Mountain Fir Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3

Vulnerable globally - At moderate risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 80 or fewer populations or locations in the world, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

Summary

Did you know?

In certain areas mountain fir forests exhibit a distinctive pattern of disturbance and regrowth called "wave-regeneration." From a distance the forest appears patchy with large areas of green canopy interspersed with crescent-shaped bands of dead trees. These fir waves consist of "troughs" of standing and windthrown dead trees, grading downhill first into a zone of vigorous fir seedlings, then into a dense stand of fir saplings, and finally to a "crest" of mature fir trees that border another band of standing dead and windthrown trees. The only other place in the world where fir waves occur is in the mountains of Japan.

State Ranking Justification

There are only 5 to 25 occurrences statewide. There are several large occurrences protected on state land. This community is restricted to the high-elevation slopes of mountainous areas generally above 4,000 feet, and includes several very large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably declining slightly due to the combined effects of atmospheric deposition, recreational overuse, and logging. This community has probably declined moderately from historical numbers likely correlated with logging and development of the surrounding landscape.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of mountain fir forests in New York has probably remained stable in recent decades as a result conservation efforts at high elevation areas in the state.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of mountain fir forests in New York has probably declined moderately from historical numbers likely correlated with past logging and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Communities that occur at higher elevations in the state (e.g., >3,000 feet) may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of atmospheric deposition and climate change, especially acid rain and temperature increase. The primary threat to mountain fir forests is acid rain deposition. The ability of forest soils to resist, or buffer, acidity depends on the thickness and composition of the soil, as well as the type of bedrock beneath the forest floor. Places in the mountainous Northeast, like New York's Adirondack and Catskill Mountains, have thin soils with low buffering capacity. Forests in high mountain regions are often exposed to greater amounts of acid than other forests because they tend to be surrounded by acidic clouds and fog that are more acidic than rainfall. When leaves are frequently bathed in this acid fog, essential nutrients in their leaves and needles are stripped away. This loss of nutrients in their foliage makes trees more susceptible to damage by other environmental factors, particularly cold winter weather (US EPA 2005). Mountain fir forests may be threatened by development, excessive logging, and recreational overuse (e.g., ATV use, hiking trails, campgounds, ski slopes).Spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) may be considered a threat to occurrences of mountain fir forest that experience extreme outbreaks, especially if it coincides with other stresses and reduces tree regeneration. The spruce budworm is a native insect that creates canopy gaps in spruce and fir forests of the eastern United States and Canada. Since 1909 there have been waves of budworm outbreaks throughout the eastern United States and Canada. The states most often affected are Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin (Kucera and Orr 1981). Balsam fir is the primary host tree for budworm in the eastern United States, although white, red, and black spruce are known to be suitable host trees. Spruce budworm may also feed on tamarack, pine, and hemlock. Spruce mixed with balsam fir is more likely to show signs of budworm infestation than spruce in pure stands (Kucera and Orr 1981).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Avoid cutting old-growth examples and encourage selective logging in areas that are under active forestry. Management activities should be consistent with recommendations presented in the High Peaks Wilderness Unit Management Plan (NYS DEC 1999).

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Survey for new occurrences in the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains in order to advance documentation and classification of mountain fir forests. A statewide review of alpine and high elevation (>3,000 feet) communities is desirable. Continue searching for large sites in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the long-term combined effects that atmospheric deposition, climate change, and extreme budworm outbreaks may have on mountain fir forest occurrences. Further research on "fir waves" may be desirable. Precise temporal and spatial mapping of fir waves may add to our understanding of this ecological process.

Rare Species

Range

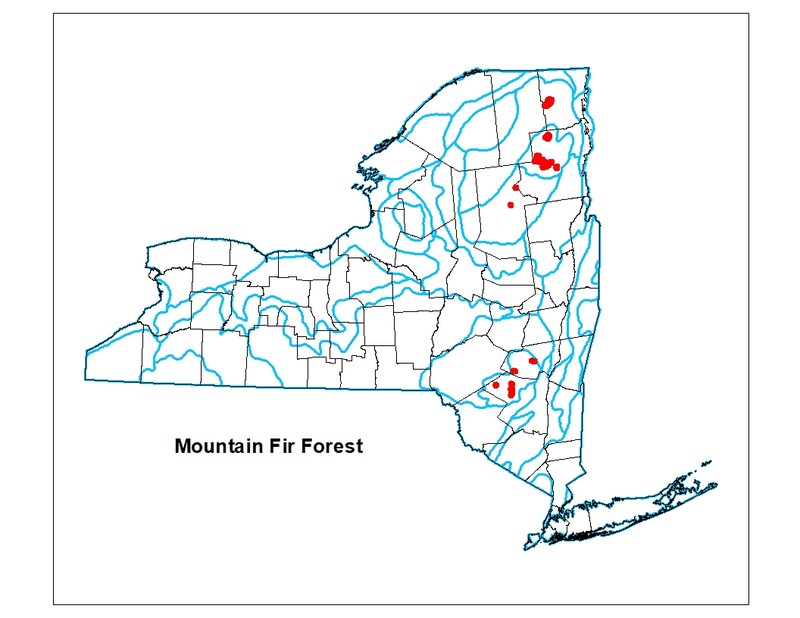

New York State Distribution

This community is known from the high-elevation slopes of mountainous areas. It is essentially restricted to the higher peaks in the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains. In the Adirondacks it is represented by large patch to matrix examples.

Global Distribution

This community is essentially restricted to high-elevation slopes of the northeastern U.S., but it is also found on the highest summits in the Catskill Peaks of New York and the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts. This range is estimated to span northwest to the Adirondack Mountains of New York, southwest to the Catskill Peaks of New York, and northeast to the peaks associated with Mount Katahdin, Maine.

Best Places to See

- Slide Mountain-Panther Mountain Wilderness Area, Catskill Park (Ulster County)

- Blackhead Range Wild Forest, Catskill Park (Greene County)

- High Peaks Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

- Dix Mountain Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

Identification Comments

General Description

Mountain fir forests have a closed canopy made up almost entirely of balsam fir (Abies balsamea), with occasional mountain paper birch (Betula cordifolia), red spruce (Picea rubens), and mountain ash (Sorbus americana). The shrub layer is dominated by balsam fir seedlings, and the ground layer has moderate herbaceous cover and a dense carpet of mosses. Along an the elevational gradient, they are often situated between mountain spruce-fir forest and alpine krummholz. This community is restricted to the high-elevation slopes of the Adirondack High Peaks and the Catskill Peaks.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This community is characteristically represented by a forest with a canopy made up almost entirely of balsam fir, located on the cool upper slopes of the Catskill and Adirondack Mountains.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 1,932 feet and 4,856 feet.

Best Time to See

Several wildflower species of mountain fir forests can be observed in bloom throughout the spring and summer. During the spring, flowers of bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis), and Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense) appear on the forest floor, followed by Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), goldthread (Coptis trifolia), and wood-sorrel (Oxalis montana). Later in the summer, flowers of mountain aster (Oclemena acuminata) and large-leaf goldenrod (Solidago macrophylla) appear.

Mountain Fir Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Balsam Fir - (Mountain Paper Birch) Forest (CEGL006112)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Acadian-Appalachian Montane Spruce-Fir Forest (CES201.566)

- Acadian-Appalachian Subalpine Woodland and Heath-Krummholz (CES201.568)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)

- Betula cordifolia (mountain paper birch)

- Picea rubens (red spruce)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Sorbus americana (American mountain-ash)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Alnus alnobetula ssp. crispa (green alder)

- Viburnum lantanoides (hobblebush)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Rubus idaeus ssp. strigosus (American red raspberry)

-

Herbs

- Clintonia borealis (blue bead-lily)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Dryopteris campyloptera (mountain wood fern)

- Dryopteris intermedia (evergreen wood fern, fancy wood fern, common wood fern)

- Erythronium americanum ssp. americanum (yellow trout-lily)

- Huperzia lucidula (shining firmoss)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Oxalis montana (northern wood sorrel)

- Solidago macrophylla (large-leaved goldenrod)

- Streptopus lanceolatus (rose twisted stalk, rose mandarin)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Dicranum fuscescens

Similar Ecological Communities

- Alpine krummholz

(guide)

Whille both comunities are dominated by balsam fir, mountain fir forests have a taller tree canopy (>5 m) compared to the stunted tree layer of alpine krummholz (<1.5 m).

- Balsam flats

(guide)

Like mountain fir forests, balsam flats have dense balsam fir cover, but they are located on moist well-drained soils of low flats adjoining swamps and gentle low ridges, rather than on cool upper slopes.

- Mountain spruce-fir forest

(guide)

Mountain spruce-fir forests are situated at lower elevations than mountain fir forests, and they feature a canopy codominated by red spruce and balsam fir, with hardwood species present in the subcanopy.

- Spruce-fir rocky summit

(guide)

Spruce-fir rocky summits have tree cover 25-60% with numerous rock outcrops. Mountain fir forests have 60% or greater tree canopy cover (>5 m).

- Spruce-northern hardwood forest

(guide)

Spruce-northern hardwood forests are situated at lower elevations than mountain fir forests, and they feature a canopy with abundant red spruce, maples (Acer spp.), beech (Fagus americana), and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis). The understory has a higher species diversity than mountain fir forests.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Mountain Fir Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Gemborys, S.R. (undated). Structure, dynamics, and pattern in a virgin northern hardwood-spruce-fir forest, The Bowl, New Hampshire. Unpublished report. Dept. biology, Hampden-Sydney College. Hampden-sydney, VA. 71 pp.

Hinrichsen, D. 1986. Waldsterben. The Amicus Journal. Spring 1986. pp. 23-27.

Kucera, D.R. and P.W. Orr. 1981. Spruce budworm in the eastern United States. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 160. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

Kudish, M. 1971. Vegetational history of the Catskill High Peaks. Dissertation Abstracts 1971, No. 71-30, 100, 270 pp.

Maloney, K.A. 1986. Wave and nonwave regeneration processes in a subalpine Abies balsamea forest. Can. J. Bot. 64:341-349.

Marchand, P.J., F.L. Goulet, and T.C. Harrington. 1986. Death by attrition: A hypothesis for wave mortality in subalpine balsam fir forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 16:591-596.

McIntosh, R.P. and R.J. Hurley. 1964. The spruce fir forests of the Catskill Mountains. Ecology 45:314-326.

Mohler, C.L., P.L. Marks, and D.G. Sprugel. 1978. Stand structure and allometry of trees during self-thinning of pure stands. J. Ecol. 66:599-614.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1999. High Peaks Wilderness Complex Unit Management Plan: Wilderness management for the High Peaks of the Adirondack Park. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY.

Nicholson, S. 1965. Altitudinal and exposure variations of the spruce-fir forest on Whiteface Mountain. M.S. Thesis, State University of New York Albany.

Rabenold, K.N. 1978. Foraging stategies, diversity, and seasonality in bird communities of Appalachian spruce-fir forests. Ecological Monographs 48(4):397-424

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Rimmer, C.C., K.P. McFarland, W.P. Ellison, and J.E. Goetz. 2001. Bicknell's Thrush (Catharus bicknelli). In The Birds of North of America, No. 592 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc, Philadelphia, PA.

Slack, Nancy G. 1977. Species diversity and community structure in bryophytes: New York State Studies. New York State Museum Bull. 428.

Sperduto, D.D. and C.V. Cogbill. 1999. Alpine and subalpine vegetation of the White Mountains, New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Sprugel, D.G. 1976. Dynamic structure of wave-regenerated Abies balsamea forests in the Northeastern United States. J. Ecol. 64: 889-911.

Sprugel, D.G. 1984. Density, biomass, productivity, and nutrient-cycling changes during stand development in wave-regenerated balsam fir forests. Ecological Monographs 54:165-186.

Sprugel, D.G. and F.H. Bormann. 1981. Natural disturbance and the steady state in high-altitude balsam fir forests. Science 211:390-393.

United States Envoronmental Protection Agency. 2005. Effects of Acid Rain: Forests. Available on line at http:www.epa.gov/airmarkets/acidrain/effects/forests.html Accessed March 2, 2005.

Vogelmann, H.W. 1985. Forest decline on Camels Hump, Vermont. Bull. Torrey Botanical Club 112(3):274-287.

Zon, R. 1914. Balsam fir. Bull. U.S. Department Agriculture No. 55:1-68.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Timothy G. Howard

Information for this guide was last updated on: March 26, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Mountain fir forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/mountain-fir-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.