Backwater Slough

- System

- Riverine

- Subsystem

- Natural Streams

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2S3

Imperiled or Vulnerable in New York - Very vulnerable, or vulnerable, to disappearing from New York, due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign either S2 or S3.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

The word 'slough' can be pronounced in two different ways, each with a different meaning. When pronouned 'slew' or 'slue', it refers to either an "area of soft muddy ground" or a "marshy or reedy pool, pond, inlet, backwater, or the like." The pronounciation 'sluff' indicates an outer layer of skin (often of a snake), which is cast off periodically.

State Ranking Justification

There are probably much less than a thousand occurrences statewide. Very few documented occurrences have good viability and few are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has statewide distribution, and includes a few large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include alteration of the natural hydrology and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

The number and miles of backwater sloughs associated with unconfined rivers in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of water quality regulations. Several examples have shown improvement in water quality in recent decades attributed to improved treatment of municipal and industrial waste (Bode et al. 1993).

Long-term Trends

The number and miles of backwater sloughs associated with unconfined rivers in New York are probably comparable to historical numbers, but the water quality of several of these rivers has likely declined significantly prior to the enforcement of water quality regulations (New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Water 2000).

Conservation and Management

Threats

Backwater sloughs are threatened by development (e.g., residential, agricultural) in the surrounding landscape. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., road crossings, excessive logging in adjacent floodplain), and relatively minor recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, trampling by visitors). Threats to adjacent rivers may apply to backwater sloughs (e.g., channelization, pollution, nutrient loading, sedimentation, impoundments/flooding).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a riparian buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the backwater slough. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the slough and surrounding landscape. For example, roads should not be routed through the riparian buffer area. If the slough must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling and culverts. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the backwater slough through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities, minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as runoff usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the system, they bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algal blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment in which few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of backwater sloughs. A statewide review of backwater sloughs is desirable. Continue searching for backwater sloughs in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about backwater sloughs, especially to advance our understanding of their classification, hydrology, floristic variation, and characteristic fauna.

Rare Species

Range

New York State Distribution

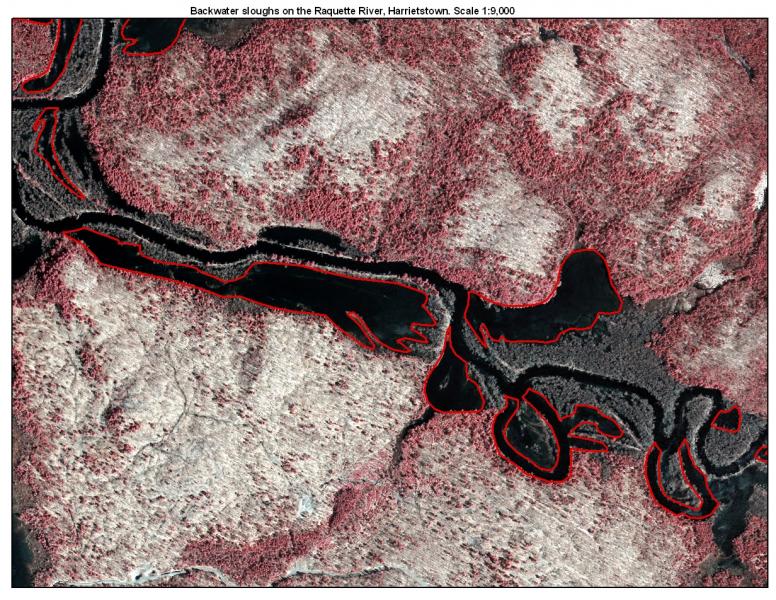

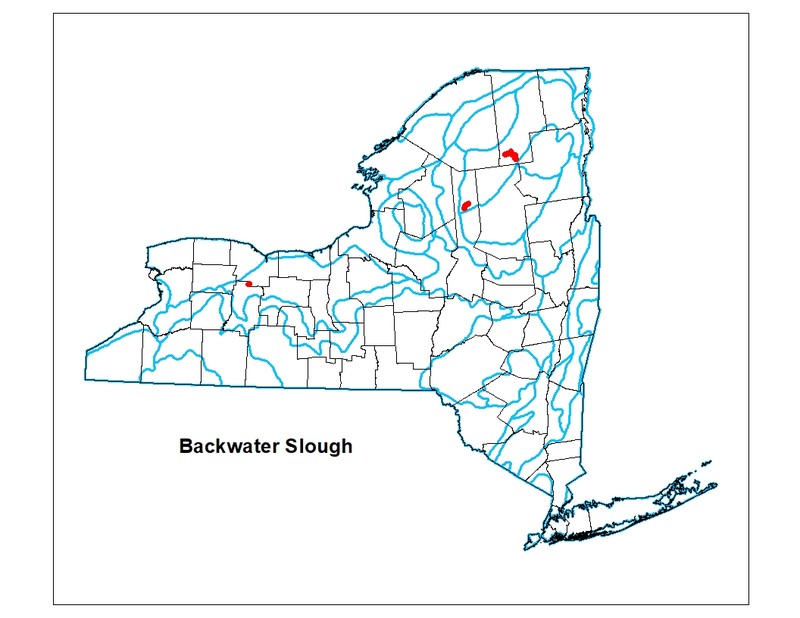

This community is currently known from the central Adirondacks and the Lake Ontario Lake Plain, but may also occur along other larger rivers across the state.

Global Distribution

This broadly-defined community may be worldwide. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are estimated to span north to southern Canada, west to Minnesota, southwest to Indiana and Tennessee and southeast to Georgia.

Best Places to See

- Saranac Lakes Wild Forest

- Sargent Ponds Wild Forest (Hamilton County)

- High Peaks Wilderness Area

- Log Pond Flats (Livingston County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A backwater slough consists of the aquatic community of quiet to stagnant, typically warm waters located in embayments and old meanders. Although classified as part of a riverine system, many hydrological characteristics resemble those of lacustrine communities. Examples of this river type may be relatively short-lived in dynamic river complexes, transforming into oxbow lakes through permanent formation of downstream levees or into associated river types through permanent breaching of the upstream levee. Four to seven ecoregional variants are suspected to exist in New York and differ in dominant and characteristic vascular plants, fishes, mollusks, insects, and birds as well as in water chemistry, water temperature, underlying substrate type, surrounding forest type and associated stream type.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Backwater sloughs are only connected to associated riverine communities at their downstream end and are often bounded by an upstream levee. Characteristic biota are pool specialists and may resemble lacustrine or marsh headwater stream species assemblages. Aquatic vegetation is usually abundant; characteristic aquatic plants include waterweed (Elodea canadensis), milfoil (Myriophyllum spp.), duckweed (Lemna minor), and pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.). Emergent aquatic plants such as green arrow-arum (Peltandra virginica), pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata), common arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia), and swamp loosestrife (Decodon verticillatus) may be abundant along the shores. Characteristic fishes are golden shiner (Notemigonus crysoleucas), pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus), brown bullhead (Ictalurus nebulosus), and chain pickerel (Esox niger). Macroinvertebrates may include odonates (Odonata), stoneflies (Plecoptera), diving beetles (Dytiscidae), mosquitoes (Cuculidae), true flies (Tipula spp., Atherix spp., Simulum spp.), midges (Chironomidae), crustaceans (Hyalella spp.), clams (Pisdium spp.) and mayflies (Stenonema). Wading birds and other water birds such as pied-billed grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) and great blue heron (Ardeas herodias) may be characteristic. A characteristic mammal may be muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 535 feet and 1,731 feet.

Best Time to See

The best time to view the diversity of emergent plants in a backwater slough in bloom is in the summer, from June through August.

Backwater Slough Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Pickerelweed - Green Arrow-arum - Broadleaf Arrowhead Marsh (CEGL006191)

- American Eel-grass - Claspingleaf Pondweed Aquatic Vegetation (CEGL006196)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Laurentian-Acadian Freshwater Marsh (CES201.594)

Characteristic Species

-

Emergent aquatics

- Carex aquatilis (water sedge)

- Carex vesicaria (lesser bladder sedge)

- Cicuta bulbifera (bulb-bearing water-hemlock)

- Decodon verticillatus (water-willow)

- Dulichium arundinaceum var. arundinaceum (three-way sedge)

- Eleocharis palustris (common spike-rush)

- Eleocharis robbinsii (Robbins's spike-rush)

- Equisetum fluviatile (river horsetail)

- Eriocaulon aquaticum (northern pipewort, northern hat-pins)

- Glyceria canadensis (rattlesnake manna grass)

- Hypericum mutilum ssp. mutilum (dwarf St. John's-wort)

- Juncus pelocarpus (brown-fruited rush)

- Leersia oryzoides (rice cut grass)

- Lysimachia terrestris (swamp-candles)

- Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife)

- Peltandra virginica (green arrow-arum, tuckahoe)

- Pontederia cordata (pickerelweed)

- Rhynchospora alba (white beak sedge)

- Sagittaria latifolia (common arrowhead)

- Sparganium americanum (American bur-reed)

-

Floating-leaved aquatics

- Brasenia schreberi (water-shield)

- Lemna minor (common duckweed)

- Nuphar microphylla × N. variegata = N. ×rubrodisca (red-disked yellow pond-lily, red-disked spatter-dock)

- Nymphaea odorata ssp. odorata (fragrant white water-lily)

- Potamogeton amplifolius (big-leaved pondweed)

-

Submerged aquatics

- Eleocharis robbinsii (Robbins's spike-rush)

- Elodea canadensis (Canada waterweed)

- Myriophyllum sibiricum (northern water milfoil)

- Najas sp.

- Potamogeton amplifolius (big-leaved pondweed)

- Potamogeton spp.

- Utricularia cornuta (horned bladderwort)

- Utricularia intermedia (flat-leaved bladderwort)

- Utricularia purpurea (purple bladderwort)

- Vallisneria americana (water-celery, tape-grass)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Oxbow lake/pond

(guide)

An oxbow lake is a stagnant lake or pond that forms when a river meander is cut off from the mainstem by the formation of a levee on both the upstream and downstream ends. A backwater slough is only cut off from the mainstem by an upstream levee.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Backwater Slough. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Bode, R.W., M.A. Novak, and L.E. Abele. 1993. Twenty year trends in water quality of rivers and streams in New York State based on macroinvertebrate data 1972-1992. New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Water, Albany, NY.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Water. 2000. New York State water quality 2000. October 2000. New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Water, Albany, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. No date. Field forms database: Electronic field data storage and access for New York Heritage ecology, botany, and zoology. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Smith, C.L. 1985. The Inland Fishes of New York State. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 522pp.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 14, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Backwater slough.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/backwater-slough/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.