Successional Maritime Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

How does salt spray affect plant growth? Salt water is hypertonic for most plant cells. The salt in the salt spray will cause water to be drawn out of the plant cells causing the cells to shrink and die. The higher the concentration of salt, the faster the plant dies. This could cause the tree to be stunted as their canopy dies back from the salt spray or they could grow asymmetrically with the oceanside of the trees dying back and the side furthest from the ocean continuing to grow. Some plants growing near the ocean are actually adapted to the salt spray and can tolerate these conditions better than other plants. Bayberry is an example of this type of plant.

State Ranking Justification

There are less than 3 documented occurrences of this natural community type in New York State. It is predicted that there is the potential for possibly less than 80 total occurrences many of which would be very small in size (acreage) with the total acreage predicted to be less than 400. This maritime forest community is restricted in range to the coastal area of New York on Long Island. The potential habitat of this community is also restricted to areas directly affected by maritime processes, e.g., salt spray and winds. These areas in New York continue to be under significant threat from numerous invasive plants and development.

Short-term Trends

The acreage, extent, and condition of successional maritime forests in New York is probably stable due to the dynamic nature of successional forests in general. As farmland is abandoned or after a mature forest is burned, there will be an increase in the acreage of these successional forest types. Succession would lead to other types of maritime forests however the natural process of salt spray would maintain the community as it is. Large catastrophic events such as storms or human disturbance such as burning or clearing would revert the area back to an earlier successional type. This is a large, intact, slowly succeeding forest, recovering well from historical clearings and with good diversity of successional stages and only minor disturbances. The community is in a landscape relatively large and intact for the coastal region.

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of successional maritime forests in New York has probably declined over the long-term. These declines were due to the settlement of the area and the subsequent loss of forests due to agricultural, residential and commercial development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The threats to successional maritime forests include invasive species, development pressure,and deer browse. An increase in residential and commercial development causes fragmentation of the natural forest and a decrease in the size of the forest block into smaller and smaller units. Development and new roads also increase the potential for the invasion of exotic species that will out compete the native ones. These forests can also experience excessive deer browse on seedlings and saplings that can prevent the regeneration and establishment of mature forest trees.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

To promote a dynamic forest mosaic, allow natural processes, including gap formation from blowdowns and tree mortality as well as in-place decomposition of fallen coarse woody debris and standing snags, to operate (Spies and Turner 1999). Generally, management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. The natural maritime influence should be maintained including salt spray. Management efforts should focus on the control or local eradication of invasive exotic plants and the reduction of white-tailed deer densities. Consider deer exclosures or population management, particularly if studies confirm that canopy species recruitment is being affected by heavy browse. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that tree and shrub seedlings are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Fragmentation of coastal forests should be avoided. It is also important to maintain connectivity with adjacent natural communities not only to allow nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but to allow animals to move between them seasonally. Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Additional inventory is needed to confirm the extent of this community type and to map the least disturbed cores. It would also be useful to map and identify salt spray areas. Inventory and plots are also needed to improve the species lists (both plant and animal) and to better document the natural community.The spread of invasive species also needs to be monitored.

Research Needs

Research is needed to document the successional trend to a mature forest type and the impact of deer browse.

Rare Species

Range

New York State Distribution

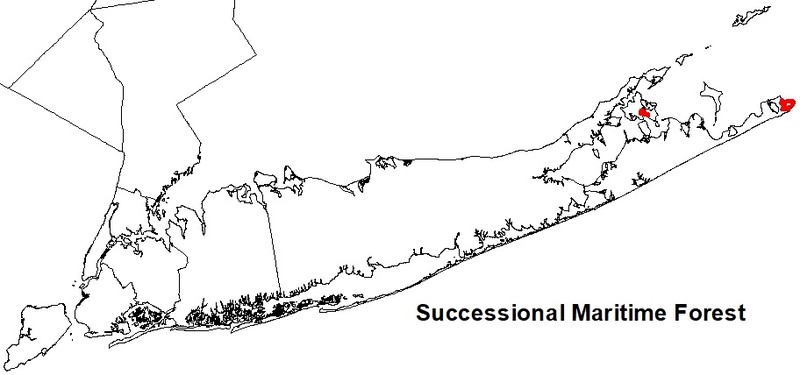

This natural community is restricted to maritime portion of the coastal lowlands region. The forest occurs on sheltered backdunes, bluffs, or more interior coastal areas not directly influenced by overwash but affected by salt spray and wind-pruning. Known examples range from Caswell Cliff on Montauk Point, west to Friars Head on the North Shore of Long Island and Sunken Forest on the South Shore of Long Island. Other examples are expected as far west as the Tottenville area of Staten Island and bordering the bays at the western headwaters of Long Island Sound.

Global Distribution

These forests occur along the North Atlantic Coast from Delaware to New Hampshire with the possibility of occuring further north into Maine.

Best Places to See

- Mashomack Preserve (Suffolk County)

- Sanctuary State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

This is a successional hardwood forest that occurs in low areas near the seacoast. This forest is a variable type that develops after vegetation has burned or land cleared (such as pastureland or farm fields). The trees may be somewhat stunted and flat-topped because the canopies are pruned by salt spray. The forest may be dominated by a single species, or there may be two or three codominants.This forest represents an earlier seral stage of other maritime forests, such as maritime post oak forest, maritime holly forest, maritime red cedar forest, and probably others. Soil and moisture regime will usually determine which forest type succeeds from this community. A few disturbance-climax examples occur, maintained by severe and constant salt spray.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Successional maritime forests are areas of abandoned farmland or occur after vegetation has been burned or land cleared. These forests are generally in immediate proximity to marine communities and will occur as narrow "strand" communities that may not be more than 50 meters wide. Species composition will vary based on site characteristics and land history. Characteristic canopy trees include black oak (Quercus velutina), post oak (Quercus stellata), serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), white oak (Quercus alba), black cherry (Prunus serotina), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), and red maple (Acer rubrum). A small number of eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) may be present.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 5 feet and 105 feet.

Best Time to See

The fall season brings migrating landbirds to this natural community, sometimes in great numbers and species following the passage of a northwest cold front, and the birds take advantage of the cover and food opportunities that remain due to the extended growing season of coastal habitats.

Successional Maritime Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Canadian Serviceberry - Viburnum species - Northern Bayberry Scrub Forest (CEGL006379)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.302)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Amelanchier canadensis var. canadensis (coastal shadbush)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Nyssa sylvatica (black-gum, sour-gum)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus stellata (post oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Amelanchier canadensis var. canadensis (coastal shadbush)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Rosa multiflora (multiflora rose)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum (smooth arrowwood)

-

Vines

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Smilax glauca (white-leaved greenbrier)

- Smilax rotundifolia (common greenbrier)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

- Vitis riparia (river grape, frost grape)

-

Herbs

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Danthonia spicata (poverty grass)

- Dichanthelium clandestinum (deer-tongue rosette grass)

- Erechtites hieraciifolius var. hieraciifolius (common pilewort)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Rubus phoenicolasius (wineberry)

- Solidago rugosa var. rugosa (common wrinkle-leaved goldenrod)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Maritime post oak forest

(guide)

This is an oak-dominated forest that borders salt marshes or occurs on exposed bluffs and sand spits within about 200 meters of the seacoast. The trees may be somewhat stunted and flat-topped because the canopies are pruned by salt spray and exposed to winds. This forest is usually dominated by two or more species of oak.

- Maritime red cedar forest

(guide)

This is a conifer forest that occurs on dry sites near the ocean. Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) is the dominant tree, often forming nearly pure stands. Red cedar is usually present in all tree and shrub layers. Other characteristic trees include post oak (Quercus stellata) and black cherry (Prunus serotina). Maritime red cedar forests differ from successional maritime forests in that they contain less successional and pioneer species, and are dominated by red cedar.

- Maritime shrubland

(guide)

This is a shrubland community that occurs on dry seaside bluffs and headlands that are exposed to onshore winds and salt spray. This community typically occurs as a tall shrubland (2-3 m), but may include areas under 1m shrub height, to areas with shrubs up to 4 m tall forming a shrub canopy in shallow depressions. These low areas may imperceptibly grade into shrub swamp if soils are sufficiently wet. Trees are usually sparse or absent (ideally less than 25% cover). Maritime shrublands differ from successional maritime forests in that they usually have much less than 25% cover of trees, but maritime shublands may form a patchy mosaic and grade into other maritime communities. For example, if trees become more prevalent it may grade into one of the maritime forest communities, such as successional maritime forest.

- Successional red cedar woodland

This is a woodland community that commonly occurs on abandoned agricultural fields and pastures, usually at elevations less than 1,000 ft (305 m). The dominant tree is eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), which may occur widely spaced in young stands and may be rather dense in more mature stands. This natural community is not influenced by maritime processes.

- Successional shrubland

This is a shrubland that occurs on sites that have been cleared (for farming, logging, development, etc.) or otherwise disturbed. This community has at least 50% cover of shrubs and can grade into successional forest types such as successional northern hardwoods, and successional southern hardwoods. This community is not typically influenced by maritime processes. Characteristic shrubs include gray dogwood (Cornus racemosa), eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), raspberries (Rubus spp.), hawthorne (Crataegus spp.), shadbushes (Amelanchier spp.), choke-cherry (Prunus virginiana), wild plum (Prunus americana), sumac (Rhus glabra, R. typhina), nanny-berry (Viburnum lentago), arrowwood (Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

- Successional southern hardwoods

This is a hardwood or mixed forest that occurs on sites that have been cleared or otherwise disturbed. Southern indicator species found include American elm (Ulmus americana), white ash (Fraxinus americana), red maple (Acer rubrum), and box elder (Acer negundo). Certain exotic species are commonly found in successional forests, including black locust (Robinia pseudo-acacia), tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), and buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). Any of these may be dominant or codominant in a successional southern hardwood forest. This is a broadly defined community and several seral and regional variants are known.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Successional Maritime Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Clark, J.S. 1986. Dynamism in the barrier-beach vegetation of Great South Beach, New York. Ecological Monographs 56(2):97-126.

Clark, J.S. 1986. Vegetation and land-use history of the William Floyd Estate, Fire Island National Seashore, Long Island, New York. USDI, National Park Service, North Atlantic Region, Office of Scientific Studies. 126 pp.

Clark, James. 1986. Coastal forest tree populations in a changing environment, southeastern Long Island, New York. Ecological Monographs 56(3): 259-277.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 140 (4):376-382.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Rosza, R. and K. Metzler. 1982. Plant communities of Mashomack. In: The Mashomack Preserve Study. Vol. 2: Biological Resources. S. Englebright, ed. The Nature Conservancy, East Hampton, New York.

Simko, A.L. 1987. Coastal forests of southern New England. Wildflower Notes 2: 21-26.

The President's Council on Sustainable Development. 1999. Towards a Sustainable America: Advancing Prosperity, Opportunity, and a Healthy environment for the 21st Century. Washington, DC. 97 pp. plus appendices.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Shereen Brock

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 13, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Successional maritime forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/successional-maritime-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.