Cliff Community

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S4

Apparently Secure in New York - Uncommon in New York but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of the state; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G5

Secure globally - Common in the world; widespread and abundant (but may be rare in some parts of its range).

Summary

Did you know?

Cliff communities can harbor some of the oldest trees in the state. Because of the inaccessible nature of cliffs, the vegetation at these sites is often left undisturbed. In addition, the trees that reside on cliffs grow under stressful conditions, including drought, high wind, and low nutrient availability, often making them stunted, knobby, and undesirable for commercial lumber. The small size of these trees can be deceiving. Studies of the Niagara Escarpment, which extends from New York into Ontario, Canada, have found northern white cedar trees (Thuja occidentalis) that are 500 to 1000 years old.

State Ranking Justification

There are several thousand occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and many are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is limited to areas of the state with acidic bedrock outcrops that are sufficiently high and steep. Although most examples are relatively small, there are several large, high quality examples in New York. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include mineral extraction, recreational overuse, and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of cliff communities in New York have probably declined slightly in recent decades as a result of mineral extraction and other development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of cliff communities in New York have probably declined moderately from historical numbers as a result of mineral extraction and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Cliff communities are threatened by adjacent upslope development (e.g., residential, agricultural, industrial) and its associated run-off. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., mining, excessive logging adjacent forests). Recreational overuse in the form of concentrated or sustained rock climbing is a particular threat to this community. Relatively minor recreational overuse adjacent to cliffs is a lesser threat (e.g., ATVs, trampling by visitors, campgrounds, picnic areas, trash dumping). Several cliff communities are threatened by invasive species, such as tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima). These threats also have an impact on rare cliff-dwelling plants and animals, such as mountain spleenwort (Asplenium montanum) and peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical establish and maintain a natural forested buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the cliff face. Avoid habitat alteration along the cliff and surrounding landscape. Restore past impacts (e.g., mining). Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species onto the cliff through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as trails and utility ROWs. Monitor rock climbing activity and develop a management plan for sites where recreational overuse is a concern.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

A natural (usually forested) buffer around the cliff face will help it maintain the characteristics that make it unique. It may be desirable to close portions of cliffs for various durations in order to protect rare cliff nesting birds and rare plant habitat.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of cliff communities. A statewide review of cliff communities is desirable, perhaps using GIS modeling to locate new occurrences. Continue searching for large cliffs in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the age of the trees growing on cliffs. Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct cliff types based on composition (e.g., bryophytes) and physical characteristics. The current classification encompasses a wide range of bedrock from pure acidic (e.g., granite, gneiss) to circumneutral bedrock (e.g., amphibolite, schist). Entire cliffs or portions of cliffs can be further classified along a moisture gradient (e.g., dry, moist, wet). These types may correspond to ecoregional distribution, specific geology, and/or local hydrology.

Rare Species

- Anthoxanthum monticola ssp. monticola (Alpine Sweetgrass) (guide)

- Aquila chrysaetos (Golden Eagle) (guide)

- Asplenium bradleyi (Bradley's Spleenwort) (guide)

- Asplenium montanum (Mountain Spleenwort) (guide)

- Carex houghtoniana (Houghton's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex merritt-fernaldii (Fernald's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex nigromarginata (Black-edged Sedge) (guide)

- Corydalis aurea (Golden Corydalis) (guide)

- Crotalus horridus (Timber Rattlesnake) (guide)

- Draba arabisans (Rock Whitlow Grass) (guide)

- Dryopteris fragrans (Fragrant Cliff Fern) (guide)

- Epilobium hornemannii ssp. hornemannii (Alpine Willowherb) (guide)

- Fabronia ciliaris (Fringed Fabronia) (guide)

- Falco peregrinus (Peregrine Falcon) (guide)

- Festuca saximontana var. saximontana (Mountain Fescue) (guide)

- Huperzia appressa (Mountain Firmoss) (guide)

- Hydrangea arborescens (Wild Hydrangea) (guide)

- Myotis leibii (Eastern Small-footed Myotis) (guide)

- Myriopteris lanosa (Woolly Lip Fern) (guide)

- Nabalus boottii (Boott's Rattlesnake Root) (guide)

- Oreojuncus trifidus (Highland Rush) (guide)

- Pellaea glabella ssp. glabella (Smooth Cliffbrake) (guide)

- Philonotis capillaris (Hairy Apple Moss) (guide)

- Pinguicula vulgaris (Butterwort) (guide)

- Primula mistassinica (Bird's Eye Primrose) (guide)

- Rhodiola integrifolia ssp. leedyi (Leedy's Roseroot) (guide)

- Rhodiola rosea (Common Roseroot) (guide)

- Saxifraga aizoides (Yellow Mountain Saxifrage) (guide)

- Saxifraga paniculata ssp. paniculata (White Mountain Saxifrage) (guide)

- Schwetschkeopsis fabronia (False Hair Moss) (guide)

- Silene caroliniana ssp. pensylvanica (Wild Pink) (guide)

- Solidago leiocarpa (Alpine Goldenrod) (guide)

- Solidago racemosa (Riverbank Goldenrod) (guide)

- Solidago randii (Rand's Goldenrod) (guide)

- Woodsia alpina (Alpine Cliff Fern) (guide)

Range

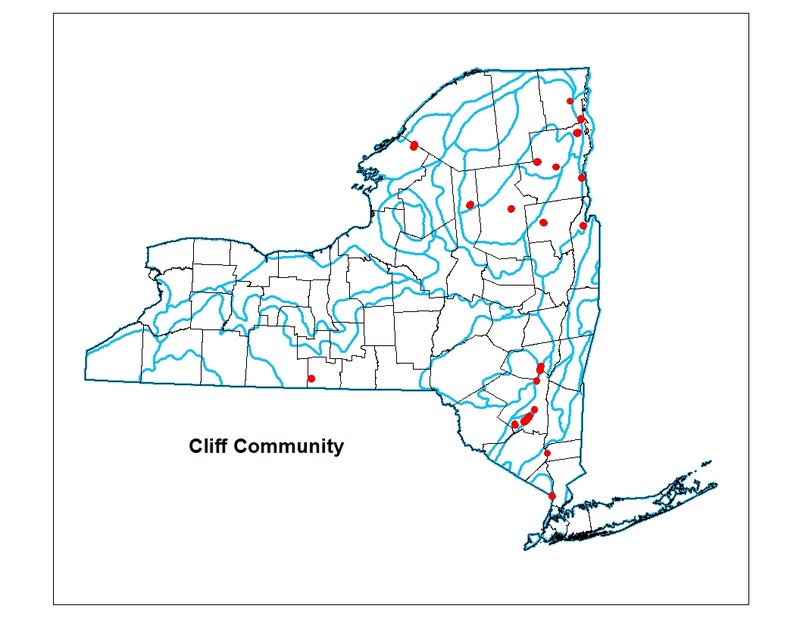

New York State Distribution

Cliff communities are widespread throughout upstate New York, north of the North Atlantic Coast Ecoregion, where the bedrock is non-calcareous. This community is currently known from the Central High Allegheny Plateau, the Catskill Mountains, and the Hudson Highlands. Numerous cliffs are also known from the Central Adirondack Mountains and Eastern Adirondack Low Mountains (Lake George Valley). Additional occurrences may be located elsewhere in the state where similar environmental conditions exist.

Global Distribution

This physically broadly-defined community may be worldwide, where the bedrock is not calcareous. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are suspected to span north to southern Canada, west to Minnesota, south to Indiana and Tennessee, southeast to Georgia and northeast to Nova Scotia.

Best Places to See

- Dix Mountain Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park

- Virgina V. Smiley Preserve (Ulster County)

- Catskill Park (Greene County)

- West Canada Lakes Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park (Hamilton County)

Identification Comments

General Description

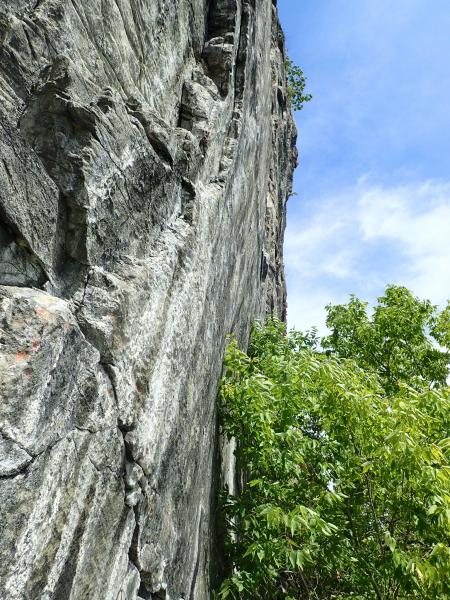

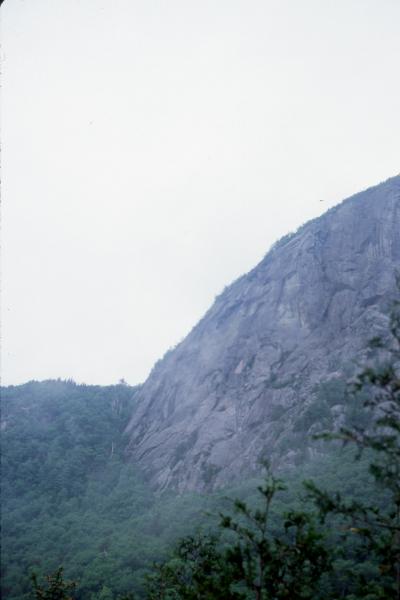

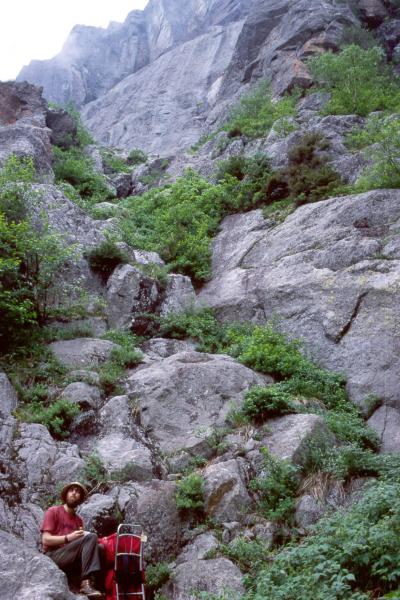

A community that occurs on vertical exposures of resistant, non-calcareous bedrock (such as quartzite, sandstone, or schist) or consolidated material; these cliffs often include ledges and small areas of talus. There is minimal soil development, and vegetation is usually sparse. Plant species present are somewhat dependent on the microclimate conditions, which can range from shady and moist to sun-exposed and dry. Vegetation often inhabits shallow pockets of soil that accumulate on ledges, and in cracks and crevices within the cliff wall.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic species include rock polypody (Polypodium virginianum), marginal wood fern (Dryopteris marginalis), common hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa), mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). Bryophytes that are characteristic of acidic cliffs include the mosses Andreaea rothii, Dicranum fulvum, Dicranum montanum, white cushion moss (Leucobryum glaucum), Plagiothecium laetum, Pohlia nutans, Pylaisiadelpha tenuirostris, and the leafy liverworts Blepharostoma trichophyllum, Jamesoniella autumnalis, and Scapania nemorea. The rare two-ranked moss (Pseudotaxiphyllum distichaceum) and the uncommon leafy liverwort Herbertus aduncus ssp. tenuis are also known from acidic cliff communities. The common raven (Corvus corax) is a characteristic bird that nests on cliffs.

Best Time to See

Impressively large cliffs can be viewed from afar year-round. Many natural areas across the state have cliffs that provide excellent scenic vantage points from which to observe the landscape from above. Late spring to early summer is the best time to see early blooming cliff-dwelling wildflowers.

Cliff Community Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Eastern Red-cedar / Rock Harlequin Cliff Sparse Vegetation (CEGL006422)

- (Rock Polypody, Appalachian Polypody) Cliff Sparse Vegetation (CEGL006528)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)

- Betula lenta (black birch)

- Betula papyrifera (paper birch)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer pensylvanicum (striped maple)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Diervilla lonicera (bush-honeysuckle)

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Kalmia angustifolia var. angustifolia (sheep laurel, sheep-kill)

- Rubus odoratus (purple-flowering raspberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

-

Vines

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

-

Herbs

- Aquilegia canadensis (wild columbine, red columbine)

- Asplenium trichomanes ssp. trichomanes (maidenhair spleenwort)

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Campanula rotundifolia (hare-bell)

- Dryopteris marginalis (marginal wood fern)

- Eurybia divaricata (white wood-aster)

- Polypodium virginianum (Virginian rock polypody, Virginian polypody)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Andreaea rothii

- Anomodon attenuatus

- Anomodon rostratus

- Dicranum fulvum

- Pohlia nutans

- Pseudotaxiphyllum elegans

- Scapania nemorea

- Umbilicaria spp.

Similar Ecological Communities

- Calcareous cliff community

(guide)

Calcareous cliff communities have shallow soils and sparse vegetation, but they occur on vertical exposures of calcareous bedrock types, such as dolomite or limestone.

- Great Lakes bluff

(guide)

Great Lakes bluffs occur on unconsolidated substrate adjacent to one of the Great Lakes, rather than on bedrock outcrops.

- Maritime bluff

(guide)

Maritime bluffs occur on unconsolidated substrate adjacent to the ocean, rather than on bedrock outcrops that are usually inland from the ocean.

- Shale cliff and talus community

(guide)

Shale cliff and talus communities occur on vertical, and nearly vertical exposures of shale bedrock, and include areas of talus.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Cliff Community. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Larson, D.W., U. Matthes, and P.E. Kelly. 2000. Cliff Ecology: Pattern and Process in Cliff Ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, New York, New York.

Lougee, J. 2000. Sam's Point Dwarf Pine Ridge Preserve Cliff community survey. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern New York Chapter, Troy, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Thompson, J.E. 1999. Cliff and talus survey of the Mohonk Preserve. Unpublished report. Daniel Smiley Research Center, New Paltz, NY

Van Diver, Bradford B. 1985. Roadside Geology of New York. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, MT.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 13, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Cliff community.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/cliff-community/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.