Maritime Red Cedar Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Eastern prickly-pear (Opuntia humifusa) is the only member of the cactus family that is found in the northeastern states. It is found in a variety of habitats and is tolerant of extreme conditions, including the salt spray and wind influence of maritime red cedar forests. However, it is shade intolerant, and can be crowded out by the increasing canopy cover of forests. New York's only native cactus is often associated with red cedar. Interestingly, it grows in maritime red cedar forests on Long Island and red cedar rocky summits in the Hudson Valley.

State Ranking Justification

There are very few occurrences of maritime red cedar forests in New York State. The only examples come from Suffolk County, Long Island. These occurrences are usually small and vulnerable to disturbance or destruction from development, wood-cutting or post-cutting, and off-road vehicle (ORV) abuse. Most of the known occurrences are on publicly owned property but need more protection.

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of maritime red cedar forests in New York have probably declined slightly in recent decades due to development, fire suppression, and disturbance by off-road vehicles (ORVs).

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of maritime red cedar forests in New York have probably had large declines from historical numbers due to the settlement and development of the area, fire suppression, and fragmentation.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The greatest threats to the maritime red cedar forest are commercial and residential development and recreational overuse. Development not only causes a reduction in the overall size of the forest but also the fragmentation of the forest into smaller units. The increased use of off-road vehicles (ORVs) causes erosion, fragmentation of the forest, and acts as a corridor for the invasion of exotic species. Presently, most of the ORV use is on the seaward edges of the community. Other threats include over-browsing by deer on seedlings and saplings which threatens the regeneration of forest canopy trees.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine & French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. Other management considerations are: avoid cutting old growth examples, monitor for off road vehicle (ORV) abuse, control exotic and invasive species including the removal of black pine (Pinus nigra), and provide signage to make sure that visitors stay on trails.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Soils are sandy in and around this community and the effect of clearing and construction on soil retention and erosion must be considered during any development activities. Similarly, these sandy soils are nutrient-poor and any soil enrichment activities (septic leach fields, fertilized lawns, etc.) have a high probability of altering community structure and function.

Inventory Needs

Survey for and document additional sites for this natural community type. Need additional surveys at known locations to develop complete plant and animal species lists. In addition, detailed plot data is needed at known locations and any new sites that are found.

Research Needs

Research is needed to better define the composition of maritime and/or dune forests on Long Island in order to characterize variations between them. Collect sufficient plot data to support this classification. Locate other occurrences of maritime red cedar forests.

Rare Species

Range

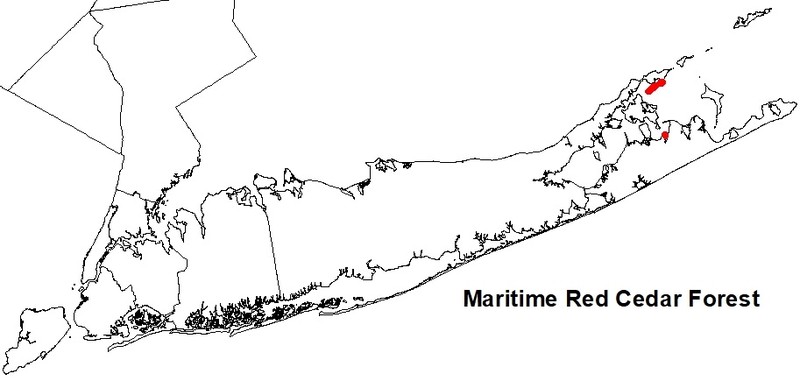

New York State Distribution

Maritime red cedar forests are currently found only on the shores of the coastal plain of Long Island within the zone influenced by salt spray. There are very few occurrences of this community type currently documented.

Global Distribution

This maritime forest to woodland community dominated by red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) occurs on sand dunes, upper edges of salt marshes, and less commonly on rocky headlands of the northern and mid-Atlantic coast. This maritime forest to woodland community is naturally restricted to major coastal dune systems. An estimated 30 occurrences of this community type exist, ranging in size from less than an acre up to a maximum of 100, with an average size of less than 10 acres. This association occurs along the northern and mid-Atlantic coast from Virginia to Massachusetts and possibly up to Maine and Quebec (NatureServe Explorer 2009).

Best Places to See

- Orient Beach State Park (Suffolk County)

- Fire Island National Seashore (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

This maritime forest to woodland community occurs on sand dunes and is dominated by eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana). The physiognomy of this association is variable, ranging from dense tall-shrub thickets, to open woodlands, to closed canopy forest; trees are generally shorter than 4 m. Canopy trees are stunted and salt-pruned. Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) may form pure stands and is present in all tree and shrub layers. Other characteristic trees include post oak (Quercus stellata) and black cherry (Prunus serotina). Shrubs and vines include bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), groundsel-tree (Baccharis halimifolia), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). Herb species include eastern prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa), common hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), switch grass (Panicum virgatum), and seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A conifer forest to woodland that occurs on dry sites near the ocean. Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) is the dominant tree, often forming nearly pure stands. Red cedar is usually present in all tree and shrub layers. Other characteristic trees include post oak (Quercus stellata) and black cherry (Prunus serotina).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 5 feet and 7 feet.

Best Time to See

This maritime red cedar forest is probably best seen in September and October when the bluish-black berry-like fruit ripens and migrating birds such as Cedar Waxwing can be seen devouring the berries.

Maritime Red Cedar Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Eastern Red-cedar / Northern Bayberry Woodland (CEGL006212)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.302)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Quercus stellata (post oak)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Baccharis halimifolia (groundsel-tree)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

-

Vines

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Opuntia humifusa (eastern prickly-pear)

- Panicum virgatum (switch grass)

- Schizachyrium scoparium var. scoparium (little bluestem)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Maritime beech forest

(guide)

This is a hardwood forest with American beech (Fagus grandifolia) dominant that usually occurs on north-facing exposed bluffs and the back portions of rolling dunes in well-drained fine sands. Black oak (Quercus velutina) and red maple (Acer rubrum) may be present at low density. Red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), if present, is generally only in small amounts within this natural community.

- Maritime holly forest

(guide)

This is a broadleaf evergreen maritime strand forest that occurs in low areas on the back portions of maritime dunes. The dunes protect these areas from overwash and salt spray enough to allow forest formation. In New York State, this forest is best developed and probably restricted to the barrier islands off the south shore of Long Island. The trees are usually stunted and flat-topped because the canopies are pruned by salt spray and exposed to winds. The dominant tree is usually American holly (Ilex opaca), but typically includes a few hardwood trees such as sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier sp.), and oak (Quercus sp.). Red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), if present within this natural community, occurs in only small amounts.

- Maritime post oak forest

(guide)

This is an oak-dominated forest that borders salt marshes or occurs on exposed bluffs and sand spits within about 200 meters of the seacoast. The trees may be somewhat stunted and flat-topped because the canopies are pruned by salt spray and exposed to winds. The forest is usually dominated by two or more species of oaks. Characteristic canopy trees include post oak (Quercus stellata), black oak (Q. velutina), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea) and white oak (Q. alba). A small number of eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) may be present, but is not a dominant tree in any strata within maritime post oak forests.

- Successional maritime forest

(guide)

This is a successional hardwood forest that occurs in low areas near the seacoast. This forest is a variable type that develops after vegetation has burned or land has been cleared (such as pastureland or farm fields). The trees may be somewhat stunted and flat-topped because the canopies are pruned by salt spray. The forest may be dominated by a single species, or there may be two or three codominants. Successional maritime forests that have red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) as a dominant tree will likely succeed to a maritime red cedar forest upon maturity.

- Successional red cedar woodland

This is a woodland community that commonly occurs on abandoned agricultural fields and pastures, usually at elevations less than 1000 ft (305 m). The dominant tree is eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), which may occur widely spaced in young stands and may be rather dense in more mature stands. Smaller numbers of gray birch (Betula populifolia), hawthorn (Crataegus spp.), buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), and other early successional hardwoods may be present. Shrubs and groundlayer vegetation are similar to a successional old field.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Clark, James. 1986. Coastal forest tree populations in a changing environment, southeastern Long Island, New York. Ecological Monographs 56(3): 259-277.

Conard, H.S. 1935. The plant associations of central Long Island. American Midland Naturalist 16:433-515.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Greller, A. M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 104:376-382.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Lamont, E. and R. Stalter. 1991. The vascular flora of Orient Beach State Park, Long Island, New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 118(4): 459-468.

Latham, Roy. 1935. Flora of the State Park, Orient, Long Island, New York. Torreya 34:139-149.

Lundgren, J. 2000. Lower New England - Northern Piedmont Ecoregion Forest Classification. The Nature Conservancy, Conservation Science, Boston, MA. 72 pp.

Martin, W. E. 1959b. The vegetation of Island Beach State Park, New Jersey. Ecological Monographs 29:1-46.

Miller, S. G., S. P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Robichaud, B. and M.F. Buell. 1973. Vegetation of New Jersey: A study of landscape diversity. Rutgers Univ. Press. New Brunswick, NJ. 340 pp.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Shereen Brock

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime red cedar forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-red-cedar-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.