Calcareous Cliff Community

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Cliff communities can harbor some of the oldest trees in the state. Because of their inaccessibility, the vegetation at these sites is often left undisturbed. In addition, the trees that reside on cliffs grow under stressful conditions, including drought, high wind, and low nutrient availability, often making them stunted, knobby, and undesirable for commercial lumber. The small size of these trees can be deceiving. Studies of the Niagara Escarpment, which extends from New York into Ontario, Canada, have found northern white cedar trees (Thuja occidentalis) that are 500 to 1000 years old!

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and many are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is limited to the calcareous regions of the state, and there are several large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include mineral extraction, recreational overuse, and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of calcareous cliffs in New York have probably declined slightly in recent decades as a result of mineral extraction and other development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of calcareous cliffs in New York have probably declined moderately from historical numbers as a result of mineral extraction and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Calcareous cliff communities are threatened by adjacent upslope development (e.g., residential, agricultural, utility ROWs, roads) and its associated run-off. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., mining, excessive logging of adjacent forests). Recreational overuse in the form of concentrated or sustained rock climbing is a particular threat to this community. Relatively minor recreational overuse adjacent to cliffs is a lesser threat (e.g., ATVs, trampling by visitors, campgrounds, picnic areas, trash dumping). Several cliff communities are threatened by invasive species, such as black swallow-wort (Cynanchum spp.), Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa), garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), and tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural forested buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the cliff face. Avoid habitat alteration along the cliff and surrounding landscape. Restore sites that have been unnaturally disturbed (e.g., from mining). Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species onto the cliff through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as trails and utility ROWs. Monitor rock climbing activity and develop a management plan for sites where recreational overuse is a concern.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

A natural (usually forested) buffer around the cliff face will help to maintain the characteristics that make it unique. It may be desirable to close portions of cliffs for various durations in order to protect rare cliff nesting birds and rare plant habitat.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of calcareous cliffs. A statewide review of calacareous cliffs is desirable, perhaps using GIS modeling to locate new occurrences. Continue searching for large cliffs in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the age of the trees growing on limestone cliffs. Several-hundred-year-old northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis) trees have been reported on similar cliffs in Ontario, Canada (Kelly and Larson 1997). Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct calcareous cliff types based on species composition (e.g., bryophytes) and physical characteristics. The current classification encompasses a wide range of calcareous bedrock (e.g., limestone, dolostone, calcite, or marble), including circumneutral bedrock (e.g., amphibolite), calcareous shales, and even acidic bedrock with large calcareous intrusions. Entire cliffs or portions of cliffs can be further classified along a moisture gradient (e.g., dry, moist, wet). These types may correspond to ecoregional distribution, specific limestone geology, and/or local hydrology.

Rare Species

- Aconitum noveboracense (Northern Monkshood) (guide)

- Allium cernuum var. cernuum (Nodding Wild Onion) (guide)

- Anticlea elegans var. glauca (White Death Camas) (guide)

- Asplenium scolopendrium var. americanum (Hart's-tongue Fern) (guide)

- Asplenium viride (Green Spleenwort) (guide)

- Asterocampa clyton (Tawny Emperor) (guide)

- Astragalus neglectus (Cooper's Milkvetch) (guide)

- Blephilia ciliata (Downy Wood Mint) (guide)

- Boechera grahamii (Graham's Rock Cress) (guide)

- Boechera stricta (Drummond's Rock Cress) (guide)

- Borodinia missouriensis (Green Rock Cress) (guide)

- Bouteloua curtipendula var. curtipendula (Side Oats Grama) (guide)

- Carex backii (Back's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex capillaris (Hair-like Sedge) (guide)

- Carex formosa (Handsome Sedge) (guide)

- Carex garberi (Elk Sedge) (guide)

- Carex scirpoidea ssp. scirpoidea (Canadian Single-spike Sedge) (guide)

- Cirriphyllum piliferum (Hair-pointed Moss) (guide)

- Conardia compacta (Coast creeping moss) (guide)

- Corydalis aurea (Golden Corydalis) (guide)

- Coscinodon cribrosus (Sieve-toothed dry rock moss) (guide)

- Crotalus horridus (Timber Rattlesnake) (guide)

- Cypripedium arietinum (Ram's Head Lady's Slipper) (guide)

- Didymodon ferrugineus (Rusty Beard-moss) (guide)

- Draba arabisans (Rock Whitlow Grass) (guide)

- Draba glabella (Smooth Whitlow Grass) (guide)

- Erigeron hyssopifolius (Hyssop-leaved Fleabane) (guide)

- Fabronia ciliaris (Fringed Fabronia) (guide)

- Falco peregrinus (Peregrine Falcon) (guide)

- Gentianopsis virgata (Lesser Fringed Gentian) (guide)

- Halenia deflexa (Spurred Gentian) (guide)

- Lysimachia quadriflora (Linear-leaved Loosestrife) (guide)

- Myotis leibii (Eastern Small-footed Myotis) (guide)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) (guide)

- Myriopteris lanosa (Woolly Lip Fern) (guide)

- Myurella julacea (Small Mousetail Moss) (guide)

- Panicum flexile (Wiry Witch Grass) (guide)

- Pellaea glabella ssp. glabella (Smooth Cliffbrake) (guide)

- Philonotis capillaris (Hairy Apple Moss) (guide)

- Pinguicula vulgaris (Butterwort) (guide)

- Platydictya jungermannioides (False Willow Moss) (guide)

- Primula mistassinica (Bird's Eye Primrose) (guide)

- Pseudocalliergon turgescens (Curving Feather Moss) (guide)

- Rhodiola rosea (Common Roseroot) (guide)

- Saxifraga aizoides (Yellow Mountain Saxifrage) (guide)

- Saxifraga paniculata ssp. paniculata (White Mountain Saxifrage) (guide)

- Schwetschkeopsis fabronia (False Hair Moss) (guide)

- Tomostima reptans (Carolina Whitlow Grass) (guide)

- Woodsia glabella (Smooth Cliff Fern) (guide)

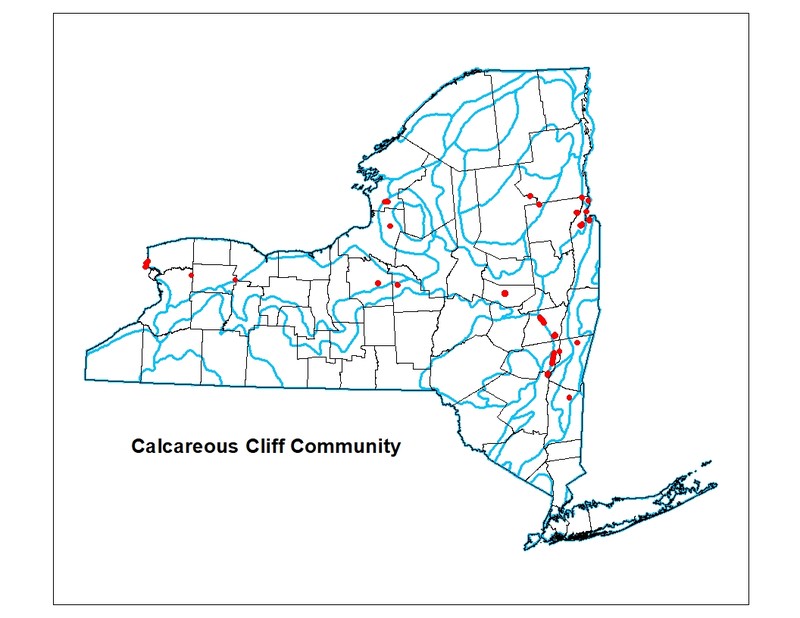

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is widespread throughout upstate New York, north of the North Atlantic Coast Ecoregion, where the bedrock is calcareous. This community is currently known from western New York within the Erie and Ontario Lake Plain (Niagara Escarpment), in central New York north of the Finger Lakes, and in the Mohawk and upper Hudson Valley (Helderberg Escarpment) and Taconic Foothills. Calcareous cliffs are also known from the Central Adirondack Mountains and Eastern Adirondack Low Mountains (Lake George Valley). Additional occurrences may be located elsewhere in the state where similar environmental conditions exist.

Global Distribution

This physically broadly-defined community may be worldwide, where the bedrock is calcareous. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are estimated to span north to southern Canada, west to Minnesota, southwest to Indiana and Tennessee, southeast to North Carolina, and northeast to Nova Scotia.

Best Places to See

- John Boyd Thacher State Park

- East Bay Wildlife Management Area (Washington County)

- Whirlpool State Park (Niagara County)

- Lake George Wild Forest, Adirondack Park (Warren County)

- Devils Hole State Park (Niagara County)

- Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve

- Chittenango Falls State Park (Madison County)

Identification Comments

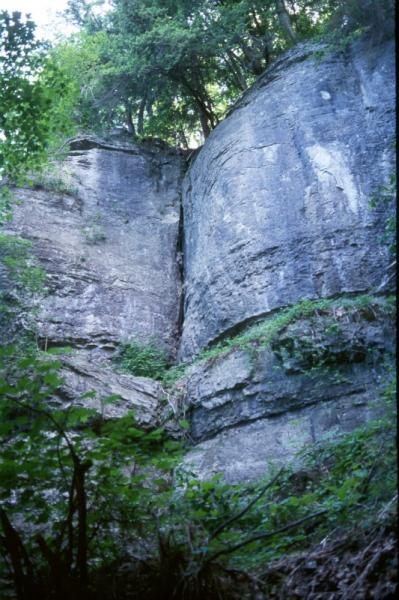

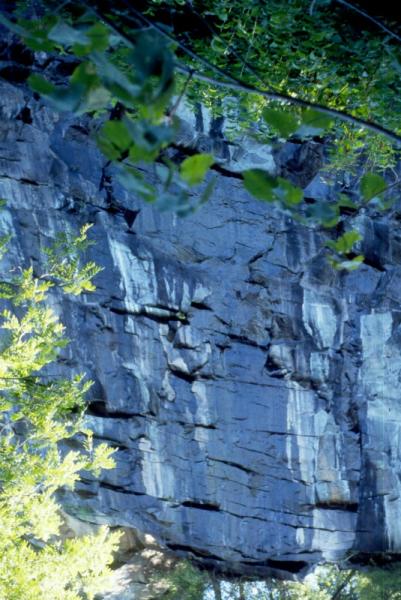

General Description

A community that occurs on vertical exposures of resistant, calcareous bedrock (such as limestone or dolomite) or consolidated material; these cliffs often include ledges and small areas of talus. There is minimal soil development, and vegetation is usually sparse. Plant species present are somewhat dependent on the microclimate conditions, which can range from shady and moist to sun-exposed and dry. Vegetation often inhabits shallow pockets of soil that accumulate on ledges, and in cracks and crevices within the cliff wall. Different types of calcareous cliffs may be distinguished based on exposure and moisture. Under shaded conditions bryophyte diversity is high, and cool, moist cliff faces can support a variety of plant species similar in composition to the surrounding forest. Exposed cliffs are more sparsely vegetated and plants are typically found rooted in small amounts of soil that accumulates on ledges, or in cracks and crevices.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic small trees and shrubs include eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), hop hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), round-leaf dogwood (Cornus rugosa), Canada yew (Taxus canadensis), black cherry (Prunus serotina), downy arrow-wood (Viburnum rafinesquianum), and northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis). Characteristic herbs growing in cracks and on ledges include bulblet fern (Cystopteris bulbifera), bristleleaf sedge (Carex eburnea), herb robert (Geranium robertianum), zig-zag goldenrod (Solidago flexicaulis), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), purple cliff brake (Pellaea atropurpurea), early saxifrage (Saxifraga virginiensis), and wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis). Characteristic calcareous cliff mosses include Anomodon attenuatus, A. rostratus, A. viticulosus, Encalypta procera, Fissidens bryoides, Gymnostomum aeruginosum, Myurella siberica, and Tortella tortuosa. The rare small mousetail moss (Myurella julacea), false willow moss (Platydictya jungermannioides), and chalk dwarf moss (Seligeria calcarea) are known from calcareous cliff communities.

Best Time to See

From mid to late spring, red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) comes into bloom, making calcareous cliff communities that harbor this species very scenic. Throughout the summer, other attractive wildflowers, such as herb-robert (Geranium robertianum), American harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), and ferns such as bulblet fern (Cystopteris bulbifera), can be seen.

Calcareous Cliff Community Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Single-spike Sedge Alkaline Cliff Vegetation (CEGL006526)

- Purple Cliffbrake Cliff Sparse Vegetation (CEGL006527)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Laurentian-Acadian Calcareous Cliff and Talus (CES201.570)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Carya glabra (pignut hickory)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Thuja occidentalis (northern white cedar, arbor vitae)

- Tilia americana var. americana (American basswood)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Celtis occidentalis (northern hackberry)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Cornus rugosa (round-leaved dogwood)

- Dasiphora fruticosa (shrubby-cinquefoil)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Rhus aromatica var. aromatica (fragrant sumac)

- Ribes cynosbati (prickly gooseberry, dogberry)

- Rubus odoratus (purple-flowering raspberry)

- Staphylea trifolia (bladdernut)

- Taxus canadensis (Canada yew, American yew)

- Viburnum rafinesqueanum (downy arrowwood)

-

Vines

- Celastrus scandens (American bittersweet)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Aquilegia canadensis (wild columbine, red columbine)

- Asplenium rhizophyllum (walking fern)

- Asplenium ruta-muraria (wall-rue)

- Asplenium trichomanes ssp. trichomanes (maidenhair spleenwort)

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Campanula rotundifolia (hare-bell)

- Carex eburnea (bristle-leaved sedge)

- Carex platyphylla (broad-leaved sedge)

- Cystopteris bulbifera (bulblet fern)

- Geranium robertianum (herb-Robert)

- Lobelia kalmii (Kalm's lobelia)

- Menispermum canadense (moonseed)

- Micranthes virginiensis (early-saxifrage)

- Pellaea atropurpurea (purple cliff-brake)

- Pellaea glabella ssp. glabella (smooth cliff-brake)

- Poa compressa (flat-stemmed blue grass, Canada blue grass)

- Schizachne purpurascens (false melic grass)

- Solidago flexicaulis (zig-zag goldenrod)

- Solidago ptarmicoides (upland white flat-topped-goldenrod)

- Thalictrum dioicum (early meadow-rue)

- Thalictrum thalictroides (rue-anemone)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Anomodon attenuatus

- Anomodon rostratus

- Encalypta procera

- Gymnostomum aeruginosum

- Tortella tortuosa

Similar Ecological Communities

- Calcareous talus slope woodland

(guide)

While both communities occur on calcareous rock such as limestone or dolomite, calcareous cliff communities tend to be steeper and usually sparsely vegetated, and typically have very few to no trees. Whereas, calcareous talus slope woodlands are not as steep and have at least 25% cover of trees. Calcareous talus slope woodlands often occur at the base of calcareous cliffs.

- Cliff community

(guide)

Cliff communities have shallow soils and sparse vegetation, but they occur on vertical exposures of non-calcareous bedrock types, such as quartzite, sandstone, or schist.

- Shale cliff and talus community

(guide)

Shale cliff and talus communities occur on vertical, and nearly vertical exposures of shale bedrock, and include areas of talus. Limestone shale cliffs support species associations that are very similar to the calcareous cliff community.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Calcareous Cliff Community. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Kelly, P. E., and D. W. Larson. 1997. Dendroecological analysis of the population dynamics of an old-growth forest on cliff-faces of the Niagara Escarpment, Canada. Journal of Ecology 85:467-478.

Larson, D.W. 1989. Effects of disturbance on old-growth Thuja occidentalis at cliff edges. Can. J. Bot. 68:1147-155.

Larson, D.W., U. Matthes, and P.E. Kelly. 2000. Cliff Ecology: Pattern and Process in Cliff Ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, New York, New York.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Van Diver, Bradford B. 1985. Roadside Geology of New York. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, MT.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: January 23, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Calcareous cliff community.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/calcareous-cliff-community/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.