, green, or brownish-green water that is murky, with low transparency (Secchi disk depths typically less than 2.5 m, but up to 4 m in some cases); water rich in plant nutrients (especially high in phosphorus, nitrogen and calcium); high primary productivity (inorganic carbon fixed = 75 to 250 g/m2/yr); lake sediments that are rich in organic matter (usually consisting of a fine organic silt or copropel); water that is well-oxygenated above the summer thermocline, but oxygen-depleted below the summer thermocline or under ice; epilimnion volume that is relatively large compared with hypolimnion; and a weedy shoreline. Alkalinity is typically high (greater than 12.5 mg/l calcium carbonate). Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Eutrophic pond

(guide)

Eutrophic pond: The aquatic community of a small, shallow, nutrient-rich pond. Species diversity is typically high. Aquatic vegetation is abundant. Characteristic plants include coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), duckweeds (Lemna minor, L. trisulca), waterweed (Elodea canadensis), pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.), water starwort (Heteranthera dubia), bladderworts (Utricularia spp.), naiad (Najas flexilis), tapegrass or wild celery (Vallisneria americana), algae (Cladophora spp.), common yellow pond-lily (Nuphar variegata), and white water-lily (Nymphaea odorata). The water is usually green with algae, and the bottom is mucky. Eutrophic ponds are too shallow to remain thermally stratified throughout the summer; they often freeze and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface), therefore they are winter-stratified monomictic ponds. Additional characteristic features of a eutrophic pond include the following: water that is murky, with low transparency (Secchi disk depths typically less than 4 m); water rich in plant nutrients (especially high in phosphorus, nitrogen, and calcium), high primary productivity (inorganic carbon fixed = 75 to 250 g/m2/yr) and a weedy shoreline. Alkalinity is typically high (greater than 12.5 mg/l calcium carbonate). Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Marl pond

(guide)

The lake types are similar in that they are glacially-formed kettlehole waterbodies and can share similar phytoplankton and non vascular plants, such as stoneworts (Chara sp.). Marl ponds usually draw down in most years revealing a vegetated marl pond shore with calcium carbonate precipate (marl) on the benthic surface; meromictic lakes may have some marl, but are much deeper and usually do not drawdown in most years. Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Mesotrophic dimictic lake

(guide)

Mesotrophic dimictic lake: The aquatic community of a lake that is intermediate between an oligotrophic lake and a eutrophic lake. These lakes are dimictic: they have two periods of mixing or turnover (spring and fall), they are thermally stratified in the summer (warmest water at the surface), and they freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface). These lakes typically have a diverse mixture of submerged macrophytes, such as several species of pondweeds (Potamogeton amplifolius, P. praelongus, P. robbinsii), water celery or tape grass (Vallisneria americana), and bladderworts (Utricularia spp.). Characteristic features of a mesotrophic lake include the following: water with medium transparency (Secchi disk depths of 2 to 4 m); water with moderate amounts of plant nutrients; moderate primary productivity (inorganic carbon fixed = 25 to 75 g/m2/yr); lake sediments with moderate amounts of organic matter; and moderately well-oxygenated water. Alkalinity is typically moderate (slightly greater than 12.5 mg/l calcium carbonate). Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Oligotrophic dimictic lake

(guide)

Oligotrophic dimictic lake: The aquatic community of a nutrient-poor lake that often occurs in deep, steeply-banked basins. These lakes are dimictic, meaning they have two periods of mixing and turnover (spring and fall); they are stratified in the summer, then they freeze in winter and become inversely stratified. Common physical characteristics of oligotrophic lakes include blue or green highly transparent water (Secchi disk depths from 4 to 8 m), low dissolved nutrients (especially nitrogen and calcium), low primary productivity, and sediment with low levels of organic matter. Additionally, the lakes have an epilimnion volume that is low relative to the hypolimnion, high dissolved oxygen levels year-round through all strata, and low alkalinity. The plant community is primarily in the shallow parts of the lake, between 1 and 3 m (3 to 10 feet), and is dominated by rosette-leaved aquatic species. Characteristic species include seven-angle pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum), water lobelia (Lobelia dortmanna), quillworts (Isoetes echinospora ssp. muricata, I. lacustris), milfoils (Myriophyllum alterniflorum, M. tenellum), bladderworts (Utricularia purpuea, U. resupinata), tape grass (Vallisneria americana), and creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens). Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Oligotrophic pond

(guide)

Oligotrophic pond: The aquatic community of a small, shallow, nutrient-poor pond. The water is very clear, and the bottom is usually sandy or rocky. Aquatic vegetation is typically sparse, and species diversity is low. Characteristic species are rosette-leaved aquatics such as pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum), water lobelia (Lobelia dortmanna), and quillwort (Isoetes echinospora). Oligotrophic ponds are too shallow to remain thermally stratified throughout the summer; they often freeze and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface), therefore they are winter-stratified monomictic ponds. Additional characteristic features of an oligotrophic pond include the following: blue or green water with high transparency (Secchi disk depths of 4 to 8 m); water low in plant nutrients (especially low in nitrogen, also low in calcium); low primary productivity (inorganic carbon fixed = 7 to 25 g/m2/yr). Alkalinity is typically low (less than 12.5 mg/l calcium carbonate). Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Summer-stratified monomictic lake

(guide)

Summer-stratified monomictic lakes are so deep (or large) that they have only one period of mixing or turnover each year (monomictic), and one period of stratification. These lakes generally do not freeze over in winter (except in unusually cold years), or form only a thin or sporadic ice cover during the coldest parts of midwinter, so the water circulates and is isothermal during the winter (similar temperature though the water column). These lakes are typically thermally stratified only in the summer (warmest water at the surface); they are oligotrophic to mesotrophic and alkaline. Characteristic aquatic macrophytes include pondweeds (Potamogeton gramineus, P. richardsonii, P. pectinatus), horned pondweed (Zannichellia palustris), naiad (Najas flexilis), waterweed (Elodea canadensis), tapegrass or wild celery (Vallisneria americana), and coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum). Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

- Winter-stratified monomictic lake

(guide)

Winter-stratified monomictic lakes have only one period of mixing each year because they are very shallow in relation to its size and is completely exposed to winds. These lakes continue to circulate throughout the summer and typically never become thermally stratified in that season. They are only stratified in the winter when they freeze over and become inversely stratified (coldest water at the surface). They are eutrophic to mesotrophic. Littoral, and epilimnion species assemblages predominate. Pelagic species assemblages are well developed. Vascular plants are typically diverse. Characteristic aquatic macrophytes include water stargrass (Heteranthera dubia), coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), waterweed (Elodea spp.), naiad (Najas flexilis), tapegrass (Vallisneria americana), and pondweeds (Potamogeton perfoliatus, P. pectinatus, P. pusillus, P. richardsonii, P. nodosus, P. zosteriformis). The macroalgae Chara may be abundant. Meromictic lake: the aquatic community of a relatively deep lake with small surface area that is so protected from wind-stirring that it has no annual periods of complete mixing, and remains chemically stratified throughout the year. These lakes may be protected from mixing by a sheltered surrounding landscape (e.g., a deep basin) or by adjacent tree cover. Meromictic lakes in New York freeze over and become inversely stratified in the winter (coldest water at the surface); they pass through spring, and fall periods of isothermy without circulating. Meromictic lakes frequently have dichothermic stratification, meaning that the minimum temperature occurs in the middle stratum. The stagnant waters in the lower part of a meromictic lake become heavily loaded with dissolved salts, and lack oxygen. Chemical stratification is most often measured by salinity gradients, or total cation and anion concentrations. Gradients may be present for chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, phosphorus, or iron. Flushing rates are typically low. Some examples of this lake type may be dystrophic, and thus resemble bog lakes. Species diversity is low because very few organisms can tolerate the extreme chemical conditions of the lower strata of a meromictic lake. Fishes are absent or sparse.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Meromictic Lake. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Anderson, Roger Y., Walter E. Dean, J. Platt Bradbury, and David Love. 1985. Meromictic Lakes and Varved Lake Sediments in North America. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1607.

Berg, C.O. 1963. Middle Atlantic states. Chapter 6 from Limnology in North America. The University of Wisc. Press.

Bohannan, Brooke. 1994. Physical and chemical analysis of Potters Pond. Limnology report. Adirondack Aquatic Institute. Paul Smith's College. Paul Smith's, New York.

Diment, W.H. 1969. A limnological reconnaissance of Devil's Bathtub, a meromictic lake in western New York. Part I: Physics and Geology [abs]: EOS (American Geophysical Union), v. 50, p. 194.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Eggleton, Frank E. 1956. Limnology of a meromictic, interglacial plunge-basin lake. Trans. American Miscroscop. Society 75:334-378.

Fry, Brian. 1986. Sources of carbon and sulfur nutrition for consumers in three meromictic lakes of New York State. Limnol. Oceanogr. 31(1): 79-88.

Howard, H.H. 1968. Phytoplankton studies of Adirondack Mountain Lakes. American Midland Naturalist 80(2): 413-427.

Mosher, Elizabeth A. 2016. Macroinvertebrate assemblage inteh littoral zone of Green Lake, Fayetteville, NY; in comparison with three nearby lakes. Honors Theses. SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Nichols, W. F. 2015. Natural Freshwater Lakes and Ponds in New Hampshire: Draft Classification. NH Natural Heritage Bureau, Concord, NH.

Olivero-Sheldon, A. and M.G. Anderson. 2016. Northeast Lake and Pond Classification. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science, Eastern Regional Office. Boston, MA.

Pendl, M.P. and K.M Stewart. 1986. Variations in carbon fractions within a dimictic and meromictic basin of the Junius Ponds, New York. Freshwater Biology 16: 539-555.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Stewart, K.M. 1969. A limnological reconnaissance of Devil's Bathtub, a meromictic lake in western New York. Part II: Chemistry and Biology [abs]: EOS (American Geophysical Union), v. 50, p. 194.

Thompson, J.B., F.G. Ferris, and D.A. Smith. 1990. Geomicrobiology and sedimentology of the micolimnion and chemocline in Fayetteville Green Lake, New York. PALAIOS 15 (1): 52-75.

Toney, Jaime L., Donald T. Rodbell, and Norton G. Miller. 2003. Sedimentologic and palynologic records of the last deglaciation and Holocene from Ballston Lake, Nre York. Quaternary Research 60:189-199.

Links

- Adirondack Lakes Survey Corporation

- Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program (APIPP) Aquatic Program Early Detection Reports

- Clark Reservation State Park

- Green Lake (NYS DEC)

- Green Lakes State Park

- Lakes and Rivers (NYS DEC)

- Mendon Ponds Park (Monroe County)

- New York State Federation of Lake Associations (NYSFOLA) Aquatic Invasive Species by County

- Northeast Lake and Pond Classification System (TNC)

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Gregory J. Edinger

Information for this guide was last updated on: March 26, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Meromictic lake.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/meromictic-lake/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.