Marine Intertidal Gravel/Sand Beach

- System

- Marine

- Subsystem

- Marine Intertidal

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2S3

Imperiled or Vulnerable in New York - Very vulnerable, or vulnerable, to disappearing from New York, due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign either S2 or S3.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G5

Secure globally - Common in the world; widespread and abundant (but may be rare in some parts of its range).

Summary

Did you know?

The "wrack line" forms at the uppermost tide line of the marine intertidal gravel/sand beach. Here marine algae, eelgrass, shells, and other debris, are deposited at high tide. Since plants and seaweeds cannot grow in the unstable wash zone of the beach, numerous shorebirds and other animals rely on the wrack line as a food source.

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 1000 miles of marine intertidal gravel/sand beach on Long Island covering about 10,000 to 16,000 acres; there may be more than 30 to 50 extant occurrences statewide. The several documented occurrences of this community have good viability and are protected on public or private conservation land. The community is restricted to the ocean shoreline of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in Suffolk, Richmond, Queens, Kings, and Nassau Counties. Although the number of marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches may have increased slightly when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development, the overall trend for the community is declining as a result of coastal development and recreational overuse. Sea level rise may result in permanent flooding of some occurrences, especially in areas where barriers prevent the migration of beaches inland.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches have likely remained stable in recent decades, because most beach development occurs above mean high tide in the maritime beach and dune areas. However, beach viability/ecological integrity is suspected to be slowly declining, primarily due to anthropogenic alterations (both physical and hydrological) to beach/dune/swale dynamics and coastal development (e.g., fragmentation, shoreline hardening, road construction, and community destruction).

Long-term Trends

Although the number of marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches in New York may have increased from historical numbers when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development into numerous large and small stretches of beach, their aerial extent and viability are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in connectivity, hydrology, water quality, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Conservation Overview

Maintain dynamic beach and dune processes, prevent recreational overuse (driving on the beach is particularly destructive) and encourage the public to carry away all of their trash. Ensure connectivity landward to maritime beaches and dunes, and offshore toward the open ocean that allows plants and animals to freely move between these habitats. Remove shoreline armoring to increase overland sediment input; improve water quality by reducing or eliminating sewer and stormwater discharge and pesticide application; restore tidal regime by removing culverts, dikes, and impoundments, plugging ditches, and replacing static flow restriction devices with those that are calibrated for local tidal hydrology.

Threats

Threats to marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches in New York include driving on the beach at low tide (ATVs and four-wheel drive vehicles), fragmentation by development, barriers to connectivity between the open ocean and the beach/dune system, trampling, increased horseback riding, and trash. Processes that create and maintain these beaches have been disrupted by hydrologic alterations to tidal dynamics, fragmentation, shoreline hardening, altered sediment budgets, and management practices like beach replenishment. Sea level rise may result in permanent flooding of some occurrences, especially in areas where barriers prevent the migration of beaches inland.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Maintain dynamic beach and dune processes, prevent recreational overuse (driving on the beach at low tide is particularly destructive) and encourage the public to carry away all of their trash. Ocean-derived trash may be deposited in the wrackline at some locations. Ensure connectivity between maritime dunes, maritime beaches, and the open ocean to allow seed dispersal and to enable species to freely move between habitats during nesting season. Remove shoreline armoring to increase overland sediment input; improve water quality by reducing or eliminating sewer and stormwater discharge and pesticide application; restore tidal regime by removing culverts, dikes, and impoundments, plugging ditches, and replacing static flow restriction devices with those that are calibrated for local tidal hydrology.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Minimize or eliminate hardened shoreline and avoid dumping dredge spoil onto marine intertidal beaches. This community is best protected as part of a larger ocean shoreline ecosystem. Protected areas should encompass nearshore marine communities, such as marine rocky intertidal and marine eelgrass meadows if present, as well as onshore maritime communities, such as maritime beach, dunes, and bluffs if present. Connectivity should be maintained in both directions, on- and offshore. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Similarly, fragmentation of linear beaches should be avoided. Bisecting roads and developments significantly disrupt biota and alter physical beach processes.

Inventory Needs

Surveys and documentation of additional occurrences are needed, as are data on rare and characteristic animals, especially benthic invertebrates.

Research Needs

Future research on marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches should include monitoring community response to sea level rise, sediment starvation, and permanent flooding and studying nutrient exchange processes and relationships to adjacent maritime communities above high tide.

Rare Species

Range

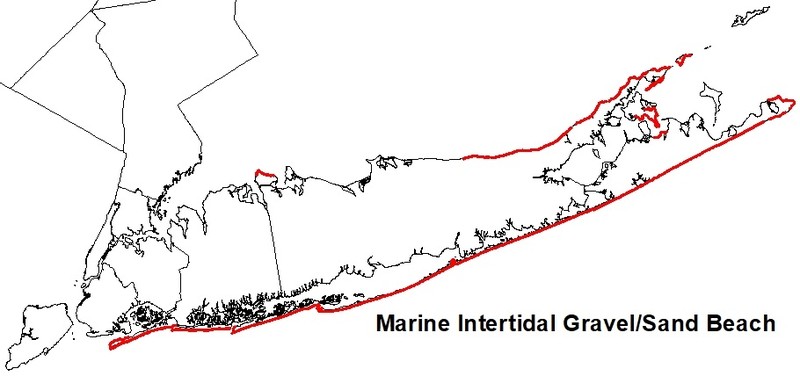

New York State Distribution

This community is restricted to the ocean shoreline with sand or gravel substrate of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in Suffolk, Richmond, Queens, Kings, and Nassau Counties

Global Distribution

This community ranges along the Atlantic Coast from southern Maine to North Carolina.

Best Places to See

- Jones Beach State Park (Nassau County)

- Montauk Point State Park (Suffolk County)

- Orient Beach State Park (Suffolk County)

- Gateway National Recreation Area - Jacob Riis Park (Queens County)

- Caumsett State Park (Suffolk County)

- Fire Island National Seashore (Sullivan County)

Identification Comments

General Description

The marine intertidal gravel/sand beach is a community washed by rough, high-energy waves, with sand or gravel substrates that are well-drained at low tide. These areas are subject to high fluctuations in salinity and moisture, but generally the sand is noticeably wetter than the adjacent maritime beach sand. A relatively low diversity community, it is perhaps best characterized by the benthic invertebrate fauna including polychaetes (Spiophanes bombyx, Pygospio elegans, Clymenella torquata, Scoloplos fragilis, Nephtys incisa), amphipods (Protohaustorius deichmannae, Acantho¬haustorius millsi), and mole crabs (Emerita spp.). This community provides feeding grounds for migrant shorebirds, such as sanderling (Calidris alba) and semipalmated plover (Charadrius semipalmatus), and breeding shorebirds, such as piping plover (Charadrius melodus).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

These areas are subject to high fluctuations in salinity and moisture, but generally the sand is noticeably wetter than the adjacent maritime beach sand and located below the wrack line.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between -2 feet and 35 feet.

Best Time to See

Marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches are scenic year-round! Enjoy a visit in the middle of the summer when the ocean is warm for swimming.

Marine Intertidal Gravel/Sand Beach Images

Classification

Characteristic Species

-

Nonvascular plants

- Calothrix sp.

-

Unvegetated

- amphipod (Acantho¬haustorius millsi)

- amphipod (Protohaustorius deichmannae)

- mole crabs (Emerita spp.).

- polychaete (Clymenella torquata)

- polychaete (Nephtys incisa)

- polychaete (Pygospio elegans)

- polychaete (Scoloplos fragilis)

- polychaete (Spiophanes bombyx)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Marine intertidal mudflats

(guide)

Marine intertidal mudflat substrates are composed of silt or sand that is rich in organic matter and poorly drained at low tide. Mudflats are usually adjacent to low salt marshes and saltwater tidal creeks. Whereas, marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches are composed of sand or gravel substrates that are well-drained at low tide; and they are usually adjacent to maritime beaches.

- Marine rocky intertidal

(guide)

Marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches have sand or gravel substrates that are well-drained at low tide and they are largely unvegetated. Whereas, marine rocky intertidal communities occur on rocky shores that are washed by rough, high-energy ocean waves and dominated by attached marine algae and marine fauna.

- Maritime beach

(guide)

Marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches are marine communities that are fully exposed at low tide and extend inland to the limit of mean high tide. Maritime beaches are terrestrial and are located in a band just above this tidal limit.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Marine Intertidal Gravel/Sand Beach. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., A. L. Feldmann, T. G. Howard, J. J. Schmid, E. Eastman, E. Largay, and L. A. Sneddon. 2008. Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Gateway National Recreation Area. Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2008/107. National Park Service. Northeast Region. Philadelphia, PA.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, G. J., E. S. Runnells, and T. G. Howard. 2019. Montauk Point, Marine Rocky Intertidal Monitoring, Year One 2018 Baseline Results. New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany, NY.

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Gregory J. Edinger

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Marine intertidal gravel/sand beach.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/marine-intertidal-gravelsand-beach/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.