Maritime Shrubland

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Maritime shrublands generally contain scattered stunted "salt pruned" trees with contorted branches and wilted leaves. When salt spray is blown ashore by strong offshore winds, it blasts against the trees and shrubs that are close to the sea. Their leaves and branches are slowly degraded over time, resulting in a thinned, asymmetrical growth form that appears to lean back away from the ocean.

State Ranking Justification

The several documented occurrences have good viability and are protected on public conservation land. The community is restricted to the seacoast of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in New York in Suffolk, Nassau, Richmond, Queens, and Kings Counties and is concentrated on dry seaside bluffs and headlands that are exposed to offshore winds and salt spray. The trend for the community is declining due primarily to threats from invasive species encroachment and coastal development that fragments maritime systems.

Short-term Trends

Community viability/ecological integrity and area of occupancy is suspected to be slowly declining, primarily due to invasive species proliferation. Coastal development and associated filling, road construction, and community destruction are additional contributing factors.

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of maritime shrubland in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in landscape connectivity and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Maritime shrubland is threatened by the proliferation of invasive exotic vines Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) and Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) are the two most aggressive species and threaten to convert the community to a 'vineland.' Additional exotic species (including Rosa rugosa, Pinus thunbergii, and Elaeagnus umbellata) also threaten community integrity. The community is also vulnerable to fragmentation, degradation, and extirpation from further coastal development, particularly development that separates these shrublands from the maritime influences of offshore winds and salt spray. The spread of hiking and horse trails also fragments the system and threatens community integrity.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Monitor the abundance of invasive species, particularly Oriental bittersweet and Japanese honeysuckle, in this community and, as needed, control their encroachment.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

This community is best protected as part of a large maritime system, encompassing grasslands, shrublands, bluffs, heathland, forests, barrens, and dunes. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow for nutrient flow, seed dispersal, and seasonal animal migrations within them. Bisecting trails, roads, and developments can also allow exotic plant and animal species to invade and potentially increase 'edge species' (such as raccoons, skunks, and foxes). Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities and to shallow offshore communities should also be maintained as much as possible to maintain "maritime" conditions, which imply deposition of salt spray and shearing from offshore winds.

Inventory Needs

Surveys and documentation of additional occurrences are needed, as are data on rare and characteristic animals. Plot data collection from known sites is also needed.

Research Needs

A critical assessment of the long-term effects of Oriental bittersweet and Japanese honeysuckle invasion is needed, particularly addressing whether the community is eventually converted to a "vineland" or whether shrub canopy species are still able to survive and recruit. More research and classification work within possible landscape variants is needed (e.g., maritime shrublands on morainal headland vs. outwash barrier dune) and to possibly recognize "tall" (>2 m) and "short" (<2 m) maritime shrubland variants.

Rare Species

- Agalinis decemloba (Sandplain Agalinis) (guide)

- Amelanchier nantucketensis (Nantucket Juneberry) (guide)

- Arethusa bulbosa (Dragon's Mouth Orchid) (guide)

- Chordeiles minor (Common Nighthawk) (guide)

- Circus hudsonius (Northern Harrier) (guide)

- Crocanthemum dumosum (Bushy Rock Rose) (guide)

- Cyperus retrorsus var. retrorsus (Retrorse Flatsedge) (guide)

- Egretta thula (Snowy Egret) (guide)

- Erechtites hieraciifolius var. megalocarpus (Coastal Fireweed) (guide)

- Iris prismatica (Slender Blue Flag) (guide)

- Juncus scirpoides (Sedge Rush) (guide)

- Linum intercursum (Sandplain Wild Flax) (guide)

- Lysimachia hybrida (Lowland Loosestrife) (guide)

- Nyctanassa violacea (Yellow-crowned Night-Heron) (guide)

- Pycnanthemum muticum (Blunt Mountain Mint) (guide)

- Renia nemoralis (Chocolate Renia) (guide)

- Viburnum dentatum var. venosum (Southern Arrowwood) (guide)

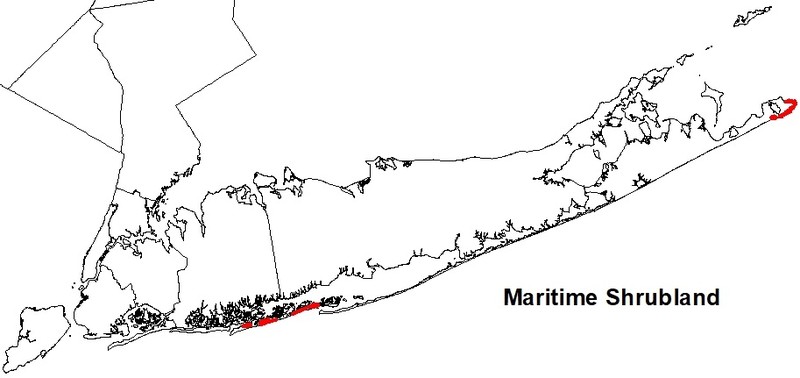

Range

New York State Distribution

Restricted to the seacoast of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in New York in Suffolk, Nassau, Richmond, Queens, and Kings Counties; concentrated on dry seaside bluffs and headlands that are exposed to offshore winds and salt spray.

Global Distribution

This community occurs from Quebec in Canada through Maine to New Jersey (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Montauk Point State Park (Suffolk County)

- Jones Beach State Park (Nassau County)

- Fire Island National Seashore (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A shrubland community that occurs on dry seaside bluffs and headlands that are exposed to onshore winds and salt spray. This community typically occurs as a tall shrubland (2-3 m), but may include areas under 1m shrub height, to areas with shrubs up to 4 m tall forming a shrub canopy in shallow depressions. These low areas may imperceptibly grade into shrub swamp if soils are sufficiently wet. Trees are usually sparse or absent (ideally less than 25% cover). Maritime shublands may form a patchy mosaic and grade into other maritime communities. For example, if trees become more prevalent it may grade into one of the maritime forest communities, such as successional maritime forest. If a severe storm reduces shrub cover and deposits sand into the community it may be converted to a maritime dune. This community shares many shrub species with maritime dunes, but typically lacks the maritime dune herb species.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic shrubs and sapling trees include serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), black cherry (Prunus serotina), southern arrowwood (Viburnum dentatum var. venosum), and shining sumac (Rhus copallinum). Other shrubs and stunted trees include beach-plum (Prunus maritima), sand-rose (Rosa rugosa), wild rose (R. virginiana), eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), American holly (Ilex opaca), black oak (Quercus velutina), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum). Small amounts of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia), red maple (Acer rubrum), and black chokeberry (Photinia melanocarpa) are found in moister low areas, often grading to small patches of shrub swamp. Morrow's honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii) is a common invasive shrub in this community. Characteristic vines include poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quiquefolia), and common greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia). Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) and Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) are common invasive vines in this community. The herb layer is very sparse and may contain a few scattered grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia), wild indigo (Baptisia tinctoria), white-topped aster (Sericocarpus asteroides), and little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium). Birds that may be found in maritime shrublands include black-crowned night-heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), fish crow (Corvus ossifragus), yellow-breasted chat (Icteria virens), and migratory songbirds (especially in fall) (Levine 1998).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 2 feet and 103 feet.

Best Time to See

During the growing season, a characteristic shrub of maritime shrublands, bayberry, produces spicy-smelling fruit. These berries persist on the branches, and can be observed throughout much of the year.

Maritime Shrubland Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Canadian Serviceberry - Viburnum species - Northern Bayberry Scrub Forest (CEGL006379)

- Northern Bayberry - Beach Plum Shrubland (CEGL006295)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dune and Swale (CES203.264)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Pinus thunbergii (Japanese black pine)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry)

- Ilex opaca var. opaca (American holly)

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Prunus maritima (beach plum)

- Rhus copallinum var. copallinum (common winged sumac)

- Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum (smooth arrowwood)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Photinia melanocarpa

- Prunus maritima (beach plum)

- Rhus copallinum var. copallinum (common winged sumac)

- Rosa rugosa (Japanese rose)

- Rubus allegheniensis (common blackberry)

- Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum (smooth arrowwood)

-

Tree saplings

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

-

Vines

- Celastrus orbiculatus (Oriental bittersweet)

- Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle)

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia-creeper)

- Smilax rotundifolia (common greenbrier)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

- Vitis labrusca (fox grape)

-

Herbs

- Achillea millefolium (yarrow)

- Euthamia graminifolia (common flat-topped-goldenrod)

- Phragmites australis (old world reed grass, old world phragmites)

- Schizachyrium scoparium var. scoparium (little bluestem)

- Solidago rugosa var. rugosa (common wrinkle-leaved goldenrod)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Maritime dunes

(guide)

If a severe storm reduces shrub cover and deposits sand into the community it may be converted to a maritime dune. This community shares many shrub species with maritime dunes, but typically lacks the maritime dune herb species.

- Maritime heathland

(guide)

Maritime heathland, unlike maritime shrubland, is characterized by dwarf shrubs, including beach heather, bearberry, blueberry, and black huckleberry. Maritime shrublands are dominated by tall expanses of bayberry, arrowwood, and shadbush shrubs. The two communities grade into each other and are distinguished primarily based on shrub height.

- Salt shrub

(guide)

Salt shrub is an estuarine community, dominated by groundsel-tree and saltmarsh-elder, that occurs at the upper limit of high spring and storm tides. Maritime shrublands, terrestrial communities, are located beyond the range of tidal influence but are exposed to offshore winds and salt spray. Groundsel-tree and saltmarsh-elder would only appear at very low abundance in maritime shrublands.

- Shrub swamp

(guide)

Shrub swamp is a palustrine (wetland) community and low areas of maritime shrubland may imperceptibly grade into shrub swamp if their soils are sufficiently wet.

- Successional maritime forest

(guide)

If the tree species that are associated with maritime shrublands (shadbush, black cherry) become prevalent, a maritime shrubland may grade into a successional maritime forest.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Shrubland. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Clark, J.S. 1986. Coastal forest tree populations in a changing environment, southeastern Long Island, New York. Ecol. Monogr. 56(3): 259-277.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Levine, E. 1998. Bull's birds of New York State. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca, NY.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated October, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Robichaud, B. and M.F. Buell. 1973. Vegetation of New Jersey: A study of landscape diversity. Rutgers Univ. Press. New Brunswick, NJ. 340 pp.

Taylor, Norman. 1923. The vegetation of Long Island, Part I. The vegetation of Montauk: A study of grassland and forest. Memoirs Brooklyn Botanical Garden. 2:1-107.

Thompson, John E. 1997. Ecological communities of the Montauk Peninsula, Suffolk County, New York. Prepared for The Nature Conservancy, Long Island Chapter. April 1997.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime shrubland.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-shrubland/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.