Calcareous Pavement Woodland

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Barrens And Woodlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2S3

Imperiled or Vulnerable in New York - Very vulnerable, or vulnerable, to disappearing from New York, due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign either S2 or S3.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Calcareous pavement woodlands are underlain by limestone bedrock. Limestone refers to rock formed mostly of calcium carbonate, but to geologists, limestone is only one of several types of "carbonate rocks." These rocks are composed of more than 50% carbonate minerals, generally the minerals calcite or dolomite (calcium-magnesium carbonate) or both.

State Ranking Justification

There are probably much less than 50 occurrences statewide. A few documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is limited to the calcareous regions of the state, and there are only a few high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land and private conservation land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include conversion to pastureland, development, trampling by visitors, ATVs, and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of calcareous pavement woodlands in New York have probably declined slightly in recent decades as a result of development, conversion to pastureland, recreational ATVs, and invasive species.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of calcareous pavement woodlands in New York have probably declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with past conversion to pastureland.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Calcareous pavement woodlands are threatened by development (e.g., conversion to agricultural uses such as pastureland, residential, industrial), either directly within the community or in the surrounding landscape. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., road crossings, intensive cedar logging, mining) and relatively minor recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, trampling by visitors, trash dumping). Deer overbrowsing may be a threat at a few sites. Several calcareous pavement barrens are threatened by invasive species, such as black swallow-wort (Cynanchum louiseae), Morrow's honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii), and buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Increase and/or maintain the size of existing calcareous pavement woodlands by increasing patch size where appropriate, by "softening" the abrupt forest edges by maintaining a native shrub transition zone. Improve the condition of existing calcareous pavement barrens by reducing and/or eliminating invasive species, such as black swallow-wort (Cynanchum louiseae), Morrow's honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii), and buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). Improve barrens by minimizing trail network and clearly marking existing trails, and developing and implementing a prescribed burn plan at appropriate sites. Improve the landscape context of the barrens by encouraging surrounding landowners to establish natural buffers and restore natural corridors to other larger natural landscape blocks.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

A natural (usually forested) buffer around the edges of this community will help it maintain the microclimatic characteristics that help make this community unique.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of calcareous pavement woodlands. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked). Periodic inventory of the calcareous pavement woodlands is needed, in order to keep occurrence data current.

Research Needs

Research the composition of calcareous pavement woodlands statewide in order to characterize variations.

Rare Species

Range

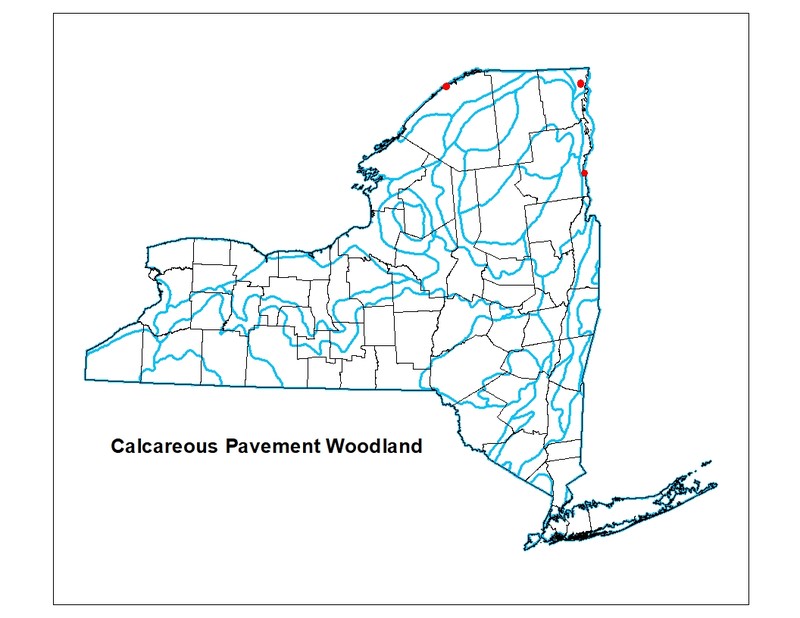

New York State Distribution

The best sites are concentrated in the St. Lawrence Glacial Lake Plain Subsection of the St. Lawrence (non-alvar areas) and Champlain Valley Ecoregion. Other examples are located in the Eastern Ontario Lake Plain, the St. Lawrence Glacial Marine Plain, and Champlain Glacial Lake and Marine Plain. Additional small sites occur along the Onondaga Escarpment and the Helderberg Highlands.

Global Distribution

The range is estimated to span north to southern Ontario, west to northern Michigan, south to the Helderburg Highlands of central New York and east to the Lake Champlain Valley of New York and Vermont.

Best Places to See

- Valcour Island

- Thacher State Park

- Clark Reservation (Onondaga County)

- Crown Point State Historic Site

Identification Comments

General Description

The tree canopy layer is sparse and often grows in clumps. Characteristic trees include northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), hop hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa), white ash (Fraxinus americana), red maple (Acer rubrum), and white pine (Pinus strobus). Characteristic shrubs include seedlings and saplings of trees listed above plus shrubby dogwoods (Cornus racemosa, C. amomum), common juniper (Juniperus communis), fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica), and prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum). Characteristic herbs include a mix of native and non-native species including Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), poverty-grass (Danthonia spicata), gray goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis), panic grasses (Panicum flexile, Dichanthelium acuminatum), prairie fleabane (Erigeron strigosus var. strigosus), American pennyroyal (Hedeoma pulegioides), balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula), Queen-Anne's-lace (Daucus carota), hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.), clovers (Trifolium spp.), ebony sedge (Carex eburnea), upland white aster (Oligoneuron album), herb robert (Geranium robertianum), and wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana). Fruticose and foliose lichens are locally common in the grassy areas, including reindeer lichens (Cladonia spp.) and cup lichen (Cladonia pocillum). Characteristic mosses include hair cap moss (Polytrichum spp.) and Tortella tortuosa.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This community is an open canopy woodland that occurs on very shallow soils over flat, striated outcrops of calcareous bedrock (limestone and dolomite). This community includes patches of sparsely vegetated rock rubble in between dense cedar clumps or grassy open areas. This woodland is not typically found in an alvar ecosystem, but is often associated with limestone woodlands.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 130 feet and 320 feet.

Best Time to See

Calcareous pavement woodlands offer a nice array of spring ephemerals and early wildflowers from May to June.

Calcareous Pavement Woodland Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern White-cedar Limestone Bedrock Woodland (CEGL005050)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Thuja occidentalis (northern white cedar, arbor vitae)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Cornus amomum ssp. amomum (silky dogwood)

- Cornus racemosa (gray dogwood, red-panicled dogwood)

- Juniperus communis var. depressa (American common juniper, ground juniper)

- Rhus aromatica var. aromatica (fragrant sumac)

- Zanthoxylum americanum (prickly-ash)

-

Tree saplings

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Thuja occidentalis (northern white cedar, arbor vitae)

-

Herbs

- Danthonia spicata (poverty grass)

- Dichanthelium columbianum (District of Columbia rosette grass)

- Erigeron strigosus strigosus

- Fragaria virginiana ssp. virginiana (common wild strawberry)

- Geranium robertianum (herb-Robert)

- Hedeoma pulegioides (American-pennyroyal)

- Packera paupercula (balsam groundsel)

- Panicum flexile (wiry witch grass)

- Poa compressa (flat-stemmed blue grass, Canada blue grass)

- Solidago nemoralis ssp. nemoralis (gray goldenrod)

- Solidago ptarmicoides (upland white flat-topped-goldenrod)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Cladonia pocillum

- Cladonia spp.

- Poytrichum spp.

- Tortella tortuosa

Similar Ecological Communities

- Alvar pavement grassland

(guide)

Calcareous pavement woodlands have over 25% cover of trees 5 m or taller. Alvar pavement grasslands typically lack trees, but a few sparsely scattered trees may grow in the cracks of the limestone pavement. Calcareous pavement woodlands occur statewide in areas underlain by various limestone bedrock types in a non-alvar landscape. Alvar pavement-grasslands occur on Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex) within a mosaic of other alvar communities.

- Alvar woodland

(guide)

Calcareous pavement woodlands occur statewide in areas underlain by various limestone bedrock types in a non-alvar landscape. Alvar woodlands occur on Chaumont limestone (Galoo-Rock outcrop complex) within a mosaic of other alvar communities.

- Limestone woodland

(guide)

Calcareous pavement woodlands are more open and have larger areas of exposed, flat bedrock than limestone woodland. Limestone woodlands have a more continuous ground layer and the rock outcrops are usually smaller and not necessarily flat .

- Sandstone pavement barrens

(guide)

Calcareous pavement woodlands occur statewide in areas underlain by various limestone bedrock types and lack jack pine. Sandstone pavement barrens are underlain by non-calareous Potsdam Sandstone and jack pine is common.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Calcareous Pavement Woodland. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Gregory J. Edinger

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 13, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Calcareous pavement woodland.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/calcareous-pavement-woodland/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.