Alpine Krummholz

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Barrens And Woodlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

The word krummholz is derived from German word krumm, meaning crooked, bent, or twisted; and holz for wood. High winds and frozen preciptation at high elevation causs the stunted, gnarly, and sometimes "flagged" growth forms in woody plants in this community. This community is restricted to the high-elevation slopes of mountainous areas generally above 3,500 feet.

State Ranking Justification

There are only 10 to 20 occurrences statewide. There are several occurrences protected on state land. This community is restricted to the high-elevation slopes of mountainous areas generally above 3,500 feet, and includes several high quality examples averaging slightly over 100 acres each. The current trend of this community is probably declining slightly due to the combined effects of atmospheric deposition and recreational overuse.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of alpine krummholz in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of conservation efforts at high elevation areas in the state.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of alpine krummholz in New York have probably declined slightly from historical numbers likely correlated with minor development on some summits.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Communities that occur at higher elevations in the state (e.g., >3,000 feet) may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of atmospheric deposition and climate change, especially acid rain and temperature increase. Unprotected examples of alpine krummholz may be threatened by development (e.g., communication towers and recreational overuse (e.g., hiking trails, camp sites, ski slopes, and to a lesser extent ATV use). The primary threat to alpine krummholz is acid rain deposition. The ability of forest soils to resist, or buffer, acidity depends on the thickness and composition of the soil, as well as the type of bedrock beneath the forest floor. Places in the mountainous Northeast, like New York's Adirondack and Catskill Mountains, have thin soils with low buffering capacity. Woodlands in high mountain regions are often exposed to greater amounts of acid than other woodlands because they tend to be surrounded by acidic clouds and fog that are more acidic than rainfall. When leaves are frequently bathed in this acid fog, essential nutrients in their leaves and needles are stripped away. This loss of nutrients in their foliage makes trees more susceptible to damage by other environmental factors, particularly cold winter weather (US EPA 2005).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Continue restoration efforts for severely trampled sites. Management activities should be consistent with recommendations presented in the High Peaks Wilderness Unit Management Plan (NYS DEC 1999).

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Construction of structures and trails should minimize the disturbance and subsequent erosion of the thin soils on which this community depends. Prioritize siting such development over open bedrock when possible. Trails crossing krummholz that occur in small depressions tend to collect water and become very muddy, resulting in additional trampling. Rockwork or other trail modifications that keep foot travel out of the peat is important in these cases.

Inventory Needs

Survey for new occurrences in the Adirondack Mountains in order to advance documentation and classification of alpine krummholz in order to clearly separate this community from mountain fir forests and spruce-fir rocky summits. Inventory the Catskill High Peaks to determine if this community is present. A statewide review of alpine and high elevation (>3,000 feet) communities is desirable. Need quantitative data and monitoring plots within alpine krummholz; need more work on lichens, bryophytes, and characteristic fauna. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the long-term combined effects that atmospheric deposition, climate change, and extreme budworm outbreaks may have on alpine krummholz occurrences. Compare alpine krummholz in New York with types described in NH and VT (e.g., Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Further research on "fir waves" may be desirable. Precise temporal and spatial mapping of fir waves may add to our understanding of this ecological process.

Rare Species

- Betula glandulosa (Tundra Dwarf Birch) (guide)

- Betula minor (Dwarf White Birch) (guide)

- Carex bigelowii (Bigelow's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex scirpoidea ssp. scirpoidea (Canadian Single-spike Sedge) (guide)

- Catharus bicknelli (Bicknell's Thrush) (guide)

- Diphasiastrum complanatum (Northern Ground Cedar) (guide)

- Geocaulon lividum (False Toad Flax) (guide)

- Huperzia appressa (Mountain Firmoss) (guide)

- Vaccinium boreale (Northern Lowbush Blueberry) (guide)

- Vaccinium cespitosum (Dwarf Bilberry) (guide)

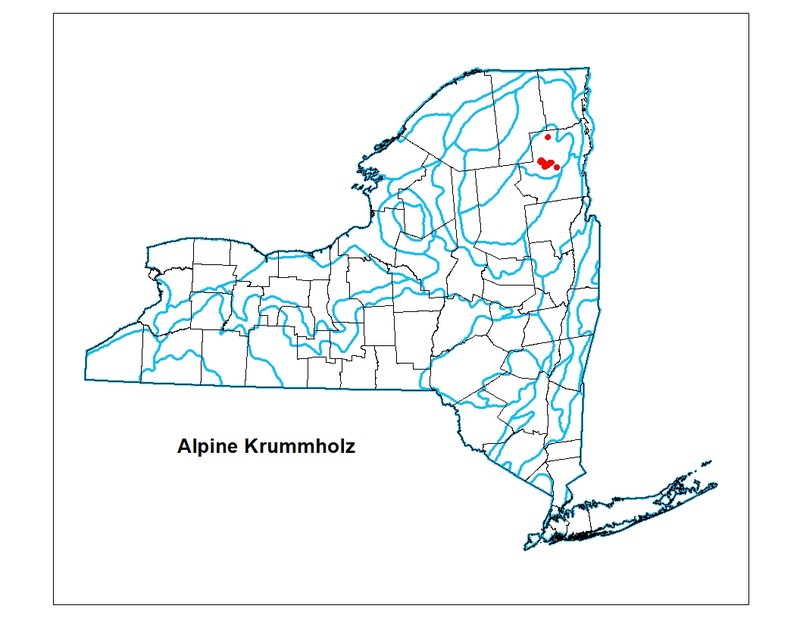

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is restricted in New York to the Adirondack High Peaks in Essex County. It is found at elevations above 3,300 feet.

Global Distribution

Essentially restricted to the high peaks of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.

Best Places to See

- High Peaks Wilderness Area

- Whiteface Mountain Ski Center

Identification Comments

General Description

Approximately 85% of the canopy consists of balsam fir; common associates include mountain paper birch (Betula cordifolia) and black spruce (Picea mariana). Less common are red spruce (Picea rubens), old-field juniper (Juniperus communis), tamarack (Larix laricina), American mountain ash (Sorbus americana), and northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis). The stunted trees form dense stands; at the uppermost elevations below timberline the trees are under 5 ft (1.5 m) tall, with branches extending to the ground (i.e., there is no self-pruning of lower branches), and an average dbh of 3 in (7.6 cm). Other low shrubs include bog bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), dwarf blueberry (Vaccinium caespitosum), velvet-leaf blueberry (Vaccinium myrtilloides), and Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum). The groundlayer is densely shaded; the groundcover consists of a thick carpet of mosses, with scattered lichens and herbs. The dominant bryophytes are Sphagnum nemoreum, Pleurozium schreberi, Dicranum scoparium, Polytrichum juniperinum, P. strictum, Ptilidium ciliare, and Paraleucobryum longifolium. Cladina rangiferina and Cetraria islandica are the most common lichens. Characteristic herbs include bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), large-leaf goldenrod (Solidago macrophylla), common wood-sorrel (Oxalis montana), goldthread (Coptis trifolia), bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis), and Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense). Characteristic birds include blackpoll warbler (Dendroica striata), white-throated sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis), dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis), yellow-rumped warbler (Dendroica coronata), and Bicknell's thrush (Catharus bicknelli).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Alpine krummholz consists of a dwarf woodland dominated by balsam fir (Abies balsamea) that occurs at or near the summits of the high peaks of the Adirondacks. The trees are generally under 2 meters (6 feet) high.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 3,379 feet and 5,282 feet.

Best Time to See

Any time in the summer when the trails are dry is an excellent time to enjoy the alpine krummholz community. Often you will find flowers under or between the dense, dwarfed trees.

Alpine Krummholz Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Black Spruce - Balsam Fir / Three-toothed Cinquefoil Shrubland (CEGL006038)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Acadian-Appalachian Subalpine Woodland and Heath-Krummholz (CES201.568)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Betula cordifolia (mountain paper birch)

- Larix laricina (tamarack)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

- Picea rubens (red spruce)

- Rhododendron groenlandicum (Labrador-tea)

- Sorbus americana (American mountain-ash)

- Vaccinium cespitosum (dwarf bilberry)

- Vaccinium myrtilloides (velvet-leaved blueberry)

- Vaccinium uliginosum (bog bilberry)

-

Herbs

- Clintonia borealis (blue bead-lily)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Oxalis montana (northern wood sorrel)

- Solidago macrophylla (large-leaved goldenrod)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Mountain fir forest

(guide)

Whille both comunities are dominated by balsam fir, mountain fir forests have a taller tree canopy (>5 m) compared to the stunted tree layer of alpine krummholz (<1.5 m).

- Mountain spruce-fir forest

(guide)

Mountain spruce-fir forests have a taller canopy (>5 m) co-dominated by red spruce and balsam fir. Alpine krummholz is dominated (50-85%) by stunted (<1.5 m) balsam fir.

- Open alpine community

(guide)

The open alpine community consists of a mosaic of sedge/dwarf shrub meadows, dwarf heath shrublands, small boggy depressions, and exposed bedrock covered with lichens and mosses. Stunted tree cover <25%. Alpine krummholz is dominated (50-85%) by stunted (<1.5 m) balsam fir.

- Spruce-fir rocky summit

(guide)

Spruce-fir rocky summits have patchy vegetation dominated by red spruce and balsam fir with numerous rock outcrops. Alpine krummholz is dominated (50-85%) by stunted (<1.5 m) balsam fir often forming a dense thicket.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Alpine Krummholz. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

DiNunzio, M.G. 1972. A vegetational survey of the alpine zone of the Adirondack Mountains, New York. M.S. Thesis. SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

LeBlanc, D.C. 1981. Ecological studies on the alpine vegetation of the Adirondack Mountains of New York. M.A. Thesis. SUNY - Plattsburg. Plattsburg, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Slack, Nancy G. and A.W. Bell. 1993. 85 acres: a field guide to the Adirondack alpine summits. Adirondack Mountain Club, Lake George, NY.

Slack, Nancy G. and A.W. Bell. 1995. Field guide to the New England alpine summits. Appalachian Mountain Club, Boston, MA.

Sperduto, D.D. and C.V. Cogbill. 1999. Alpine and subalpine vegetation of the White Mountains, New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

United States Envoronmental Protection Agency. 2005. Effects of Acid Rain: Forests. Available on line at http:www.epa.gov/airmarkets/acidrain/effects/forests.html Accessed March 2, 2005.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 14, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Alpine krummholz.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/alpine-krummholz/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.