Maritime Oak Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2S3

Imperiled or Vulnerable in New York - Very vulnerable, or vulnerable, to disappearing from New York, due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign either S2 or S3.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Post oak (Quercus stellata), a dominant canopy species of maritime oak communities occurs at the northern part of its range in New York. The common name of this tree comes from the fact that it is rot resistent in soil and thus has been used widely for the construction of fence posts. The specific epithet, "stellata," refers to the stellate, or star-like radiating hairs on the under side of the leaves. These hairs can be observed if the leaves are examined with a hand lens.

State Ranking Justification

There are about 50 to 100 occurrences on Long Island. A few documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has a very limited distribution in the state and includes a couple large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to coastal development pressure.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of maritime oak forests in New York have probably declined moderately in recent decades as a result of clearing for agriculture and other coastal development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of maritime oak forests in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with clearing for agiculture and other coastal development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to maritime oak forests include changes in land use (e.g., clearing for development, excessive logging), forest fragmentation (e.g., roads, railroads), and invasive plant species. Other threats may include over-browsing by deer, recreational overuse (e.g., trails, ATVs, horses), and trash dumping. The loss of maritime influence (e.g., salt spray, sand deposition, etc.) may alter the structure and composition of this community and threaten its long-term viability.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. Encourage selective logging in areas that are under active forestry.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those developments built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Inventory any remaining large examples on Long Island. Continue searching for large sites in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research composition of maritime oak forests on Long Island in order to characterize variations and clearly separate from them other maritime forest types. Collect sufficient plot data in order to fully document known occurrences. More data are needed before the three topo-edaphic variants can be distinguished as separate types: post oak-catbrier forest variant, post oak-basswood forest variant, post oak-blackjack oak forest variant.

Rare Species

Range

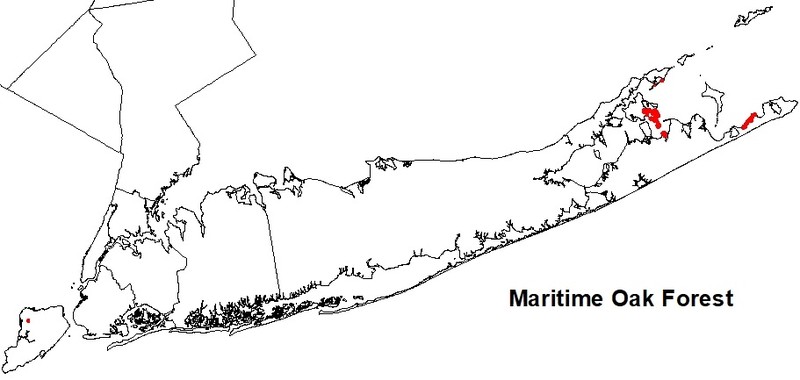

New York State Distribution

This community is restricted to the maritime portion of the Atlantic Coastal Lowlands region. Known examples range from Shelter Island, South Dumpling Island and Peconic Dunes, west to Staten Island. Occurrences are concentrated on islands and necks in the Peconic Bay and along the eastern half of the north shore of Long Island bordering Long Island Sound. Small maritime oak forests occur farther west along the north shore of Long Island. These forests are also found on the south shore of Long Island along Montauk Peninsula with smaller examples likely occurring farther west.

Global Distribution

Maritime post oak forest is currently known from Long Island, New York, and Connecticut. It possibly occurs in New Jersey.

Best Places to See

- Hither Hills State Park (Suffolk County)

- Sag Harbor State Park (Suffolk County)

- Orient Beach State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Maritime oak forest communities occur very near to the ocean shore, often within 200 m, on the edges of salt marshes or on exposed bluffs. The canopy is dominated by oak species (Quercus alba, Q. coccinea, and Q. veluntina), and contains post oak (Q. stellata). The trees, particularly on the most exposed edges of the forest community, may be stunted, flat-topped, and multi-stemmed, due to the influences of high winds and salt spray from the nearby shoreline. The understory is often dense, with a thicket of briers (Smilax glauca, S. rotundifolia), bayberry (Myrica pensylvancia), black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), and saplings of black cherry (Prunus serotina). The herbaceous layer is sparse, and often dominated by wavy hair grass (Deschampsia flexuosa).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

An oak-dominated forest, that borders salt marshes or occurs on exposed bluffs and sand spits within 200 m of the ocean. Trees closest to the shore are often stunted, flat-topped, and multi-stemmed due to the stresses of high winds and salt spray. The understory is dense, sometimes forming a thicket of briers, bayberry, black huckleberry and black cherry saplings.

Best Time to See

During the growing season, a common shrub of martime oak communities, bayberry, produces spicy-smelling fruit. These berries persist on the branches, and can be observed throughout much of the year.

Maritime Oak Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Post Oak - Black Oak / Northern Bayberry / Wavy Hairgrass Forest (CEGL006373)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.302)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Amelanchier canadensis var. canadensis (coastal shadbush)

- Carya tomentosa (mockernut hickory)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus stellata (post oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Amelanchier canadensis var. canadensis (coastal shadbush)

- Quercus marilandica var. marilandica (blackjack oak)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

- Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum (smooth arrowwood)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Quercus ilicifolia (scrub oak, bear oak)

- Rosa carolina ssp. carolina (eastern pasture rose)

-

Tree saplings

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Vines

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Smilax glauca (white-leaved greenbrier)

- Smilax rotundifolia (common greenbrier)

-

Herbs

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Carex swanii (Swan's sedge)

- Panicum virgatum (switch grass)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal oak-heath forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-heath forest communities occur on sandy loam soils, further from the ocean shore, and away from the influences of salt spray and high winds that shape maritime forest communities. The canopy of coastal oak-heath forest communities, like maritime post oak communities, is dominated by oak species, but the understory is dominated by low heath shrubs (i.e., Vaccinium spp., Gaylussacia baccata), rather than the thicket of briers of maritime forest types.

- Coastal oak-hickory forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-hickory forest communities occur on sandy loam soils, further from the ocean shore, and away from the influences of salt spray and high winds that shape maritime forest communities. In addition, the canopy of coastal oak-hickory forest communities has signficant cover of hickories (Carya alba, C. glabra, C. ovalis), and the understory is dominated by a variety of low shrubs (e.g., Vaccinium spp., Gaylussacia baccata, Viburnum acerfolium), rather than the thicket of briers of maritime forest types.

- Maritime beech forest

(guide)

Maritime beech forests, like maritime post oak forests, may occur on exposed bluffs on sandy soils, but maritime beech forests have American beech (Fagus grandiflora) as the dominant canopy species. Oak species may be present with red maple (Acer rubrum) in low densities. Maritime post oak communities are dominated by oak species and include post oak as a canopy component.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Oak Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 140 (4):376-382.

Hunt, David M. 1997. "Quercus stellata-Q. marilandica forest" entity in New York. Unpublished momorandum. April. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 1 p.

Lamont, E. 1997. The maritime oak-basswood forest on Long Island's north fork. Long Island Botanical Society Newsletter. 7(5):27-28.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Rosza, R. and K. Metzler. 1982. Plant communities of Mashomack. In: The Mashomack Preserve Study. Vol. 2: Biological Resources. S. Englebright, ed. The Nature Conservancy, East Hampton, New York.

Taylor, Norman. 1923. The vegetation of Long Island, Part I. The vegetation of Montauk: A study of grassland and forest. Memoirs Brooklyn Botanical Garden. 2:1-107.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Jennifer Garret

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime oak forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-oak-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.