Alpine Sliding Fen

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Peatlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1S2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled in New York - Especially or very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either S1 or S2.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Sliding fens presumably become supersaturated from major rain events and slide off the cliff before peat build-up resumes. Water is derived from runoff and seeps at higher elevation. Reportedly the peat will accumulate until a critical mass is built up and the large areas of the peat mat slide to the bottom of the steep slope, a phenomenon that may occur once about every 500 years. Alpine sliding fens are limited to the highest elevation areas of the state above the timberline (about 3,500 feet).

State Ranking Justification

There are probably less than 10 occurrences of alpine sliding fen statewide totaling less than 30 acres. Alpine sliding fens are limited to the highest elevation areas of the state above the timberline (about 3,500 feet). Alpine sliding fen vegetation is fragile and threatened by visitors trampling it. Although all occurrences are protected on state land, all are threatened by the combined effects of recreational overuse, atmospheric deposition, and possibly climate change.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of alpine sliding fens in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of conservation efforts at high elevation areas in the state.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of alpine sliding fens in New York have probably declined slightly from historical numbers likely correlated with minor development and recreational overuse on some summits.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Alpine sliding fen vegetation is fragile because it grows on a shallow peat mat on very steep, open slopes that are prone to breaking and sliding, thus the primary threat to alpine sliding fens is recreational overuse that involves the trampling of fragile peatland vegetation. Communities that occur at higher elevations in the state (e.g., >3,000 feet) may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of atmospheric deposition and climate change, especially acid rain and temperature increase. Unprotected examples of alpine sliding fen may be threatened by development and recreational overuse (e.g., hiking trails, ski slopes and its related infrastructure).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Continue restoration efforts for severely trampled sites. Management activities should be consistent with recommendations presented in the High Peaks Wilderness Unit Management Plan (NYS DEC 1999).

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Any nearby development, including trail building, should strive to minimize across-slope and down-slope erosion, especially activities that cut down to the bedrock potentially destabilizing patches of fen. Development should also consider hydrologic connectivity and sub-surface water flow. Activities that alter water flowing towards sliding fens may also alter the character and quality of the fen.

Inventory Needs

A statewide review of alpine and high elevation (>3,000 feet) communities is desirable. Need quantitative data and monitoring plots within alpine sliding fens; need more work on lichens, bryophytes, and characteristic fauna. Inventory sites with reports of alpine sliding fen (e.g., Whiteface Mountain East, Whiteface Mountain West, Macomb Mountain, Mount Colden, and Gothics).

Research Needs

Research the long-term combined effects that atmospheric deposition and climate change may have on alpine sliding fen occurrences. Compare alpine sliding fens in New York with types described in NH and VT (e.g., Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Document the periodicity of the sliding process.

Rare Species

Range

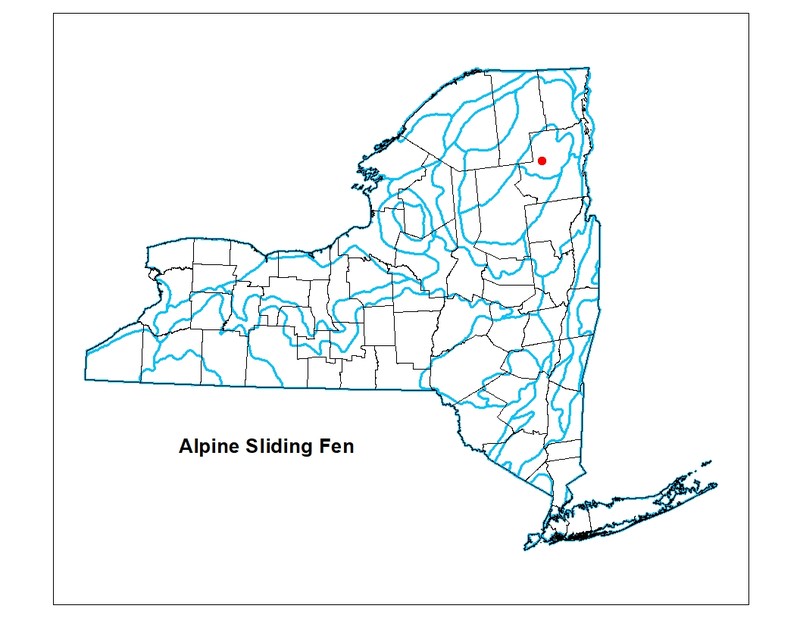

New York State Distribution

In New York, this community is restricted to the Adirondack High Peaks in Essex County.

Global Distribution

Alpine sliding fens are most likely restricted to the high peaks of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Requiring unique abiotic conditions (brow of slab, slide, or cliff), they are uncommon rangewide.

Best Places to See

- Whiteface Mountain Ski Center

- High Peaks Wilderness Area

Identification Comments

General Description

The sliding fen is a peatland perched on alpine bedrock at the top of bare slabs or cliffs. Sliding fens presumably become supersaturated from major rain events and slide off the cliff before peat build-up resumes (Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Water is derived from runoff and seeps at higher elevation. Reportedly the peat will accumulate until a critical mass is built up and the large areas of the peat mat slide to the bottom of the steep slope, a phenomenon that may occur once about every 500 years. Short shrub layer includes leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccus), bog bilberry (V. uliginosum), bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia), and green alder (Alnus viridis). Other small trees and shrubs include tamarack (Larix laricina) and Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum). Characteristic herbs include Pickering's reedgrass (Calamagrostis pickeringii), bulrush (Scirpus cespitosus), closed gentian (Gentiana linearis), round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), and sedge (Carex bigelowii). Other low-growing herbs include creeping snow-berry (Gaultheria hispidula) and mountain firmoss (Huperzia appalachiana). Characteristic mosses include peat mosses such as Sphagnum angustifolium, S. fallax, S. russowii, S. papillosum, S. pylaesii, and S. magellanicum. A rare peat moss of some sliding fens is Sphagnum lindbergii (Andrus 1980). Other mosses such as Andreaea spp. and Scapania nemorosa may be present. Various crustose lichens grow on the open bedrock areas.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This community is characterized as a shallow peat bog on 5-35 degree slopes on the brow of alpine or subalpine cliffs or slides. Pickering's reedgrass (Calamagrostis pickeringii), compact peatmoss (Sphagnum compactum), and other bog plants are found in these peatlands.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 4,068 feet and 4,331 feet.

Best Time to See

Mid to late summer offers a short window for the plants in this alpine community to flower. With luck, you might see the tiny, sticky fly-eating leaves of the sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) and catch the flowers of the small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccus), creeping snow-berry (Gaultheria hispidula), and others.

Alpine Sliding Fen Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Black Crowberry - Bog Blueberry - Small Cranberry / Cloudberry Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006140)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Acadian-Appalachian Alpine Tundra (CES201.567)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Alnus alnobetula ssp. crispa (green alder)

- Betula cordifolia (mountain paper birch)

- Kalmia polifolia (bog laurel)

- Picea rubens (red spruce)

- Rhododendron groenlandicum (Labrador-tea)

- Spiraea alba var. latifolia (broad-leaved meadow-sweet)

- Vaccinium oxycoccos (small cranberry)

-

Herbs

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Nabalus trifoliolatus (three-leaved rattlesnake-root)

- Oclemena acuminata (whorled wood-aster)

- Trichophorum cespitosum ssp. cespitosum (deer's-hair club sedge)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Andreaea

- Sphagnum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Inland poor fen

(guide)

Inland poor fens are generally located at lower elevations and lack the alpine species present in an alpine sliding fen. Alpine sliding fens also occur on a much steeper slope compared to the level inland poor fens.

- Open alpine community

(guide)

Open alpine community may have wet sections where peat has accumulated and the same species may be present. The alpine sliding fen however, is generally located on steeper slopes at the top of a bare-rock slab or cliff.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Alpine Sliding Fen. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Andrus, R.E. 1980. Sphagnaceae (Peat Moss Family) of New York State. Bulletin No. 442. New York State Museum. Albany, NY.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Sperduto, D.D. 2000. A classification of wetland natural communities in New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Sperduto, D.D. and C.V. Cogbill. 1999. Alpine and subalpine vegetation of the White Mountains, New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Sperduto, D.D. and W.F. Nichols. 2000. Exemplary bogs and fens of New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Sperduto, D.D., W.F. Nichols, and N. Cleavitt. 2000. Bogs and fens of New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Van Diver, Bradford B. 1985. Roadside Geology of New York. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, MT.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 27, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Alpine sliding fen.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/alpine-sliding-fen/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.