Maritime Beach

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G5

Secure globally - Common in the world; widespread and abundant (but may be rare in some parts of its range).

Summary

Did you know?

Maritime beaches and dunes provide important nesting ground for birds such as piping plover, least tern, common tern, and roseate tern.

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 1000 miles of maritime beach on Long Island covering about 10,000 to 16,000 acres; there may be more than 30 to 50 extant occurrences statewide. The several documented occurrences of this community have good viability and are protected on public or private conservation land. The community is restricted to the ocean shoreline of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in Suffolk, Richmond, Queens, Kings, and Nassau Counties. Although the number of maritime beaches may have increased slightly when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development, the overall trend for the community is declining as a result of coastal development and recreational overuse. Sea level rise may result in permanent flooding of some occurrences, especially in areas where barriers prevent the migration of beaches inland.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of maritime beaches have likely declined in recent decades, because beach development occurs above mean high tide in the maritime beach and dune areas. However, beach viability/ecological integrity is suspected to be slowly declining, primarily due to anthropogenic alterations (both physical and hydrological) to beach/dune/swale dynamics and coastal development (e.g., fragmentation, shoreline hardening, road construction, and community destruction).

Long-term Trends

Although the number of maritime beaches in New York may have increased substantially from historical numbers when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development into numerous large and small stretches of beach, their aerial extent and viability are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in connectivity, hydrology, water quality, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to maritime beaches in New York include driving on the beach (ATVs and four-wheel drive vehicles), fragmentation by development, barriers to connectivity between the open ocean and the beach/dune system, trampling, increased horseback riding, trash, and invasion by exotic species, including winged pigweed (Cycloloma atriplicifolium) and Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculata). Processes that create and maintain maritime beaches have been disrupted by hydrologic alterations to tidal dynamics, fragmentation, shoreline hardening, altered sediment budgets, and management practices like beach replenishment. Sea level rise may result in permanent flooding of some occurrences, especially in areas where barriers prevent the migration of beaches inland.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Maintain dynamic beach and dune processes, prevent recreational overuse (driving on the beach is particularly destructive) and encourage the public to carry away all of their trash. Monitor rare plant and animal populations, including seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus) and beach-dune tiger beetle (Cicindela hirticollis), and the nesting use of beaches by species such as the horseshoe crab and the piping plover. Take measures (e.g., install fencing and predator exclosures) to prevent disturbance to critical areas. Ensure connectivity between maritime dunes, maritime beaches, salt marshes, and the open ocean to allow seed dispersal and to enable species to freely move between habitats during nesting season. Remove shoreline armoring to increase overland sediment input; improve water quality by reducing or eliminating sewer and stormwater discharge and pesticide application; restore tidal regime by removing culverts, dikes, and impoundments, plugging ditches, and replacing static flow restriction devices with those that are calibrated for local tidal hydrology.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Minimize or eliminate hardened shoreline and avoid dumping dredge spoil onto maritime beaches. This community is best protected as part of a large salt marsh complex. Protected areas should encompass the full mosaic of low salt marsh, high salt marsh, marine intertidal mudflats, saltwater tidal creek, salt panne, and salt shrub communities to allow dynamic ecological processes (sedimentation, erosion, tidal flushing, and nutrient cycling) to continue. Connectivity to estuarine, brackish, and freshwater tidal communities; upland dunes; and shallow offshore communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Similarly, fragmentation of linear beaches should be avoided. Bisecting roads and developments significantly disrupt biota and alter physical dune processes.

Inventory Needs

Surveys and documentation of additional occurrences are needed, as are data on rare and characteristic animals.

Research Needs

Future research on maritime beaches should include monitoring community response to sea level rise, sediment starvation, and permanent flooding and studying nutrient exchange processes and relationships to adjacent communities (e.g., salt marsh complexes and maritime dunes).

Rare Species

- Amaranthus pumilus (Seabeach Amaranth) (guide)

- Atriplex dioica (Thick-leaved Orach) (guide)

- Carex hormathodes (Marsh Straw Sedge) (guide)

- Cenchrus tribuloides (Dune Sandspur) (guide)

- Charadrius melodus (Piping Plover) (guide)

- Cicindela hirticollis (Hairy-necked Tiger Beetle) (guide)

- Egretta thula (Snowy Egret) (guide)

- Erechtites hieraciifolius var. megalocarpus (Coastal Fireweed) (guide)

- Eupatorium pubescens (Hairy Thoroughwort) (guide)

- Gelochelidon nilotica (Gull-billed Tern) (guide)

- Nyctanassa violacea (Yellow-crowned Night-Heron) (guide)

- Polygonum buxiforme (American Knotweed) (guide)

- Polygonum glaucum (Seabeach Knotweed) (guide)

- Rumex fueginus (American Golden Dock) (guide)

- Rynchops niger (Black Skimmer) (guide)

- Sesuvium maritimum (Sea Purslane) (guide)

- Sterna dougallii (Roseate Tern) (guide)

- Sterna hirundo (Common Tern) (guide)

- Sternula antillarum (Least Tern) (guide)

- Suaeda linearis (Southern Sea Blite) (guide)

- Sympistis perscripta (Scribbled Sallow Moth) (guide)

- Sympistis riparia (Dune Sympistis) (guide)

Range

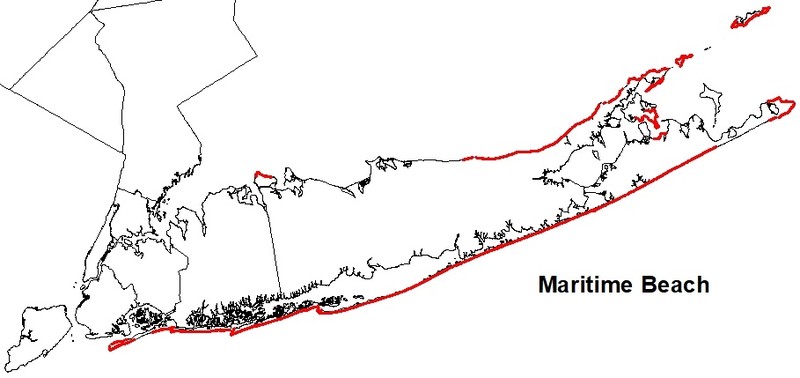

New York State Distribution

This community is restricted to the ocean shoreline of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in Suffolk, Richmond, Queens, Kings, and Nassau Counties.

Global Distribution

This community ranges along the Atlantic Coast from southern Maine to North Carolina (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Jones Beach State Park (Nassau County)

- Montauk Point State Park (Suffolk County)

- Orient Beach State Park (Suffolk County)

- Gateway National Recreation Area - Jacob Riis Park (Queens County)

- Caumsett State Park (Suffolk County)

- Fire Island National Seashore (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A community with extremely sparse vegetation that occurs on unstable sand, gravel, or cobble ocean shores above mean high tide, where the shore is modified by storm waves and wind erosion. The upper margin of a maritime beach often grades into the base of a primary maritime dune, or other maritime community, such as maritime shrubland or one of the maritime forests.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic species include beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), sea-rocket (Cakile edentula ssp. edentula), seaside atriplex (Atriplex patula), seabeach atriplex (A. arenaria), seabeach sandwort (Honckenya peploides), salsola (Salsola kali), seaside spurge (Chamaesyce polygonifolia), seabeach knotweed (Polygonum glaucum), and seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between -1 feet and 32 feet.

Best Time to See

Maritime beaches are scenic year-round! Enjoy a visit in the middle of the summer when the ocean is warm for swimming.

Maritime Beach Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- American Searocket - Seaside Sandmat Sparse Beach Vegetation (CEGL004400)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Sandy Beach (CES203.301)

Characteristic Species

-

Vines

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Amaranthus pumilus (sea-beach amaranth, coast amaranth)

- Ammophila breviligulata (beach grass)

- Anaphalis margaritacea (pearly everlasting)

- Atriplex patula (spear orach)

- Cakile edentula var. edentula (American sea rocket)

- Datura stramonium (Jimsonweed, common thorn-apple)

- Lathyrus japonicus var. maritimus (beach-pea)

- Oenothera biennis (common evening-primrose)

- Oxybasis rubra var. rubra (red-pigweed)

- Polygonum glaucum (sea-beach knotweed)

- Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium (fragrant rabbit-tobacco)

- Salsola kali ssp. kali (northern saltwort)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Marine intertidal gravel/sand beach

(guide)

Marine intertidal gravel/sand beaches are marine communities that are fully exposed at low tide and extend inland to the limit of mean high tide. Maritime beaches are terrestrial and are located in a band just above this tidal limit.

- Marine rocky intertidal

(guide)

While both communities can occur on rocky substrate along the ocean shoreline, marine rocky intertidal communities are washed by rough, high-energy ocean waves and are dominated by attached marine algae and fauna. They are exposed at low tide and extend inland to the limit of mean high tide. Whereas, maritime beaches are very sparsely vegetated, or unvegetated, terrestrial communities that are located in a band just above this tidal limit and the substrate is more often sand.

- Sand beach

Sand beaches are similar, structurally, to maritime beaches but they occur on the unstable sandy shores of large freshwater lakes instead of on the maritime coast.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Beach. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Art, H. W. 1976. Ecological studies of the Sunken Forest, Fire Island National Seashore, New York. National Park Service Scientific Monograph Series No. 7, Publication No. NPS 123. 237 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Johnson, Anne F. 1985. A guide to the plant communities of the Napeague dunes Long Island, New York. Mad Printers, Mattituck, New York. 58 pp.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Schlesinger, M.D., E.L. White, S.M. Young, G.J. Edinger, K.A. Perkins, N. Schoppmann, and D. Parry. 2016. Biodiversity Inventory of Plum Island, New York. New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany, New York, and SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

Significant Habitat Unit. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. No date. Significant Habitat data.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime beach.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-beach/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.