Coastal Oak-Heath Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

These coastal oak-heath forests provide critical wildlife food resources, including huckleberries and blueberries that ripen in the summer and mast acorns from oaks that mature in the fall. Wildlife biologists can estimate the size of the population of deer, wild turkey, and squirrel by monitoring the mast production of acorns from oaks. Mast food availability has also been found to reflect antler development and reproductive success among yearling deer. Mast production is influenced by many factors such as annual rainfall, wind, temperature, and weather events, which in turn can affect wildlife populations (Suchy 2006).

State Ranking Justification

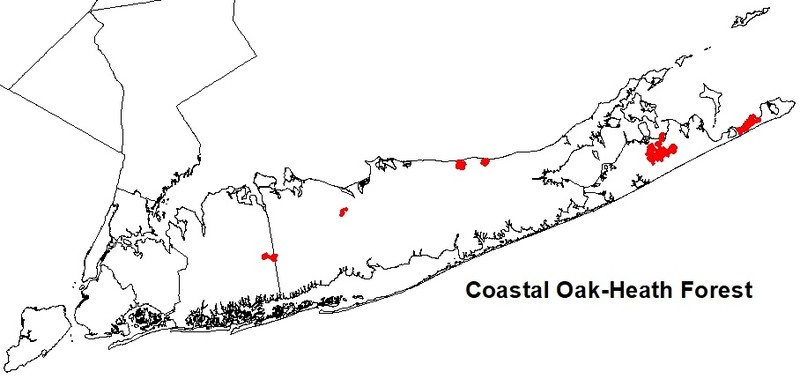

There are less than 10 fairly large occurrences of this natural community on Long Island. Many of the documented occurrences are protected on public land or private conservation land. This natural community is probably stable for the occurrences on public land and possibly declining slightly elsewhere due to development pressure.

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of coastal oak-heath forests in New York have moderately declined in recent decades. This decline is due to to displacement from residential and commercial development.

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of coastal oak-heath forests have declined from historical numbers due to settlement of the area and the subsequent agricultural, residential, and commercial development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The threats to the coastal oak-heath forest are many and varied: fragmentation of the forest by roads, trails, and powerlines causing a loss of the forest core; recreational, residential and commercial development; erosion from trails, roads, and trampling; fire suppression; and deer browse. This is a fire adapted community and the loss of regular fires would cause gradual successional changes to a different community type. Over-browsing by deer will also cause a change to the community by prohibiting the regeneration of tree canopy species.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

To promote a dynamic forest mosaic, allow natural processes, including gap formation from blowdowns and tree mortality as well as in-place decomposition of fallen coarse woody debris and standing snags, to operate, particularly in mature and old growth examples (Spies and Turner 1999). Management efforts should focus on the control or local eradication of invasive plants and the reduction of white-tailed deer densities. Consider deer exclosures or population management, particularly if studies confirm that canopy species recruitment is being affected by heavy browse. Generally, management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that tree and shrub seedlings are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. If active forestry must occur, use silvicultural techniques and extended rotation intervals that promote regeneration of a diversity of canopy, subcanopy and shrub species over time (Busby et al. 2009) while avoiding or minimizing both short-term and persistent residual disturbances such as soil compaction, loss of canopy cover due to logging road construction, and the unintended introduction of invasive plants.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Fragmentation of coastal forests should be avoided. It is also important to maintain connectivity with adjacent natural communities not only to allow nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but to allow animals to move between them seasonally. Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Surveys for additional large examples are needed, particularly on the periphery of the Long Island Pine Barrens. Primary leads include Sears-Bellows Park, Connetquot River State Park, Yaphank area (including South Haven and Brookhaven Labs, see Reiners, 1967), Warbler Woods, and Half Hollow Hills. Other leads include Caleb Smith State Park, and possibly Wildwood State Park, Kings Park, Jaynes Hill, S of Happauge, Commack, and Hicksville. Data collection to more critically evaluate the ranks of the occurrences at Barcelona Neck and Montauk Mountain is needed.

Research Needs

Research is needed to critically assess the long-term effects of heavy deer browse on this natural community. Research should focus on sapling and seedling regeneration of the forest canopy species particularly the oaks.

Rare Species

- Abagrotis benjamini (Coastal Heathland Cutworm) (guide)

- Ageratina aromatica var. aromatica (Small White Snakeroot) (guide)

- Asclepias variegata (White Milkweed) (guide)

- Callophrys irus (Frosted Elfin) (guide)

- Calycopis cecrops (Red-banded Hairstreak) (guide)

- Carex reznicekii (Reznicek's Sedge) (guide)

- Crataegus uniflora (Dwarf Hawthorn) (guide)

- Crocanthemum propinquum (Low Rock Rose) (guide)

- Hypericum stragulum (Low St. John's Wort) (guide)

- Lasiurus borealis (Eastern Red Bat) (guide)

- Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) (guide)

- Pinus virginiana (Virginia Pine) (guide)

- Pyrrhia aurantiago (Aureolaria Seed Borer) (guide)

- Tripsacum dactyloides (Northern Gama Grass) (guide)

Range

New York State Distribution

This natural community is restricted to interior portions of the coastal lowlands region away from direct maritime influence. Coastal oak-heath forests are concentrated on outwash plains and possibly knolls and mid to upper slopes of glacial moraines. The community range possibly extends westward into eastern Nassau County on the end moraine of western Long Island and has been reported from a narrow strip of outwash on the north shore of Long Island.

Global Distribution

The range of this natural community is somewhat restricted. This community occurs in coastal areas from New Hampshire to New Jersey on rapidly drained soils north of the glacial border.

Best Places to See

- Caleb Smith State Park Preserve (Suffolk County)

- Wildwood State Park (Suffolk County)

- Long Pond Greenbelt Preserve (Suffolk County)

- North Haven State Tidal Wetlands (Suffolk County)

- Sag Harbor State Park (Suffolk County)

- Bethpage State Park (Nassau County)

- Barcelona Neck Natural Resource Management Area (Suffolk County)

- Hither Hills State Park (Suffolk County)

- Northwest Creek SCFWH (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

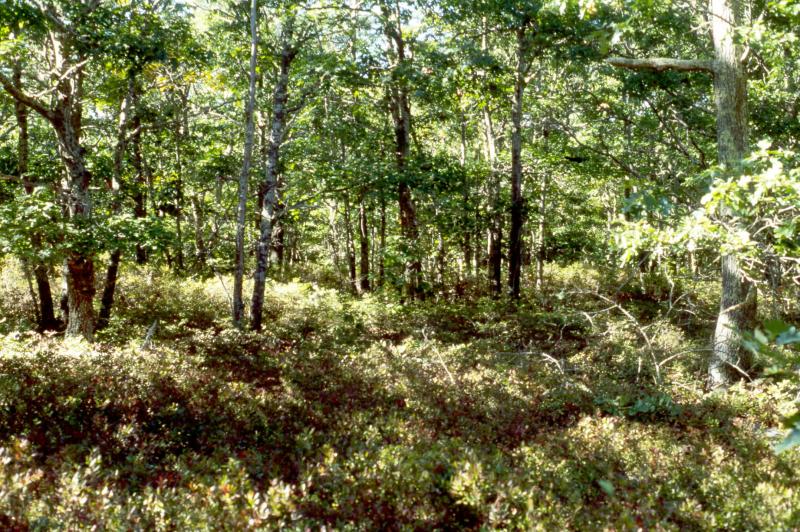

The forest is usually codominated by two or more species of oaks: scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), white oak (Q. alba) and black oak (Q. velutina). Chestnut oak (Quercus montana) is also a common associate. Pitch pine (Pinus rigida) and trees of other genera, if present, typically occur at less than 1% cover each in the canopy. American chestnut (Castanea dentata) may have been a common associate in these forests prior to the chestnut blight; chestnut sprouts are still found in some stands. The shrublayer is well-developed typically with a low nearly continuous cover of dwarf heaths such as blueberries (Vaccinium pallidum, V. angustifolium) and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata). The herbaceous layer is very sparse; characteristic species are bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), and Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica). Herb diversity is greatest in natural and artificial openings with species such as frostweed (Helianthemum canadense), false-foxglove (Aureolaria spp.), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), goat's-rue (Tephrosia virginiana), bush-clovers (Lespedeza spp.), and pinweeds (Lechea spp.).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A low diversity, large patch to matrix, hardwood forest dominated by oaks and hickories with a well developed short shrub layer dominated by huckleberries (Gaylussacia spp.) and blueberries (Vaccinium spp.). This natural community occurs on dry, well-drained, sandy soils of glacial outwash plains or moraines of the Atlantic Coastal Plain. It can occur with several types of barrens and woodland communities as part of the broadly defined ecosystem known as the Pine Barrens.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 8 feet and 195 feet.

Best Time to See

There are at least two times of the year when these forests are very interesting to visit. First, these forests provide critical habitat for migratory land birds in the fall and the best chance to see the most species and numbers occur after the passage of a cold front. Second, later in the fall after the migrant birds have left these forests and reached their non-breeding winter homes, brilliant red fall colors come alive in the dense heath layer underneath the rust colored leaves of oak trees. The heath species (blueberries and black huckleberries) ripen in the summer and become good snacks for hikers at this time of year.

Coastal Oak-Heath Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Scarlet Oak - Black Oak / Sassafras / Blue Ridge Blueberry Forest (CEGL006375)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dry Oak-Hardwood Forest (CES203.475)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Castanea dentata (American chestnut)

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak)

- Quercus ilicifolia (scrub oak, bear oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak)

- Quercus ilicifolia (scrub oak, bear oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

- Viburnum acerifolium (maple-leaved viburnum)

-

Herbs

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen, teaberry)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum (eastern bracken fern)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal oak-beech forest

(guide)

This is a hardwood forest with oaks (Quercus spp.) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia) as codominant tree species. This community occurs on dry, well-drained, loamy sand of morainal coves of the Atlantic coastal plain. Some occurrences are associated with maritime beech forest. Beech can range from nearly pure stands to as little as about 25% cover. The forest is usually codominated by two or more species of oaks, usually black oak (Quercus velutina) and white oak (Q. alba). Red oak (Quercus rubra) may be present at low density and is a key indicator species along with sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

- Coastal oak-hickory forest

(guide)

This is a hardwood forest with oaks (Quercus spp.) and hickories (Carya spp.) as codominant tree species. This community is found on dry, well-drained, loamy sand of knolls, upper slopes, or south-facing slopes of glacial moraines of the Atlantic coastal plain. Coastal oak-hickory forests are generally more species rich than Coastal oak-heath forests, and the presence of significant hickory species is the key to separating these natural community types.

- Coastal oak-holly forest

(guide)

This is a mixed deciduous-evergreen broadleaf forest that occurs on somewhat moist and moderately well drained silt and sandy loams in low areas on morainal plateaus. The elevation afforded by the raised plateau protects these areas from overwash and salt spray. In New York State, this forest is best developed on the narrow peninsulas of eastern Long Island. The trees are usually not stunted, and are removed from the pruning effects of severe salt spray. The canopy of a mature stand is usually up to about 20 m (65 ft) tall. Coastal oak-holly forests differ from coastal oak-heath forests by having a significant amount of American holly in the canopy, and by generally occurring on moister sites.

- Coastal oak-laurel forest

(guide)

This is a large patch, low diversity hardwood forest with broadleaf canopy and evergreen subcanopy that typically occurs on dry well-drained, sandy and gravelly soils on the coastal plain. The dominant tree is typically scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea) with some white oak (Q. alba), black oak (Q. velutina), and chestnut oak as well. The shrub layer is well-developed typically with a tall, often nearly continuous cover of the evergreen heath, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia).

- Pitch pine-oak-heath woodland

(guide)

This is a pine barrens community that occurs on well-drained, infertile, sandy soils in eastern Long Island (and possibly on sandy or rocky soils in upstate New York). The structure of this community is intermediate between a shrub-savanna and a woodland. It can be associated with coastal oak-heath forests, but the prominence of pitch pine and scrub oak separates this natural community from coastal oak-heath forests.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Coastal Oak-Heath Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Brodo, Irwin M. 1968. The lichens of Long Island, New York: A vegetational and floristic analysis. New York State Museum Bulletin 410: 1-330.

Busby, Posy E., C. D. Canham, G. Motzkin, and D. R. Foster. 2009. Forest response to chronic hurricane disturbance in coastal New England. Journal of Vegetation Science 20: 487-497.

Busby, Posy E., G. Motzkin and B. R. Hall. 2009. Distribution and dynamics of American beech in coastal southern New England. Northeastern Naturalist 16(2): 159-176.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 140 (4):376-382.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reiners, W.A. 1967. Relationships between vegetational strata in the pine barrens of central Long Island, New York. Bulletin Torrey Botanical Club 94(2): 87-99.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Sneddon, L. 1998. North Atlantic Coast classification. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science, Boston, MA. July 1998.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson and K. Metzler. 1996. Community alliances and elements of the eastern region. Second draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Region Conservation Science, Boston, MA. April 11. 234 pp.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson, and J. Lundgren. 1998. International classification of ecological communities: terrestrial vegetation of the northeastern United States. July 1998 working draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science and Natural Heritage ProgramS of the northeastern United States, Boston, MA. July 1998.

Spies, T.A. and M.G. Turner. 1999. Dynamic forest mosaics. Pages 95-160 in: M. L. Hunter, Jr., editor. Maintaining biodiversity in forest ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Suchy, Larry. 2006. Mast survey. Northwest Arkansas Community College. Bentonville, AK.

The President's Council on Sustainable Development. 1999. Towards a Sustainable America: Advancing Prosperity, Opportunity, and a Healthy environment for the 21st Century. Washington, DC. 97 pp. plus appendices.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coastal oak-heath forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/coastal-oak-heath-forest/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.