Coastal Oak-Laurel Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

The genus of mountain laurel, Kalmia, was named by Carolus Linneaus in honor of one of his students, Swedish botanist Pehr Kalm. Kalm began his botanical career in Sweden and traveled extensively doing field research. Kalm kept a journal during his time in North America that continues to be an important source of information on early life in the colonies.

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 3 to 20 extant occurrences statewide. Heavy deer browse and exotic species invasion are additional threats. Most occurrences are on private or public conservation land, however some have questionable viability. The community is restricted to interior portions of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in New York in Suffolk County and is concentrated on knolls and mid to upper slopes of moraines. The acreage, extent, and condition of coastal oak-laurel forests in New York is suspected to be declining. They are vulnerable to fragmentation and extirpation by continued residential development.

Short-term Trends

The acreage, extent, and condition of coastal oak-laurel forests in New York is suspected to be declining, primarily due to fragmentation and extirpation from residential development, heavy deer browse, and exotic species invasion.

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of coastal oak-laurel forests in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in landscape connectivity.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Coastal oak-laurel forests are vulnerable to fragmentation and extirpation from further residential development. Heavy deer browse and exotic species invasion are additional threats.Occurrences located on protected public land are under threat of displacement from intensive recreational uses, including golf courses, horseback riding trails, off-road vehicle activity, ball fields, and other park facilities.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

To promote a dynamic forest mosaic, allow natural processes, including gap formation from blowdowns and tree mortality as well as in-place decomposition of fallen coarse woody debris and standing snags, to operate, particularly in mature and old growth examples (Spies and Turner 1999). Management efforts should focus on the control or local eradication of invasive exotic plants and the reduction of white-tailed deer densities. Consider deer exclosures or population management, particularly if studies confirm that canopy species recruitment is being affected by heavy browse. Generally, management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that tree and shrub seedlings are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. If active forestry must occur, use silvicultural techniques and extended rotation intervals that promote regeneration of a diversity of canopy, subcanopy, and shrub species over time (Busby et al. 2009) while avoiding or minimizing both short-term and persistent residual disturbances such as soil compaction, loss of canopy cover due to logging road construction, and the unintended introduction of invasive exotic plants.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Fragmentation of coastal forests should be avoided. It is also important to maintain connectivity with adjacent natural communities not only to allow nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but to allow animals to move between them seasonally. Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Surveys for additional large examples are needed. Priority focus areas are the eastern half of the Ronkonkoma Moraine and the western part of the Harbor Hill Moraine. Primary leads include Long Pond Greenbelt and Culloden Point. Other leads include sites mentioned in Greller (1977): Cold Spring Hills, Manetto Hills and Dix Hills. More data on associated species is needed. Additional surveys of the occurrences on the morainal hills of western Long Island (NW Suffolk County and NE Nassau County) are needed to confirm their identity.

Research Needs

A critical assessment of the long-term effects of heavy deer browse on this community, particularly addressing oak and other canopy species seedling recruitment, is needed. An investigation of the correlation between Kalmia latifolia and Quercus coccinea abundance is also needed.

Rare Species

Range

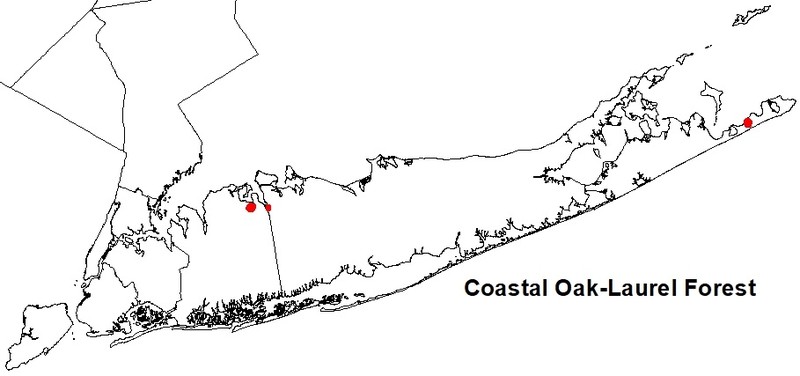

New York State Distribution

Restricted to interior portions of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in New York in Suffolk County; concentrated on knolls and mid to upper slopes of moraines. Known examples range from Hither Hills west possibly to the morainal hills of northwestern Suffolk County. Several examples occur along the eastern half of the Ronkonkoma Moraine. The community range possibly extends westward into eastern Nassau County on the end moraine of western Long Island.

Global Distribution

The distribution of this type is centered in New Jersey and Long Island, New York, with known occurrences also present in New Hampshire and Delaware. It may also occur in surrounding states (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Hither Hills State Park (Suffolk County)

- Cold Spring Harbor State Park (Suffolk County)

- Tiffany Creek Preserve (Nassau County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A large patch low diversity hardwood forest with broadleaf canopy and evergreen subcanopy that typically occurs on dry well-drained, sandy and gravelly soils of morainal hills of the Atlantic Coastal Plain. This forest is similar to the chestnut oak forest of the Appalachian Mountains; it is distinguished by lower abundance of chestnut oak (Quercus montana) and absence of red oak (Quercus rubra), probably correlated with the difference between the sand and gravel of glacial moraines versus the bedrock of mountains. Coastal oak-laurel forest is often associated with coastal oak-heath forest, forming a forest complex on morainal hills.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The dominant tree is typically scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea). Common associates are white oak (Q. alba), black oak (Q. velutina), and chestnut oak. The shrub layer is well-developed, typically with a tall, often nearly continuous cover of the evergreen heath, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia). Other characteristic shrubs include black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) and blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum). The herbaceous layer is very sparse; characteristic species are bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum), wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), and Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 30 feet and 220 feet.

Best Time to See

Late spring is probably the best time to see this forest since this is the time when mountain laurel showcases its beautiful white/pale pink floral display.

Coastal Oak-Laurel Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Black Oak - Scarlet Oak - Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest (CEGL006374)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dry Oak-Hardwood Forest (CES203.475)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Betula lenta (black birch)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

- Liriodendron tulipifera (tulip tree, tulip poplar, yellow poplar)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Cornus florida (flowering dogwood)

- Kalmia latifolia (mountain laurel)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Kalmia latifolia (mountain laurel)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Rhododendron periclymenoides (pinxter-flower)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

- Viburnum acerifolium (maple-leaved viburnum)

-

Herbs

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Chimaphila maculata (spotted-wintergreen)

- Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen, teaberry)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum (eastern bracken fern)

- Pyrola elliptica (common shinleaf)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Leucobryum glaucum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Chestnut oak forest

(guide)

Chestnut oak forest is dominated by chestnut oak and red oak (Quercus rubra). Coastal oak-laurel forest is dominated by scarlet oak, has a lower abundance of chestnut oak, and has no red oak.

- Coastal oak-heath forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-heath forest is codominated by a mix of oak species, including scarlet oak, white oak, and black oak with a shrub layer that is dominated by heath species (blueberry or huckleberry). Coastal oak-laurel forest is more strongly dominated by scarlet oak with a tall, continuous cover of mountain laurel in the shrub layer.

- Coastal oak-hickory forest

(guide)

This is a large patch low diversity hardwood forest with broadleaf canopy and evergreen subcanopy that typically occurs on dry well-drained, sandy and gravelly soils of morainal hills of the Atlantic coastal plain. This forest is similar to the chestnut oak forest of the Appalachian Mountains; it is distinguished by lower abundance of chestnut oak (Quercus montana) and absence of red oak (Quercus rubra), probably correlated with the difference between the sand and gravel of glacial moraines versus the bedrock of mountains.

- Coastal oak-holly forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-holly forests are dominated by black oak, black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), red maple (Acer rubrum) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia) with laurel absent or in very low abundance. Holly (Ilex opaca) is abundant in the subcanopy and tall shrub layers. Coastal oak-laurel forest is dominated by scarlet oak with lesser amounts of white, black, and chestnut oak; no black gum; and no American beech.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Coastal Oak-Laurel Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Busby, Posy E., C. D. Canham, G. Motzkin, and D. R. Foster. 2009. Forest response to chronic hurricane disturbance in coastal New England. Journal of Vegetation Science 20: 487-497.

Cain, S.A. 1936. The composition and structure of an oak woods, Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, with special attention to sampling methods. American Midland Naturalist 19: 390-416.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 140 (4):376-382.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson and K. Metzler. 1996. Community alliances and elements of the eastern region. Second draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Region Conservation Science, Boston, MA. April 11. 234 pp.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson, and J. Lundgren. 1998. International classification of ecological communities: terrestrial vegetation of the northeastern United States. July 1998 working draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science and Natural Heritage ProgramS of the northeastern United States, Boston, MA. July 1998.

Spies, T.A. and M.G. Turner. 1999. Dynamic forest mosaics. Pages 95-160 in: M. L. Hunter, Jr., editor. Maintaining biodiversity in forest ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Thompson, John E. 1997. Ecological communities of the Montauk Peninsula, Suffolk County, New York. Prepared for The Nature Conservancy, Long Island Chapter. April 1997.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coastal oak-laurel forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/coastal-oak-laurel-forest/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.