Inland Poor Fen

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Peatlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Did you know that certain inland poor fen plants, such as pitcher plants, use insect larvae to "eat" insects? Most plants receive their nutrients from the soil. However in nutrient poor soils of inland poor fens these plants digest insects to receive their nutrients. The pitcher plant has a hood-like "pitcher" leaf that holds water and nectar glands that attract insects. Insects are forced down the "pitcher" leaves into the water by downward pointed hairs. The insect is broken down by microorganisms and insect larvae that live in the plant's water. The nutrients from the insects are taken in by the plant. By early summer, the insect larvae reach their adult stage and fly away from the pitcher plant.

State Ranking Justification

There are several thousand occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is widespread throughout upstate New York, and includes several very large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure or alteration to the natural hydrology. This community has declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with peat mining, and logging and development of the surrounding landscape.

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of inland poor fens in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of wetland protection regulations. There may be a few cases of slight decline due to alteration of hydrology from impoundments (conversion to other palustrine community types).

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of inland poor fens in New York have probably declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with initial peat mining and logging of the surrounding landscape (increasing nutrient run-off into fens).

Conservation and Management

Threats

Inland poor fens are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., agricultural, residential, roads, railroads), recreational overuse (e.g., snowmobiles, hiking trails causing peat compaction), and habitat alteration in the adjacent landscape (e.g., logging, pollution, nutrient loading). Alteration to the natural hydrology is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, blocked culverts, beaver). Several examples of inland poor fen are threatened by invasive species, such as reedgrass (Phragmites australis).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of inland poor fens. A statewide review of the acidic peatlands is desirable, similar to the studies done in New Hampshire (Sperduto et al. 2000), Massachusetts (Kearsley 1999), and similar to what New York Natural Heritage did for rich fens (Olivero 2001).

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about inland poor fens, especially to advance our understanding of their classification, ecological processes (e.g., fire), hydrology, floristic variation, characteristic fauna, peat development, and succession. This research will provide the basic facts necessary to assess how human alterations in the landscape affect peatlands, and supply a framework for evaluating the relative value of poor fens (Damman and French 1987).

Rare Species

- Aeshna clepsydra (Mottled Darner) (guide)

- Aeshna subarctica (Subarctic Darner) (guide)

- Arethusa bulbosa (Dragon's Mouth Orchid) (guide)

- Betula pumila (Swamp Birch) (guide)

- Carex chordorrhiza (Creeping Sedge) (guide)

- Carex haydenii (Cloud Sedge) (guide)

- Carex livida (Livid Sedge) (guide)

- Carex wiegandii (Wiegand's Sedge) (guide)

- Euphagus carolinus (Rusty Blackbird) (guide)

- Neottia bifolia (Southern Twayblade) (guide)

- Orontium aquaticum (Golden Club) (guide)

- Papaipema appassionata (Pitcher Plant Borer Moth) (guide)

- Papaipema stenocelis (Chain Fern Borer Moth) (guide)

- Pyrola asarifolia ssp. asarifolia (Pink Shinleaf) (guide)

- Rhododendron canadense (Rhodora) (guide)

- Rhynchospora scirpoides (Long-beaked Beak Sedge) (guide)

- Scheuchzeria palustris (Pod Grass) (guide)

- Somatochlora forcipata (Forcipate Emerald) (guide)

- Somatochlora incurvata (Incurvate Emerald) (guide)

- Sparganium natans (Small Bur-reed) (guide)

- Symphyotrichum boreale (Northern Bog Aster) (guide)

- Williamsonia fletcheri (Ebony Boghaunter) (guide)

Range

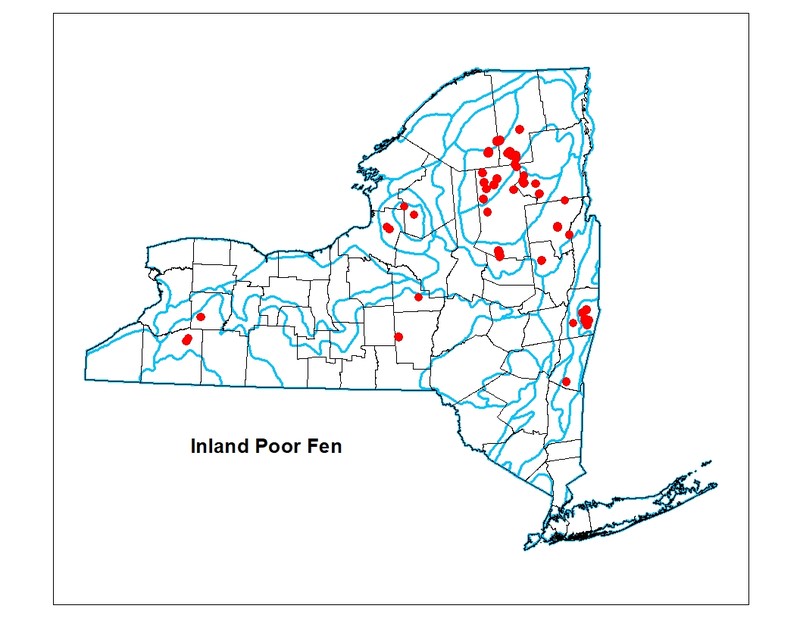

New York State Distribution

This community is widespread throughout upstate New York, north of the North Atlantic Coast Ecoregion. It is probably represented by different regional variants. It is concentrated in the Northern Appalachian Ecoregion where it approaches large patch size in a few occurrences.

Global Distribution

The range of this broadly-defined community may be worldwide. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are suspected to span north well into Canada, west to Minnesota, south possibly to West Virginia, and southeast to North Carolina, and NE to Nova Scotia.

Best Places to See

- Adirondack Park (St. Lawrence County)

- Pigeon Lake Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park (Hamilton County)

- High Peaks Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

- Fiddlers Green Preserve (Madison County)

- Boreal Heritage Preserve, Adirondack Park

- Capital District Wildlife Management Area (Rensselaer County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A weakly minerotrophic, flat peatland that occurs inland from the coastal plain in which the substrate is peat composed primarily of peat mosses (Sphagnum spp.) with admixtures of graminoid or woody peat. The dominant plants are peat mosses (Sphagnum spp.), with scattered sedges, shrubs, and stunted trees. Poor fens are fed by waters that are weakly mineralized, and have low pH values, generally between 3.5 and 5.0. This community typically develops where water moves through the peat mat, thus it often forms linear patches closely associated with open water. Many of our "kettlehole bogs" are inland poor fens, according to this classification, since they are weakly minerotrophic. Poor fens often include hummocks that are essentially ombrotrophic islands within a weakly minerotrophic peatland.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic peat mosses include Sphagnum angustifolium, S. cuspidatum, S. fallax, S. fuscum, S. magellanicum, S. papillosum, S. rubellum, and S. russowii. Characteristic herbs include sedges (Carex oligosperma, C. exilis, C. limosa, C. trisperma, C. utriculata, C. paupercula, C. canescens, C. michauxiana, C. parviflora), white beakrush (Rhynchospora alba), cottongrasses (Eriophorum vaginatum ssp. spissum, E. virginicum), round-leaf sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides), grass pink (Calopogon tuberosus), and pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea). Carex lasiocarpa may be present, but not dominant as in medium fens. A rare orchid of some inland poor fens is dragon's mouth (Arethusa bulbosa). Shrubs and dwarf shrubs are patchy and usually have less than 50% cover (i.e., not dominated by shrubs as in dwarf shrub bog). The taller sedges often overtop the short shrubs. Cranberries (Vaccinium oxycoccos, V. macrocarpon) are often dominant. Other characteristic shrubs include bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia), sheep laurel (K. angustifolia), sweet-gale (Myrica gale), black chokeberry (Photinia melanocarpa), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), bog rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla), and Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum). Scattered stunted trees such as tamarack (Larix laricina), black spruce (Picea mariana), and red maple (Acer rubrum) may be present.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 319 feet and 2,094 feet.

Best Time to See

Dwarf evergreen shrubs are important contributors to the flora of inland poor fens; their showy blooms are best seen in late spring and early summer. In early fall as the growing season ends, the peat mosses, evergreen shrubs, and tamarack form a warm tapestry of red, copper, and warm yellow tones.

Inland Poor Fen Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- (Few-seed Sedge, Coastal Sedge) - Leatherleaf Shrub Acidic Peatland (CEGL006524)

- (Toothed Peatmoss, Giant Peatmoss) - Cranberry Fen (CEGL006394)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Eastern Boreal-Sub-boreal Acidic Basin Fen (CES201.583)

- North-Central Interior and Appalachian Acidic Peatland (CES202.606)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Larix laricina (tamarack)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Larix laricina (tamarack)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Alnus incana ssp. rugosa (speckled alder)

- Andromeda polifolia var. glaucophylla

- Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry)

- Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf)

- Kalmia angustifolia var. angustifolia (sheep laurel, sheep-kill)

- Myrica gale (sweet gale)

- Rhododendron groenlandicum (Labrador-tea)

- Vaccinium oxycoccos (small cranberry)

- Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides (northern wild-raisin)

-

Herbs

- Carex exilis (meager sedge)

- Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana (slender bog sedge)

- Carex magellanica ssp. irrigua (bog sedge)

- Carex rostrata

- Carex stricta (tussock sedge)

- Carex trisperma (three-fruited sedge)

- Eriophorum virginicum (tawny cotton-grass)

- Hypericum virginicum (Virginia marsh St. John's-wort)

- Rhynchospora alba (white beak sedge)

- Sarracenia purpurea (purple pitcherplant)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Sphagnum fuscum

- Sphagnum magellanicum

- Sphagnum papillosum

- Sphagnum recurvum

- Sphagnum rubellum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal plain poor fen

(guide)

This poor fen type is restricted to the coastal plain of New York. Coastal plain poor fens tend to have higher pHs (4.0 to 5.5 versus 3.5 to 5.0) than inland poor fens, and thus support a somewhat more diverse flora.

- Dwarf shrub bog

(guide)

Dwarf shrub bogs are dominated (50% cover or more) by low (<1 m tall) heath shrubs, such as leatherleaf that overtops the short sedges and other bog herbs. Whereas, inland poor fens are dominated by taller sedges and other herbs that overtop the short shrubs. In addition, the inland poor fen shrub layer usually has less than 50% cover.

- Medium fen

(guide)

Inland poor fens are weakly minerotrophic peatlands with a substrate composed primarily of Sphagnum moss with scattered sedges, shrubs, and stunted trees. Although woolly-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana) and sweet gale (Myrica gale) can sometimes be found in inland poor fens, they are not dominant. Medium fens tend to have slightly higher pHs (4.5 to 6.5 versus 3.5 to 5.0) than inland poor fens.

- Rich shrub fen

(guide)

Inland poor fens are dominated by taller sedges and other herbs that overtop the short shrubs, such as leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), and the peat is more acidic (pH 3.5-5.0) than rich shrub fens (pH 6.0-7.8). Rich shrub fens are dominated (50% cover or more) by rich indicator shrubs, such as alderleaf buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia), shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora floribunda), poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), hoary willow (Salix candida), and bog birch (Betula pumila).

- Sedge meadow

(guide)

Sedge meadows are open wetlands dominated by tussock sedge (Carex stricta) with bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis) as a common codominant. Tussock sedge may be present in inland poor fens, but it usually makes up less than 50% cover.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Inland Poor Fen. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Andrus, R.E. 1980. Sphagnaceae (Peat Moss Family) of New York State. Bulletin No. 442. New York State Museum. Albany, NY.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Damman, A.W.H. and T.W. French. 1987. The ecology of peat bogs of the glaciated northeastern United States: a community profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report 85(7.16). 100 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Langdon, Stephen F., M. Dovciak, and D.J. Leopold. 2020. Tree Encroachment Varies by Plant Community in a Large Boreal Peatland Complex in the Boreal-Temperate Ecotone of Northeastern USA. Wetlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01319-z

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Slack, Nancy G. 1994. Can one tell the mire type from the bryophytes alone? J. Hattori Bot. Lab 75:149-159.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: February 5, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Inland poor fen.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/inland-poor-fen/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.