Maritime Bluff

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

The planners of the Montauk Point Lighthouse were well aware of erosion. The government agents noted that "Montauk Point is washed by the sea in storms" and "wastes very fast." They erected the lighthouse at the extreme west end of the Turtle Hill plateau at a distance of approximately 300 feet from the bluff. Over the past 200 years approximately 200 feet of Montauk Point has been washed into the Atlantic Ocean. Today the lighthouse stands less than 100 feet from the edge of the maritime bluff.

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 5 to 30 extant occurrences statewide. One currently documented occurrence has good viability and is located on public conservation land. The community is currently known from the Coastal Lowlands ecozone of eastern Long Island in Suffolk County. The overall trend for the community is suspected to be slightly declining due to recreational overuse and coastal development.

Short-term Trends

Although the number of maritime bluffs may have increased slightly when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development, their acreage in New York has probably declined in recent decades as a result of coastal development and recreational overuse.

Long-term Trends

Although the number of maritime bluffs in New York may have increased slightly from historical numbers when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development into numerous large and small stretches, their aerial extent and viability are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in connectivity, tidal hydrology, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The primary threat to maritime bluffs in New York is likely to be recreational overuse; specifically, climbing and sliding on the cliffs increases erosion. Invasive exotic species that appear on the bluffs include rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa) and Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus scandens). In some cases, exotics are being planted to stabilize the bluff. Additional threats include fragmentation of bluffs by development; stairways for beach access; and barriers to connectivity between the open ocean, the beach, and the bluffs. Broad threats to maritime beach dynamics also threaten maritime bluffs. Hydrologic alterations to tidal dynamics, shoreline fragmentation and hardening, altered sediment budgets, and management practices like beach replenishment affect the natural cycles of sand deposition and attrition and subsequently change the rate of erosion of the bluffs.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Maintain the dominant ecological processes responsible for keeping this dynamic community in disclimax. Natural disturbances, including wave erosion and strong offshore winds, should be expected to lead to slumping, cliff retreat, and sea cave formation. Prevent recreational overuse and encourage the public to stay on marked trails. In particular, continue to restrict sliding and climbing on the face of the bluffs using signage and fencing. In places where trails run directly along the top edge of maritime bluffs, those trails should be re-routed away from the edge and split rail fences could be used to direct visitors to designated overlooks. Because the face of the bluffs can be expected to migrate inland, it is important to protect adequate open space to accommodate such change. Avoid planting invasive exotic species to stabilize the bluffs; if stabilization of this inherently unstable community is necessary, select native plants, perhaps American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata). Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the bluffs through appropriate direct management and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as beach access trails and stairways.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

This community is best protected as part of a large maritime system, encompassing grasslands, shrublands, bluffs, heathland, forests, barrens, and dunes. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow for nutrient flow, seed dispersal, and seasonal animal migrations within them. Bisecting trails, roads, and developments can also allow exotic plant and animal species to invade and potentially increase 'edge species' (such as raccoons, skunks, and foxes). Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities and to shallow offshore communities should also be maintained as much as possible to maintain "maritime" conditions, which imply deposition of salt spray and shearing from offshore winds.

Inventory Needs

Surveys and documentation of additional occurrences are needed, as are data on rare and characteristic animals.

Research Needs

A study could investigate the effects of sea level rise and changes in oceanic dynamics with global climate change on the dynamic erosive processes of this community.

Rare Species

Range

New York State Distribution

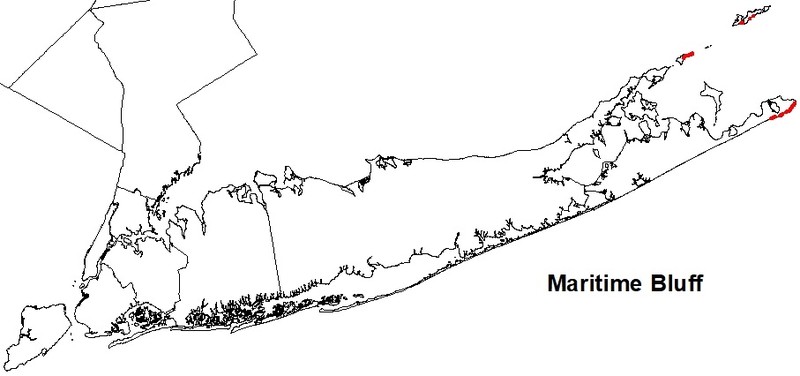

This community is currently known from the Coastal Lowlands ecozone of eastern Long Island in Suffolk County. It primarily occurs on the eastern end of Long Island, along the south shore, but also appears in discontinuous patches along the north shore and east to Plum Island and Fishers Island. It may extend west into Nassau County.

Global Distribution

Maritme bluffs occur along the North Atlantic Coast from Long Island, New York to Maine.

Best Places to See

- Montauk Point State Park (Suffolk County)

- Shadmore State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A sparsely vegetated community that occurs on vertical exposures of unconsolidated material, such as small stone, gravel, sand, and clay, that is exposed to maritime forces, such as water, ice, or wind. There are very few woody species present because of the unstable substrate. The most abundant species are usually annual and early successional herbs. These bluffs are adjacent to maritime and marine communities and are actively eroded by oceanic forces.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The maritime bluff is comprised of areas of unvegetated, near vertical morainal sand cliffs, and less steep (about 45 degrees) areas of slumped bluff-face at the base of the bluff that support American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), seaside goldenrod (Soligago sempervirens), and bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 3 feet and 77 feet.

Best Time to See

These dramatic bluffs are scenic year round. Visit during the summer and enjoy the beach below.

Maritime Bluff Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- North Atlantic Maritime Erosional Bluff Sparse Vegetation (CEGL006618)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northeastern Erosional Bluff (CES203.498)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Baccharis halimifolia (groundsel-tree)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Rhus copallinum var. copallinum (common winged sumac)

- Rhus glabra (smooth sumac)

- Rubus allegheniensis (common blackberry)

- Rubus flagellaris (northern dewberry)

-

Tree saplings

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Tree seedlings

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Vines

- Calystegia sepium (hedge bindweed)

- Celastrus orbiculatus (Oriental bittersweet)

- Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle)

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

-

Herbs

- Achillea millefolium (yarrow)

- Ammophila breviligulata (beach grass)

- Cakile edentula var. edentula (American sea rocket)

- Cyperus grayi (Gray's flat sedge)

- Dichanthelium columbianum (District of Columbia rosette grass)

- Lathyrus japonicus var. maritimus (beach-pea)

- Oenothera biennis (common evening-primrose)

- Phragmites australis (old world reed grass, old world phragmites)

- Phytolacca americana var. americana (pokeweed)

- Raphanus raphanistrum ssp. raphanistrum (wild radish)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

- Xanthium strumarium var. strumarium (European cocklebur)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Calcareous cliff community

(guide)

Calcareous cliff communities occur on vertical exposures of calcareous bedrock types, such as dolomite or limestone rather than on unconsolidated morainal sand cliffs adjacent to the ocean.

- Cliff community

(guide)

Cliff communities occur on bedrock outcrops that are usually inland from the ocean rather than on unconsolidated morainal sand cliffs adjacent to the ocean.

- Great Lakes bluff

(guide)

Great Lakes bluffs also occur on vertical exposures of unconsolidated material but they are adjacent to one of the Great Lakes rather than adjacent to the ocean.

- Maritime dunes

(guide)

Maritime dunes form on active and stabilized sand dunes that have a low, rolling form. They are often vegetated, either with a near monoculture of American beachgrass or with a mix of grasses and forbs. Maritime bluffs, on the other hand, are nearly vertical morainal cliffs made up of semiconsolidated sand, stone, gravel, and clay. They are only sparsely vegetated.

- Shale cliff and talus community

(guide)

Shale cliff and talus community occurs inland on nearly vertical exposures of shale bedrock and includes ledges and small areas of talus rather than on unconsolidated morainal sand cliffs adjacent to the ocean.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Bluff. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Larson, D.W., U. Matthes, and P.E. Kelly. 2000. Cliff Ecology: Pattern and Process in Cliff Ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, New York, New York.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Schlesinger, M.D., E.L. White, S.M. Young, G.J. Edinger, K.A. Perkins, N. Schoppmann, and D. Parry. 2016. Biodiversity Inventory of Plum Island, New York. New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany, New York, and SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

Van Diver, Bradford B. 1985. Roadside Geology of New York. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, MT.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime bluff.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-bluff/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.