Maritime Dunes

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Unlike most terrestrial systems, maritime dune systems move over the landscape and even across property boundaries. Consequently, this migrating dune system is difficult to preserve. However, it needs to be protected and restored. A healthy dune system protects property by reducing the energy of storm waves. It is the best defense against coastal flooding, erosion, and sea-level rise. It provides tremendous economic benefit to the local economy. A healthy coastal sand dune system is also the least costly way to maintain a recreational beach for future generations. (http://www.maine.gov/dep/blwq/topic/dunes/)

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 130 miles of maritime dunes on Long Island (about 100 miles on the south shore) covering about 4,700 to 14,000 acres; there may be as many as 30 to 50 extant occurrences statewide. The several documented occurrences have good viability and most are protected on public or private conservation land. This community is restricted to the ocean shoreline of southern and eastern Long Island and includes some high quality examples. The trend for the community is declining due to threats related to alteration of dune/swale dynamics, including management practices that alter natural hydrologic processes (such as breach contingency plans), dune fragmentation, loss of connectivity between the open ocean and the uplands, ORV use, and coastal development.

Short-term Trends

Although the number of maritime dunes may have increased slightly when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development, the acreage of maritime dunes in New York has probably declined in recent decades as a result of coastal development and recreational overuse. Community viability/ecological integrity is suspected to be slowly declining, primarily due to anthropogenic alterations (both physical and hydrological) to dune and swale dynamics and coastal development (e.g., fragmentation, shoreline hardening, filling, road construction, and community destruction).

Long-term Trends

Although the number of maritime dunes in New York may have increased substantially from historical numbers when formerly long, continuous examples were fragmented by development into numerous large and small stretches of dunes, their aerial extent and viability are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in connectivity, hydrology, water quality, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Breach contingency plans for public lands that include dune stabilization and repair, draining overwash water, and other hydrologic alterations threaten processes that create and maintain the community. Additional threats include fragmentation of dunes by development, barriers to connectivity between the open ocean and the dunes, driving on the dunes (off-road and four-wheel drive vehicles), trampling, and invasion by exotic species (Elaeagnus umbellata, Celastrus orbiculata, Pinus thunbergii, Rosa rugosa, Lonicera japonica, Carex kobomugi, and Phragmites australis).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Maintain dynamic beach and dune processes, including allowing dunes to be breached and overwashed by storm events. Minimize breach closure, groundwater pollution, and road fill. Prevent recreational overuse (e.g., driving and trampling) and encourage the public to stay on marked trails. Undertake dune restoration using native species as needed and avoid planting potential invasives, like Rosa rugosa. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the dunes through appropriate direct management and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as beach access trails and roads. Monitor the nesting use of dunes by species such as the diamondback terrapin and take measures (e.g., install predator exclosures) to prevent nest predation by raccoons, skunks, and foxes. Ensure connectivity between maritime dunes, low salt marsh, and the open ocean to allow species to freely move between habitats during nesting season.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Any development effort that disrupts connectivity between the open ocean and the maritime dune system should be avoided (e.g., a road running parallel to the beach between the beach and dunes). This community is best protected as part of a large beach, dune, salt marsh complex. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow dynamic ecological processes (overwash, erosion, and migration) to continue. Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities, upland beaches and dunes, and to shallow offshore communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Similarly, fragmentation of linear dune systems should be avoided. Bisecting trails, roads, and developments allow exotic species to invade, potentially increase 'edge species' (such as raccoons, skunks, and foxes), and disrupt physical dune processes.

Inventory Needs

Surveys and documentation of additional occurrences are needed, as are data on rare and characteristic animals.

Research Needs

An investigation into the taxonomic distinction between the stabilized maritime dune variant, maritime heathland, and maritime grassland is needed, as these communities can be essentially identical in species composition, structure, and function. They need further documentation, analysis, and clarification. More research could focus on site specific habitat suitability and use for nesting by terrapins, seabirds, and other species.

Rare Species

- Abagrotis benjamini (Coastal Heathland Cutworm) (guide)

- Apamea burgessi (Burgess's Apamea) (guide)

- Apamea inordinata (Irregular Apamea) (guide)

- Ardea alba (Great Egret) (guide)

- Carex hormathodes (Marsh Straw Sedge) (guide)

- Cenchrus tribuloides (Dune Sandspur) (guide)

- Charadrius melodus (Piping Plover) (guide)

- Chordeiles minor (Common Nighthawk) (guide)

- Cicindela hirticollis (Hairy-necked Tiger Beetle) (guide)

- Coelodasys apicalis (Plain Schizura) (guide)

- Cyperus retrorsus var. retrorsus (Retrorse Flatsedge) (guide)

- Cyperus schweinitzii (Schweinitz's Flat Sedge) (guide)

- Derrima stellata (Pink Star Moth) (guide)

- Dichagyris acclivis (Switchgrass Dart) (guide)

- Eacles imperialis imperialis (Imperial Moth) (guide)

- Eupatorium pubescens (Hairy Thoroughwort) (guide)

- Eupatorium torreyanum (Torrey's Thoroughwort) (guide)

- Euxoa pleuritica (Fawn Brown Dart) (guide)

- Euxoa violaris (Violet Dart) (guide)

- Gelochelidon nilotica (Gull-billed Tern) (guide)

- Hypomecis umbrosaria (Umber Moth) (guide)

- Ilexia intractata (Black-dotted Ruddy) (guide)

- Linum intercursum (Sandplain Wild Flax) (guide)

- Marimatha nigrofimbria (Black-bordered Lemon Moth) (guide)

- Nyctanassa violacea (Yellow-crowned Night-Heron) (guide)

- Oenothera oakesiana (Oakes' Evening Primrose) (guide)

- Oligia bridghamii (Bridgham's Brocade) (guide)

- Parasa indetermina (Stinging Rose Caterpillar Moth) (guide)

- Plantago maritima var. juncoides (Seaside Plantain) (guide)

- Platanthera cristata (Orange Crested Orchid) (guide)

- Polygonum buxiforme (American Knotweed) (guide)

- Polygonum glaucum (Seabeach Knotweed) (guide)

- Pycnanthemum muticum (Blunt Mountain Mint) (guide)

- Renia nemoralis (Chocolate Renia) (guide)

- Spiranthes vernalis (Grass-leaved Ladies' Tresses) (guide)

- Sterna dougallii (Roseate Tern) (guide)

- Sterna hirundo (Common Tern) (guide)

- Sternula antillarum (Least Tern) (guide)

- Sympistis riparia (Dune Sympistis) (guide)

- Tripsacum dactyloides (Northern Gama Grass) (guide)

- Viburnum dentatum var. venosum (Southern Arrowwood) (guide)

Range

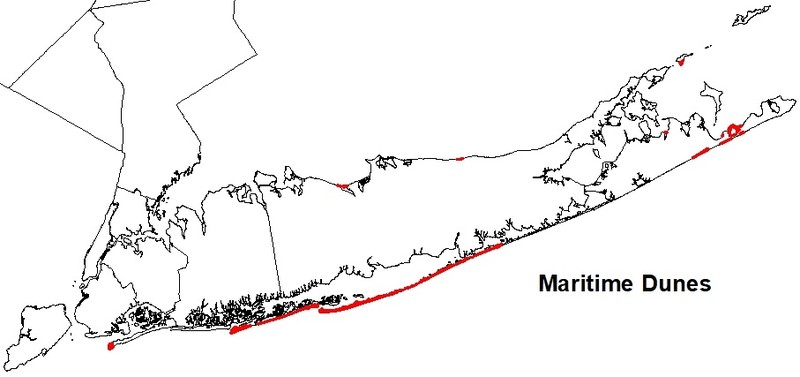

New York State Distribution

Restricted to the ocean shoreline of southern and eastern Long Island. Discontinuous patches of maritime dunes occur from Rockaway Point east to Jones Beach, where the dunes become larger and less fragmented (e.g., Fire Island Wilderness Area), and the dunes continue east until the shore grades into morainal bluffs at Montauk Point. Smaller examples (<5 miles long each) occur in the Peconic Bay and along the north shore of the North Fork of Long Island.

Global Distribution

This community is restricted to mainland coastal, barrier island, and peninsular sand dunes along the northern Atlantic Coast from Maine south to North Carolina (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Jones Beach State Park (Nassau County)

- Gateway National Recreation Area - Breezy Point (Queens County)

- Hither Hills State Park (Suffolk County)

- Fire Island National Seashore (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A community dominated by grasses and low shrubs that occurs on active and stabilized dunes along the Atlantic coast. This community consists of a mosaic of vegetation patches. This mosaic reflects past natural disturbances such as sand deposition, erosion, and dune migration. The composition and structure of the vegetation is variable depending on stability of the dunes, amounts of sand deposition and erosion, and distance from the ocean.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic species of the active dunes, where sand movement is greastest, include American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), dusty-miller (Artemisia stelleriana), beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus), sedge (Carex silicea), seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), and sand-rose (Rosa rugosa). Characteristic species of stabilized dunes include beach heather (Hudsonia tomentosa), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), cyperus (Cyperus polystachyos var. macrostachyus), seaside goldenrod, beach pinweed (Lechea maritima), jointweed (Polygonella articulata), common evening-primrose (Oenothera biennis), sand-rose (Rosa rugosa), bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), beach-plum (Prunus maritima), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and the lichens Cladonia submitis and Cetraria arenaria. Seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus) is a federally threatened plant that is found on open sand at the base of the foredune of some maritime dunes. A few stunted pitch pines (Pinus rigida) or post oaks (Quercus stellata) may be present in the dunes.

Best Time to See

The best time to visit maritime dunes is in the mid- to late summer when dune plants are flowering and the water of the Atlantic ocean has warmed to a comfortable temperature for swimming.

Maritime Dunes Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- American Beachgrass - Beach Pea Grassland (CEGL006274)

- Woolly Beach-heather - Bearberry Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006143)

- (Northern Bayberry) / Shore Little Bluestem - Seaside Three-awn Shrub Grassland (CEGL006161)

- Cat Greenbrier - Eastern Poison-ivy Vine-Shrubland (CEGL003886)

- Saltmeadow Cordgrass - Common Threesquare - Seaside Goldenrod Grassland (CEGL004097)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dune and Swale (CES203.264)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (bearberry)

- Hudsonia tomentosa (beach-heather)

- Iva frutescens (salt marsh-elder)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Prunus maritima (beach plum)

- Rosa rugosa (Japanese rose)

- Rubus allegheniensis (common blackberry)

- Rubus flagellaris (northern dewberry)

-

Tree saplings

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Vines

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Smilax rotundifolia (common greenbrier)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Ammophila breviligulata ssp. breviligulata

- Artemisia stelleriana (beach wormwood, dusty miller)

- Cakile edentula var. edentula (American sea rocket)

- Carex silicea (beach sedge)

- Chamaesyce polygonifolia

- Chrysopsis mariana (Maryland golden-aster)

- Cyperus polystachyos (many-spiked flat sedge)

- Eragrostis spectabilis (purple love grass)

- Lathyrus japonicus var. maritimus (beach-pea)

- Lechea maritima var. maritima (beach pinweed)

- Oenothera biennis (common evening-primrose)

- Panicum virgatum (switch grass)

- Polygonum articulatum (northern jointweed)

- Schizachyrium scoparium var. scoparium (little bluestem)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

-

Nonvascular plants

- dune reindeer lichen (Cladonia submitis)

- sand-loving Iceland lichen (Cetraria arenaria)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Great Lakes dunes

(guide)

Great Lakes dunes and martime dunes share many plant species and experience similar disturbance regimes, but Great Lakes dunes are located on the shores of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Maritime dunes are typically much larger due to the strength and duration of ocean winds.

- Maritime grassland

(guide)

Maritime dunes occur on active and stabilized sand dunes along the Atlantic coast. Active dunes are characterized by a near monoculture of beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata) and more stable areas can support a variety of species, some of which (like little bluestem) can also be found in maritime grasslands. Maritime grasslands are located on the deeper soils of rolling outwash plains (not on sandy dunes) further from the ocean but still within the range of offshore winds and salt spray. They are characterized by the grasses little bluestem, common hairgrass, and poverty-grass.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Dunes. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Andrle, Robert F. and Janet R. Carroll, editors. 1988. The atlas of breeding birds in New York State. Cornell University Press. 551 pp.

Art, H. W. 1976. Ecological studies of the Sunken Forest, Fire Island National Seashore, New York. National Park Service Scientific Monograph Series No. 7, Publication No. NPS 123. 237 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Hancock, T.E. 1995. Ecology of the threatened species seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus Rafinesque). Masters Thesis. Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, N.C.

Johnson, Anne F. 1985. A guide to the plant communities of the Napeague dunes Long Island, New York. Mad Printers, Mattituck, New York. 58 pp.

Leatherman, S.P. 1979. Effects of off-road vehicles on the geomorphology of dunes in Cape Cod National Park. National Park Service Transactions and Proceedings Series. Number 5, pp. 1119-1124.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Packham, J.R. and A.J. Willis. 1997. Ecology of Dunes, Salt Marsh and Shingle. Chapman and Hall, London.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Robichaud, B. and M.F. Buell. 1973. Vegetation of New Jersey: A study of landscape diversity. Rutgers Univ. Press. New Brunswick, NJ. 340 pp.

Schlesinger, M.D., E.L. White, S.M. Young, G.J. Edinger, K.A. Perkins, N. Schoppmann, and D. Parry. 2016. Biodiversity Inventory of Plum Island, New York. New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany, New York, and SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime dunes.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-dunes/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.