Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Forested Peatlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4G5

Apparently or Demonstrably Secure globally - Uncommon to common in the world, but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G4 or G5.

Summary

Did you know?

The common name for the tamarack comes from the Algonquian Native American name that means "wood used for snowshoes." Other Algonquian names that are used in English are mainly animals such as caribou, moose, chipmunk, raccoon, muskrat, opossum, woodchuck, and skunk and plants such as hickory and pecan.

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has a limited distribution to the northern half of the state, and includes several very large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure or alteration to the natural hydrology. This community has declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with peat mining and logging and development of the surrounding landscape.

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of black spruce-tamarack bogs in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of wetland protection regulations. There may be a few cases of slight decline due to alteration of hydrology from impoundments (conversion to other palustrine community types).

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of black spruce-tamarack bogs in New York have probably declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with initial peat mining and logging of the surrounding landscape (increasing nutrient run-off into bogs).

Conservation and Management

Threats

Black spruce-tamarack bogs are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., agricultural, roads, railroads), recreational overuse (e.g., hiking trails causing peat compaction), and habitat alteration in the adjacent landscape (e.g., mining, excessive logging, pollution, nutrient loading). Alteration to the natural hydrology is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, blocked culverts, beaver). Several examples of black spruce-tamarack bog are threatened by invasive species, such as reedgrass (Phragmites australis).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Because black spruce-tamarack bogs are naturally acidic and low in nutients, they are particularly susceptible to alteration by elevated nutrient inputs. Bogs may require larger buffers than other wetland types because of their high susceptibility to changes in nutrient concentrations. Direct impacts are typically most serious within 300 feet (90 m) of wetland areas (Sperduto et al. 2000).

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of peatlands. A statewide review of the acidic peatlands is desirable, similar to the studies done in New Hampshire (Sperduto et al. 2000), Massachusetts (Kearsley 1999), and similar to what New York Natural Heritage did for rich fens (Olivero 2001).

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about black spruce-tamarack bogs, especially to advance our understanding of their classification, ecological processes (e.g., fire), hydrology, floristic variation, characteristic fauna, and bog development and succession. This research will provide the basic facts necessary to assess how human alterations in the landscape affect peatlands, and supply a framework for evaluating the relative value of peat bogs (Damman and French 1987).

Rare Species

- Aeshna subarctica (Subarctic Darner) (guide)

- Betula pumila (Swamp Birch) (guide)

- Calypso bulbosa var. americana (Calypso) (guide)

- Carex wiegandii (Wiegand's Sedge) (guide)

- Criorhina nigriventris (Bare-cheeked Bumblefly) (guide)

- Euphagus carolinus (Rusty Blackbird) (guide)

- Glyptemys muhlenbergii (Bog Turtle) (guide)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Bald Eagle) (guide)

- Neottia bifolia (Southern Twayblade) (guide)

- Pyrola asarifolia ssp. asarifolia (Pink Shinleaf) (guide)

- Salix pyrifolia (Balsam Willow) (guide)

- Scheuchzeria palustris (Pod Grass) (guide)

- Sistrurus catenatus (Eastern Massasauga) (guide)

- Somatochlora cingulata (Lake Emerald) (guide)

- Somatochlora forcipata (Forcipate Emerald) (guide)

- Somatochlora incurvata (Incurvate Emerald) (guide)

- Vermivora chrysoptera (Golden-winged Warbler) (guide)

Range

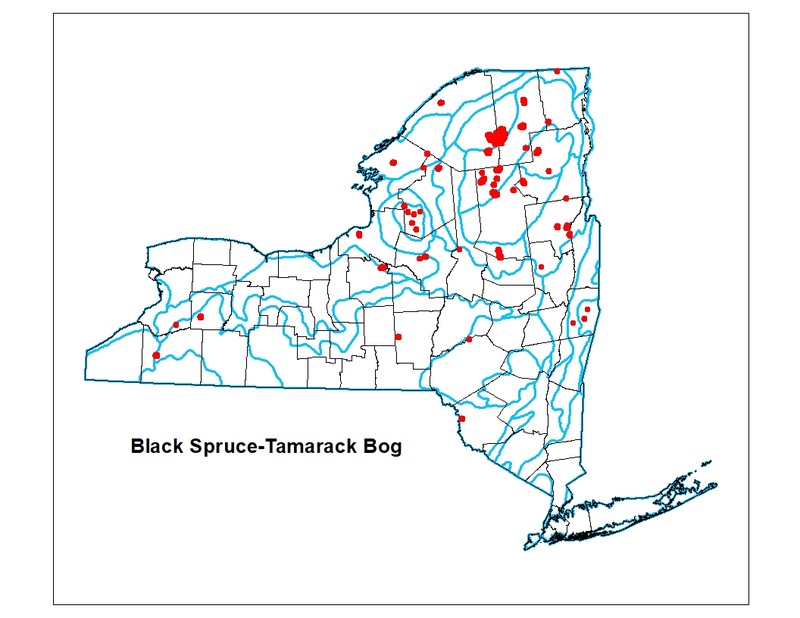

New York State Distribution

This community is found primarily in the northern half of the state. It is concentrated in the Adirondacks, but is also common in the Great Lakes area. There are very small, scattered examples in the lower Hudson, Tug Hill Plateau, and possibly also the Alleghany area.

Global Distribution

The range is probably widespread throughout Canada and along the northeastern fringe of the United States. The range is estimated to span northeast to Newfoundland, northwest possibly to northwestern Canada, west to Minnesota, southwest to Michigan, and southeast to Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and possibly New Jersey.

Best Places to See

- Perch River Wildlife Management Area (Jefferson County)

- Cicero Swamp Wildlife Management Area (Onondaga County)

- Silver Lake Bog Preserve (Clinton County)

- Paul Smith's College Visitor Information Center (VIC) (Franklin County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A conifer forest that occurs on acidic peatlands in cool, poorly drained depressions. The characteristic trees are black spruce (Picea mariana) and tamarack (Larix laricina); in any one stand, either tree may be dominant, or codominant. Canopy cover is quite variable, ranging from open canopy woodlands with as little as 20% cover of evenly spaced canopy trees to closed canopy forests with 80 to 90% cover. In the more open canopy stands there is usually a well-developed shrub layer characterized by several shrubs typical of bogs including sheep laurel (Kalmia angustifolia), Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), mountain holly (Nemopathus mucronatus) and highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). In closed canopy stands the shrub layer is usually sparse; however the species composition is similar. The dominant groundcover consists of several species of Sphagnum moss with scattered sedges and forbs. Vascular plant diversity is usually low in these forested peatlands; however the bryophyte and epiphytic lichen flora may be relatively diverse. Characteristic herbs are three-seeded sedge (Carex trisperma), cotton grass (Eriophorum spp.), pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea), cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), and in shady areas where the canopy is dense, gold thread (Coptis trifolia) and creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula). A black spruce-tamarack bog may imperceptibly grade into and form a mosaic with a dwarf shrub bog. As the peat substrate thins and the wetland transitions to terrestrial communities, the black spruce-tamarack bog may grade into spruce flats.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A conifer dominated, peatland swamp forest dominated by black spruce and/or tamarack. Typically the dominant species have >50% combined cover in the canopy, sub-canopy and tall shrub layers.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 318 feet and 2,034 feet.

Best Time to See

Open canopy stands with a well-developed bog shrub layer are particularly lovely beginning in late May and continuing through June, when the characteristic shrubs are in full bloom.

Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Black Spruce - (Tamarack) / Bog Labrador-tea / Peatmoss species Swamp Forest (CEGL005271)

- Black Spruce / Bog Labrador-tea / Three-seeded Sedge / Peatmoss species Treed Bog (CEGL002485)

- Black Spruce / (Highbush Blueberry, Black Huckleberry) / Peatmoss species Swamp Woodland (CEGL006098)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- North-Central Interior and Appalachian Acidic Peatland (CES202.606)

- Northern Appalachian-Acadian Conifer-Hardwood Acidic Swamp (CES201.574)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Larix laricina (tamarack)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Ilex mucronata (mountain holly)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

- Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides (northern wild-raisin)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf)

- Kalmia angustifolia var. angustifolia (sheep laurel, sheep-kill)

- Kalmia polifolia (bog laurel)

- Rhododendron groenlandicum (Labrador-tea)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium myrtilloides (velvet-leaved blueberry)

- Vaccinium oxycoccos (small cranberry)

-

Tree saplings

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Larix laricina (tamarack)

- Picea mariana (black spruce)

-

Herbs

- Carex trisperma (three-fruited sedge)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Eriophorum virginicum (tawny cotton-grass)

- Gaultheria hispidula (snowberry)

- Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. cinnamomeum (cinnamon fern)

- Sarracenia purpurea (purple pitcherplant)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Bazzania trilobata

- Pleurozium schreberi

- Sphagnum angustifolium

- Sphagnum girgensohnii

- Sphagnum magellanicum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Dwarf shrub bog

(guide)

The dominance of low growing shrubs, most commonly leatherleaf, which are typically less than one meter tall, distinguishes dwarf shrub bogs from black spruce-tamarack bogs.

- Red maple-tamarack peat swamp

(guide)

Red maple-tamarack peat swamps are distinguished from black spruce-tamarack bogs by having soils generally rich in calcium, in combination with the presence of red maple as a dominant or co-dominant, while black spruce is absent or present only as a minor associate.

- Spruce-fir swamp

(guide)

Black spruce-tamarack bogs are distinguished from spruce-fir swamps by having a peat substrate >20cm deep (instead of mineral soil or shallow peat) and a combined tree and tall shrub cover of tamarack and black spruce that exceeds that of balsam fir and red spruce.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Damman, A.W.H. and T.W. French. 1987. The ecology of peat bogs of the glaciated northeastern United States: a community profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report 85(7.16). 100 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Kearsley, J. 1999. Non-forested acidic peatlands of Massachusetts: A statewide inventory and vegetation classification. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Westborough, MA.

Langdon, Stephen F., M. Dovciak, and D.J. Leopold. 2020. Tree Encroachment Varies by Plant Community in a Large Boreal Peatland Complex in the Boreal-Temperate Ecotone of Northeastern USA. Wetlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01319-z

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Olivero, Adele M. 2001. Classification and Mapping of New York's Calcareous Fen Communities. A summary report prepared for the Nature Conservancy - Central/Western New York Chapter with funding from the Biodiversity Research Institute. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 28 pp. plus nine appendices.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Sperduto, D.D., W.F. Nichols, and N. Cleavitt. 2000. Bogs and fens of New Hampshire. New Hampshire Natural Heritage Inventory, Concord, New Hampshire.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 14, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Black spruce-tamarack bog.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/black-spruce-tamarack-bog/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.