Freshwater Tidal Swamp

- System

- Estuarine

- Subsystem

- Estuarine Intertidal

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G2

Imperiled globally - At high risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in the world, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

Summary

Did you know?

Did you know you can canoe through one of the largest tidal swamps in the state? Accessible from Ramshorn Creek, you can canoe to Ramshorn-Livingston Sanctuary, a preserve that includes a 400-acre tidal swamp. The sanctuary is owned and managed the National Audubon Society and Scenic Hudson. Educational programs, including field trips for school groups and birding trips are offered. Bald eagles, waterfowl, woodcocks, and other birds and wildlife have been spotted on the property. To visit the preserve, go to http://ny.audubon.org/ramshorn.htm

State Ranking Justification

An uncommon natural community occurring in a very restricted area in the state. Additionally, this community occurs at the juncture between the Hudson River and land, an area that is commonly developed. Many sites were likely lost historically as a result.

Short-term Trends

While most of the original tidal swamps were lost through historical shoreline development, the swamps remaining are likely stable and total acreage is probably no longer decreasing.

Long-term Trends

The number of freshwater tidal marshes in New York probably declined moderately from historical numbers as a result of shoreline development (e.g., railroads) and river channel dredging.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The main direct threats to this community are construction or filling, in or near the swamps, especially if the activity alters the natural tidal regime. Even in protected lands, road building and other activities may threaten this community in these ways. River pollution is a threat to the organisms in this community and in the adjacent wetlands. Invasive species, such as yellow iris (Iris pseudacorus), are a threat to a few examples.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

This community requires natural tidal flooding; any activity in the vicinity of freshwater tidal swamp must ensure the maintainence of tidal flooding. Also, consider removing any existing blockages to flooding and existing channels that might accelerate drainage.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Buffers that diminish or eliminate disturbances in this estuarine community are critical considerations for any development project. Such disturbances include the influx of water-borne solutes (road salt, fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, sewage), water-borne sediments, and noise pollution. Additionally, hydrologic connectivity to the river must be maintained so that unimpeded tidal flow can reach the swamp. When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Additional sites might still be found along the Hudson River, although it is likely they will be small and disturbed.

Research Needs

Research is needed to clearly separate this community from floodplain forest on the ground. It is possible that a few present-day floodplain forests along the Hudson River were formerly freshwater tidal swamps prior to dredge spoil deposition or other hydrological alterations.

Rare Species

Range

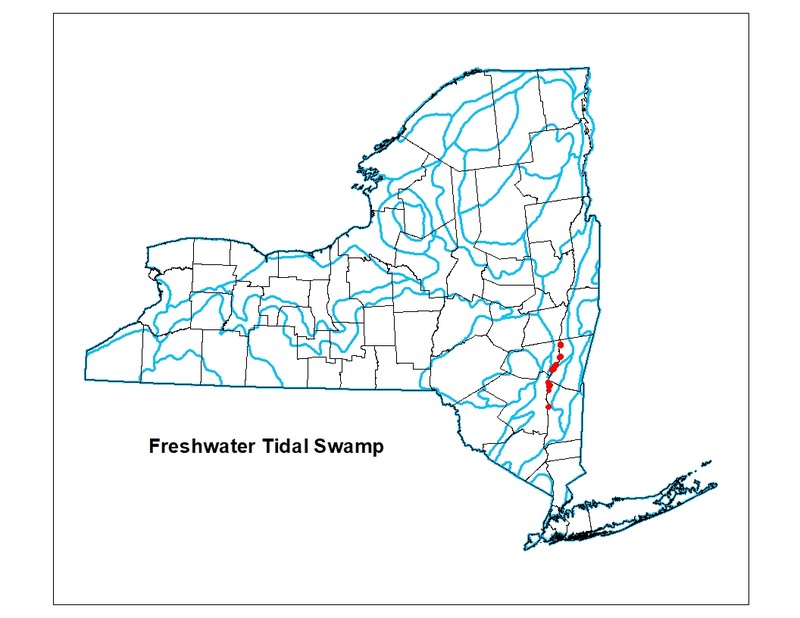

New York State Distribution

This community is currently restricted to the central Hudson Valley portion of the Hudson River within Columbia, Dutchess, Greene, and Ulster Counties.

Global Distribution

This freshwater tidal swamp community is restricted to the freshwater tidal portions of rivers in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey.

Best Places to See

- RamsHorn-Livingston Sanctuary (Greene County)

- Tivoli Bays Wildlife Management Area

- Lewis A. Swyer Preserve

Identification Comments

General Description

A forested or shrub-dominated tidal wetland that occurs in lowlands along large river systems characterized by gentle slope gradients coupled with tidal influence over considerable distances. The swamp substrate is always wet and is subject to regular flooding by fresh tidal water. The water salinity values are less than 0.5 parts per thousand (ppt).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This community has a relatively high abundance of woody plants in contrast to the non-woody plants found in tidal marshes, and is influenced by the daily rise and fall of a freshwater tidal river or bay.

Best Time to See

Different viewing opportunities present themselves throughout the growing season. In early spring, skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) flowers may be visible pushing through the snow, and soon after spice bush (Lindera benzoin) blooms with tiny yellow flowers. In late summer (late August through September), herbaceous plants are at their largest and are a treat to see.

Freshwater Tidal Swamp Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Red Maple - Green Ash / Knotweed species Tidal Woodland (CEGL006165)

- (Speckled Alder, Hazel Alder) - Silky Dogwood Tidal Shrub Swamp (CEGL006337)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Tidal Swamp (CES203.282)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Carpinus caroliniana ssp. virginiana (musclewood, ironwood, American hornbeam)

- Fraxinus nigra (black ash)

- Fraxinus pennsylvanica (green ash)

- Ulmus rubra (slippery elm)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Alnus incana ssp. rugosa (speckled alder)

- Alnus serrulata (smooth alder)

- Cornus amomum ssp. amomum (silky dogwood)

- Cornus racemosa (gray dogwood, red-panicled dogwood)

- Cornus sericea (red-osier dogwood)

- Lindera benzoin (spicebush)

- Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum (smooth arrowwood)

-

Vines

- Apios americana (groundnut)

- Dioscorea villosa (wild yam)

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Ageratina altissima var. altissima (common white snakeroot)

- Amphicarpaea bracteata (hog peanut)

- Arisaema triphyllum ssp. triphyllum (common jack-in-the-pulpit)

- Asclepias incarnata ssp. incarnata (western swamp milkweed)

- Bidens discoidea (few-bracted beggar-ticks)

- Bidens laevis (smooth beggar-ticks)

- Boehmeria cylindrica (false nettle)

- Carex grayi (Gray's sedge)

- Cicuta maculata var. maculata (spotted water-hemlock)

- Cinna arundinacea (stout wood-reed)

- Impatiens capensis (spotted jewelweed, spotted touch-me-not)

- Iris pseudacorus (yellow iris)

- Laportea canadensis (wood-nettle)

- Leersia oryzoides (rice cut grass)

- Lobelia cardinalis (cardinal flower)

- Lysimachia nummularia (moneywort, creeping-Jenny)

- Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife)

- Mimulus ringens (Allegheny monkey-flower)

- Onoclea sensibilis (sensitive fern)

- Peltandra virginica (green arrow-arum, tuckahoe)

- Persicaria arifolia (halberd-leaved tear-thumb)

- Persicaria hydropiper (water-pepper)

- Persicaria hydropiperoides (mild water-pepper)

- Persicaria sagittata (arrow-leaved tear-thumb)

- Pilea fontana (black-fruited clearweed)

- Pilea pumila var. pumila (green-fruited clearweed)

- Ranunculus hispidus (woodland butter-cup, woodland crow-foot)

- Rumex verticillatus (swamp dock)

- Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (calico-aster)

- Symplocarpus foetidus (skunk-cabbage)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Floodplain forest

(guide)

Floodplain forests may occur nearby or even adjacent to freshwater tidal swamps, however foodplain forests will occur on slightly higher terrain and tend to be flooded less regularly.

- Freshwater tidal marsh

(guide)

Freshwater tidal swamps are dominated by trees and shrubs, whereas freshwater tidal marshes are dominated by herbaceous species.

- Red maple-hardwood swamp

(guide)

Similar species may be present in a red maple-hardwood swamp but the freshwater tidal swamp has the tidal influence that a red maple-hardwood swamp does not have.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Freshwater Tidal Swamp. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Breden, T.F. 1988. A tidal swamp forest in New Jersey. Bartonia 54: 146.

DeVries, C. and C.B. DeWitt. 1986. Freshwater tidal wetlands community description and relation of plant distribution to elevation and substrate. In: Polgar Fellowship Reports of the Hudson River National Estuarine Sanctuary Program 1986. E.A. Blair and J.C. Cooper, editors. Hudson River Foundation, New York, New York.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Findlay, S.E.G., E. Kiviat, W.C. Nieder, and E.A. Blair. 2002. Functional assessment of a reference wetland set as a tool for science, management and restoration. Aquat. Sci. 64:107-117.

Kiviat, E. 1974. A fresh-water tidal marsh on the Hudson, Tivoli North Bay. Paper 14, In Third Symposium on Hudson River Ecology, Hudson River Environmental Society, Bronx, New York.

Kiviat, E. 1979. Hudson River Estuary shore zone: ecology and management. MA Thesis, State University College, New Paltz, New York.

Kiviat, E. 1983. Fresh-tidal swamp vegetation, Hudson River. Estuaries 6(3):279.

Kiviat, Erik and Gretchen Stevens. 2001. Biodiversity assessment manual for the Hudson River Estuary Corridor. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY.

Leonardi, L. 1991. Bryophytes of two New York State freshwater tidal swamps. Evansia 8(1):22-25.

Leonardi, L. and E. Kiviat. 1990. The bryophytes of the Tivoli Bays freshwater tidal swamps. Section III: 23 pp. In J.R. Waldman and E.A. Blair (eds.). Polgar Fellowship Reports of the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve Program, 1989. Hudson River Foundation, New York.

McVaugh, R. 1958. Flora of the Columbia County area, New York. Bull. 360. New York State Museum and Science Service. University of the State of New York. Albany, NY. 400 pp.

Muenscher, W.C. 1937. VII. Aquatic vegetation of the Lower Hudson area. 1936. Biological Survey. 11:231-248.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Noss, R.F., E.T.I. LaRoe, and J.M. Scott. 2001. Endangered Ecosystems of the United States: A Preliminary Assessment of Loss and Degradation. United States Geological Survey, Biological Resources. 74 pp. Available at http://biology.usgs.gov/pubs/ecosys.htm.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Rheinhardt, R. 1992. A multivariate analysis of vegetation patterns in tidal freshwater swamps of lower Chesapeake Bay, USA. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119:192-207.

Westad, Kristen E. 1987. Addendum to flora of freshwater tidal swamps at Tivoli Bays. Section X: 1 p. In E.A. Blair (eds.), Final Reports of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Reports of the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve Program, 1986. Hudson River Foundation, New York.

Westad, Kristen E. and E. Kiviat. 1986. Flora of freshwater tidal swamps at Tivoli Bays, Hudson River National Estuarine Sanctuary. Unpublished report of Bard College Ecology Field Station.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Timothy G. Howard

Information for this guide was last updated on: January 18, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Freshwater tidal swamp.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/freshwater-tidal-swamp/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.