Spruce-Fir Swamp

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Forested Mineral Soil Wetlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Red spruce is the common dominant in spruce-fir swamps. However, in the Adirondacks black spruce may replace red spruce as the dominant tree. In areas where red spruce and black spruce inhabit the same community, the two may hybridize. Black spruce is distinguishable from red spruce by its smaller dull gray cones on short stalks, which curve downward and remain attached.

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is widespread throughout the northern half of New York, and includes a few large, high quality, old-growth examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include logging, alteration of the natural hydrology, and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of spruce-fir swamps in New York have probably declined slightly, or remained stable, in recent decades as a result of wetland protection regulations.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of spruce-fir swamps in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with logging, agricultural, and development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Spruce-fir swamps are threatened by development (e.g., agriculture, residential, roads, mining operations), habitat alteration (e.g., excessive logging, ditching, filling, pollution/nutrient run-off, plantations), and recreational overuse (e.g., hiking trails, ATVs). Alteration to the natural hydrological regime is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, blocked culverts, beaver). Spruce-fir swamps may be threatened by spruce decline due to acid rain deposition in high elevation examples (US EPA 2005). A few spruce-fir swamps are threatened by invasive species, such as reedgrass (Phragmites australis). Spruce budworm may be considered a threat to occurrences of spruce-fir swamp that experience extreme outbreaks, especially if it coincides with other stresses and reduces tree regeneration. The spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) is a native insect that creates canopy gaps in spruce and fir forests of the Eastern United States and Canada. Since 1909, there have been waves of budworm out breaks throughout the Eastern United States and Canada. The states most often affected are Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin (Kucera and Orr 1981). Balsam fir is the is the primary host tree for budworm in the Eastern United States, although white, red, and black spruce are known to be suitable host trees. Spruce budworm may also feed on tamarack, pine, and hemlock. Spruce mixed with balsam fir is more likely to show signs of budworm infestation than spruce in pure stands (Kucera and Orr 1981).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads. Develop a plan to control or eliminate spruce budworm at sites where it is a problem.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of spruce-fir swamps. A statewide review of spruce-fir swamps is desirable. Continue searching for large sites in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Regularly assess the presence and degree of impact that spruce budworm has on this community. Research composition of spruce-fir swamps statewide in order to characterize variations. Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct spruce-fir swamp types based on composition and by ecoregion. For example, southern New York examples tend to lack balsam fir (Abies balsamea). Confirm the identification and the dominance of red spruce (Picea rubens) vs. black spruce (P. mariana) at all sites.

Rare Species

- Carex arcta (Northern Clustered Sedge) (guide)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Bald Eagle) (guide)

- Neottia auriculata (Auricled Twayblade) (guide)

- Polemonium vanbruntiae (Jacob's Ladder) (guide)

- Pyrola asarifolia ssp. asarifolia (Pink Shinleaf) (guide)

- Sylvilagus transitionalis (New England Cottontail) (guide)

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is widespread throughout the northern half of New York. It is concentrated in the Adirondack Subsection of the Northern Appalachian Ecoregion where it reaches large patch size. Scattered small patch examples occur in the Great Lakes, Lower New England (e.g., Rensselaer Plateau), and High Allegheny Plateau (e.g., probably the Catskill Mountains and Southern Tier) Ecoregions, as well as the Tug Hill section of the Northern Appalachian Ecoregion.

Global Distribution

The range of this community is estimated to span northeast to Nova Scotia, northwest possibly to Ontario, southwest possibly to Pennsylvania, and southeast to the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts and the Rensselaer Plateau of New York.

Best Places to See

- Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area (Lewis County)

- Adirondack Park (St. Lawrence County)

- Catskill Park (Ulster County)

- Appalachian National Scenic Trail (Orange County)

- Capital District Wildlife Management Area (Rensselaer County)

- Littlejohn Wildlife Management Area (Oswego County)

Identification Comments

General Description

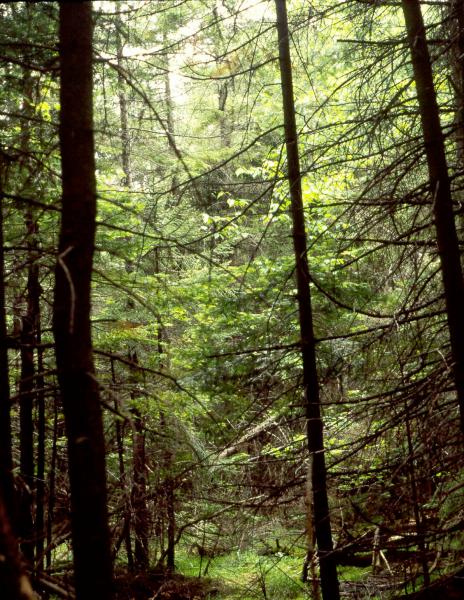

A conifer swamp with little to no peat development that typically occurs in a drainage basin, at the edge of a lake or pond, or along gentle slopes of islands where there is some nutrient input from groundwater discharge or subsurface flow. These swamps are usually dense, with a fairly closed canopy (80 to 90% cover). The dominant tree is usually red spruce. Codominant trees include balsam fir and red maple. In the Catskills, balsam fir may be absent, and in the Adirondacks, black spruce or white spruce may replace red spruce as a dominant tree. The shrub layer is often sparse; characteristic and dominant shrubs include mountain holly and sapling canopy trees. Cinnamon fern is a characteristic herb and patches of peat mosses can be common.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A conifer swamp with dense canopy cover that is dominated by red spruce. Common codominant trees include balsam fir and red maple.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 448 feet and 4,576 feet.

Best Time to See

The striking evergreen canopy of a spruce-fir swamp can be enjoyed year-round, but the community is most lush in mid to late summer when the ferns and mosses are at their peak.

Spruce-Fir Swamp Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Red Spruce - Balsam Fir / Creeping Snowberry / Cinnamon Fern / Peatmoss species Swamp Forest (CEGL006312)

- Red Spruce - Red Maple / Catberry Swamp Forest (CEGL006198)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Appalachian-Acadian Conifer-Hardwood Acidic Swamp (CES201.574)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)

- Larix laricina (tamarack)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

- Picea rubens (red spruce)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

- Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Ilex verticillata (common winterberry)

- Sorbus americana (American mountain-ash)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

-

Herbs

- Carex trisperma (three-fruited sedge)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Lysimachia borealis (starflower)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. cinnamomeum (cinnamon fern)

- Oxalis montana (northern wood sorrel)

- Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens (marsh fern)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Bazzania trilobata

- Sphagnum magellanicum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Balsam flats

(guide)

Spruce-fir swamps are located at lower elevations than balsam flats, which are dominated by balsam fir; the swamps also have wetland soils and patches of peat mosses. Black cherry, a characteristic species of balsam flats, is notably absent from spruce-fir swamps.

- Black spruce-tamarack bog

(guide)

Black spruce-tamarack bogs are distinguished from spruce-fir swamps by having a peat substrate (instead of mineral soil) and a combined tree and tall shrub cover of tamarack and black spruce that is greater than that of balsam fir and red spruce.

- Northern white cedar swamp

(guide)

Spruce-fir swamps are distinguished from northern white cedar swamps by having predominately mineral soils and a combined tree and tall shrub cover of balsam fir and red spruce that is greater than that of northern white cedar and black ash.

- Spruce flats

(guide)

Spruce-fir swamps are located at lower elevations than spruce flats, which are dominated by red spruce and red maple; the swamps also have wetland soils and patches of peat mosses. Black cherry, a characteristic species of spruce flats, is notably absent from spruce-fir swamps.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Spruce-Fir Swamp. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Braun, E. Lucy. 1950. Deciduous forests of Eastern North America. Macmillan Publ. Co. Inc., New York, N.Y.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Kucera, D.R. and P.W. Orr. 1981. Spruce budworm in the eastern United States. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 160. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. No date. Field forms database: Electronic field data storage and access for New York Heritage ecology, botany, and zoology. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

United States Envoronmental Protection Agency. 2005. Effects of Acid Rain: Forests. Available on line at http:www.epa.gov/airmarkets/acidrain/effects/forests.html Accessed March 2, 2005.

Zon, R. 1914. Balsam fir. Bull. U.S. Department Agriculture No. 55:1-68.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: November 13, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Spruce-fir swamp.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/spruce-fir-swamp/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.