Open Alpine Community

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Many of the plants characteristic of the open alpine community have a circumboreal distribution, meaning they may also be found growing at localities around the globe in the arctic tundra of high latitudes. Open alpine communities are limited to the highest elevation areas of the state above timberline (about 3,500 feet).

State Ranking Justification

There are a limited number of open alpine communities statewide. This small patch community has much less than 200 acres in the state. Open alpine communities are limited to the highest elevation areas of the state above timberline (about 3,500 feet). The vegetation of the open alpine community is fragile and threatened by trampling by visitors. Although all occurrences are protected on state land, all are threatened by the combined effects of recreational overuse, atmospheric deposition, and possibly climate change.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of open alpine communities in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of conservation efforts at high elevation areas in the state.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of open alpine communities in New York have probably declined slightly from historical numbers likely correlated with minor development and recreational overuse on some summits.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The vegetation of the open alpine community is fragile because of shallow, nutrient-poor soils, a short growing season, and harsh microclimate conditions, thus the primary threat is recreational overuse that involves the trampling of fragile vegetation. Communities that occur at higher elevations in the state (e.g., >3,000 feet) may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of atmospheric deposition and climate change, especially acid rain and temperature increase. Unprotected examples of open alpine community may be threatened by development (e.g., communication towers) and recreational overuse (e.g., hiking trails, camp sites, ski slopes, and to a lesser extent ATV use).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Continue restoration efforts for severely trampled sites. Management activities should be consistent with recommendations presented in the High Peaks Wilderness Unit Management Plan (NYS DEC 1999).

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Construction of structures and trails should minimize the disturbance and subsequent erosion of the thin soils on which this community depends. Prioritize siting such development over open bedrock when possible.

Inventory Needs

A statewide review of alpine and high elevation (>3,000 feet) communities is desirable. Need quantitative data and monitoring plots within the open alpine community; need more work on lichens, bryophytes, and characteristic fauna.

Research Needs

Research the long-term combined effects that atmospheric deposition and climate change may have on the open alpine community. Compare the open alpine community in New York with types described in NH and VT (e.g., Sperduto and Cogbill 1999).

Rare Species

- Agrostis mertensii (Northern Bent) (guide)

- Anthoxanthum monticola ssp. monticola (Alpine Sweetgrass) (guide)

- Betula glandulosa (Tundra Dwarf Birch) (guide)

- Betula minor (Dwarf White Birch) (guide)

- Calamagrostis stricta (Northern Reed Grass) (guide)

- Carex bigelowii (Bigelow's Sedge) (guide)

- Diapensia lapponica (Diapensia) (guide)

- Empetrum atropurpureum (Purple Crowberry) (guide)

- Empetrum nigrum (Black Crowberry) (guide)

- Geocaulon lividum (False Toad Flax) (guide)

- Huperzia appressa (Mountain Firmoss) (guide)

- Nabalus boottii (Boott's Rattlesnake Root) (guide)

- Oreojuncus trifidus (Highland Rush) (guide)

- Poa flexuosa ssp. fernaldiana (Fernald's Blue Grass) (guide)

- Rhododendron lapponicum var. lapponicum (Lapland Rosebay) (guide)

- Salix herbacea (Snowbed Willow) (guide)

- Salix uva-ursi (Bearberry Willow) (guide)

- Solidago leiocarpa (Alpine Goldenrod) (guide)

- Trichophorum cespitosum ssp. cespitosum (Deer's Hair Club Sedge) (guide)

- Vaccinium boreale (Northern Lowbush Blueberry) (guide)

- Vaccinium cespitosum (Dwarf Bilberry) (guide)

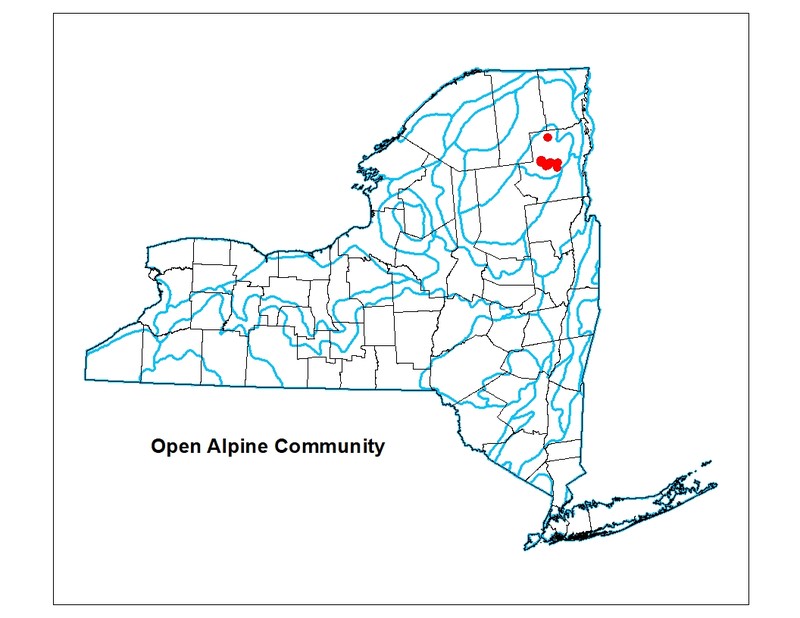

Range

New York State Distribution

In New York, this community is restricted to the Adirondack High Peaks in Essex County.

Global Distribution

Open alpine communities are essentially restricted to the high peaks of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. They are most abundant in New Hampshire where they approach large patch size. Small patches occur in New York and elsewhere.

Best Places to See

- Adirondack High Peaks Wilderness Area

- Whiteface Mountain Ski Center

Identification Comments

General Description

Characteristic species of the grass and sedge dominated areas include deer's hair sedge (Scirpus cespitosus), Bigelow's sedge (Carex bigelowii), bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis), alpine sweetgrass (Hierochloe alpina), common hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa), mountain woodrush (Luzula parviflora), arctic rush (Juncus trifidus), three-toothed cinquefoil (Potentilla tridentata), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), mountain sandwort (Minuartia groenlandica), and dwarf rattlesnake-root (Prenanthes nana). Characteristic species of the low shrubland areas are bog bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), dwarf birch (Betula glandulosa), black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), lapland rosebay (Rhododendron lapponicum), diapensia (Diapensia lapponica), and bearberry willow (Salix uva-ursi). On a few mountains there are distinctive patches of low shrublands consisting of dwarf birches including Betula glandulosa, B. minor, and stunted B. cordifolia. Characteristic species of the small boggy depressions include the peat mosses Sphagnum nemoreum and S. fuscum, cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum var. spissum), bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia), and small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos). Larger examples are recognized as "alpine bogs" in other northeast state classifications (Sperduto and Cogbill 1999, Sperduto 2000, Thompson and Sorenson 2000). Rock outcrops that are relatively undisturbed by trampling are covered with arctic-alpine lichens such as map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) and may have scattered cushions of diapensia. Characteristic birds include dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis) and white-throated sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis). This community is very sensitive to trampling because of the thin, often saturated soils and the very slow growth rate of the vegetation in the stressful alpine environment. Every effort should be made to minimize off-trail trampling by the many hikers who climb to the open alpine communities in the High Peaks.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The open alpine community is similar to arctic tundra. It occurs above timberline (about 4900 ft or 1620 m) on the higher mountain summits and also on some exposed ledges of the Adirondacks. This community consists of a mosaic of small grassy meadows, dwarf shrublands, small boggy depressions, and exposed bedrock covered with lichens and mosses. The flora includes arctic-alpine species that are restricted (in New York) to the open alpine community, as well as boreal species that occur in forests and bogs at lower elevations. The soils are thin and organic, primarily composed of sphagnum peat or black muck. The soils are often saturated because they can be recharged by atmospheric moisture.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 3,314 feet and 5,331 feet.

Best Time to See

Early summer is a good time to catch alpine flowers such as diapensia and three-toothed cinquefoil in bloom.

Open Alpine Community Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Bigelow's Sedge Alpine Meadow (CEGL006081)

- Pincushion Plant Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006322)

- Black Crowberry - Bog Blueberry - Small Cranberry / Cloudberry Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006140)

- Tufted Bulrush - Pickering's Reedgrass Alpine Snowbed (CEGL006423)

- Tufted Bulrush - Northern Single-spike Sedge - Bigelow's Sedge Alpine Snowbed (CEGL006424)

- Bog Blueberry - Mossplant - Alpine-azalea Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006155)

- Bog Blueberry - Lapland Rosebay / Highland Rush Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006298)

- Bog Blueberry / Three-toothed Cinquefoil Sparse Vegetation (CEGL006533)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Acadian-Appalachian Alpine Tundra (CES201.567)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Betula glandulosa (alpine birch, resin birch)

- Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf)

- Diapensia lapponica (pincushion-plant, diapensia)

- Empetrum atropurpureum (purple crowberry)

- Empetrum nigrum (black crowberry)

- Rhododendron groenlandicum (Labrador-tea)

- Rhododendron lapponicum (Lapland rose-bay)

- Salix uva-ursi (bearberry willow)

- Vaccinium boreale (northern lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium oxycoccos (small cranberry)

- Vaccinium uliginosum (bog bilberry)

-

Herbs

- Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis (Canada bluejoint grass)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Huperzia appressa (mountain firmoss)

- Mononeuria groenlandica (mountain-sandwort)

- Nabalus trifoliolatus (three-leaved rattlesnake-root)

- Oreojuncus trifidus (highland rush)

- Sibbaldia tridentata (three-toothed cinquefoil)

- Solidago leiocarpa (Cutler's alpine goldenrod)

- Trichophorum cespitosum ssp. cespitosum (deer's-hair club sedge)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Rhizocarpon geographicum

- Sphagnum fuscum

- Sphagnum nemoreum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Alpine krummholz

(guide)

Alpine krummholz is dominated (50-85%) by stunted (<1.5 m) balsam fir. The open alpine community consists of a mosaic of sedge/dwarf shrub meadows, dwarf heath shrublands, small boggy depressions, and exposed bedrock covered with lichens and mosses. Stunted tree cover <25%.

- Alpine sliding fen

(guide)

Open alpine community may have wet sections where peat has accumulated and the same species may be present. The alpine sliding fen however, is generally located on steeper slopes at the top of a bare-rock slab or cliff.

- Rocky summit grassland

(guide)

Rocky summit grasslands are located at lower elevations, at sites with exposed bedrock and thin soils. The open alpine community occurs above treeline on high mountain summits over 1,620 m (4,900 feet).

- Spruce-fir rocky summit

(guide)

Spruce-fir rocky summits have tree cover 25-60% with numerous rock outcrops. The open alpine community consists of a mosaic of sedge/dwarf shrub meadows, dwarf heath shrublands, small boggy depressions, and exposed bedrock covered with lichens and mosses. Stunted tree cover <25%.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Open Alpine Community. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

DiNunzio, M.G. 1972. A vegetational survey of the alpine zone of the Adirondack Mountains, New York. M.S. Thesis. SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Ketchledge, E.H. 1984. Adirondack Insights 15. The Alpine Flora. Adirondac 48(5): 17-20. (June issue of Adirondacks Magazine).

Ketchledge, E.H. and R.E. Leonard. 1984. A 24 - year comparison of the vegetation of an Adirondack mountain summit. Rhodora 86:439-444.

LeBlanc, D.C. 1981. Ecological studies on the alpine vegetation of the Adirondack Mountains of New York. M.A. Thesis. SUNY - Plattsburg. Plattsburg, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Robinson, S. 2004. An 18-Year Assessment of Vegetation Composition in the Adirondack Alpine Zone. Master of Science. Stte University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY. 95 pp.

Slack, Nancy G. and A.W. Bell. 1993. 85 acres: a field guide to the Adirondack alpine summits. Adirondack Mountain Club, Lake George, NY.

Slack, Nancy G. and A.W. Bell. 1995. Field guide to the New England alpine summits. Appalachian Mountain Club, Boston, MA.

Sperduto, D.D. and C.V. Cogbill. 1999. Alpine and subalpine vegetation of the White Mountains, New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Timothy G. Howard

Information for this guide was last updated on: April 3, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Open alpine community.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/open-alpine-community/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.