Allegheny Oak Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

American chestnut was a common canopy species in Allegheny Oak Forest prior to the chestnut blight. This blight is caused by a fungal infection introduced from Asia in the late 1800's. Its spread has eliminated American Chestnut from the canopy of eastern North American forests. The species persists as sapling sprouts from the tree bases that fall prey to the fungus before the tree can mature and reproduce, beginning the resprout cycle over and over again.

State Ranking Justification

There are currently fewer than ten sites known in New York with an estimate of several hundred to a couple thousand acres statewide. A few documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has a limited statewide distribution and includes a few large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure and unsustainable logging.

Short-term Trends

The number of and acreage of Allegheny oak forests in New York have been relatively stable in recent decades.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of Allegheny oak forests in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with the onset of agricultural and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to forests in general include changes in land use (e.g., clearing for development), forest fragmentation (e.g., roads), and invasive species (e.g., insects, diseases, and plants). Other threats may include over-browsing by deer, fire suppression, recreational overuse and air pollution (e.g., ozone and acidic deposition). When occurring in expansive forests, the largest threat to the integrity of Allegheny oak forests are activities that fragment the forest landscape into smaller pieces. These activities, such as road building and other development, restrict the movement of species and seeds throughout the entire forest, an effect that often results in loss of those species that require larger blocks of habitat (e.g., black bear, bobcat, certain bird species). Additionally, fragmented forests provide decreased benefits to neighboring societies from services these societies often substantially depend on (e.g., clean water, mitigation of floods and droughts, pollination in agricultural fields, and pest control) (Daily et al. 1997). Development of roads, pipelines, and trails across these oak forests could increase invasives and disturbance of forest interior species. Pesticide control of oak leafshredder (Croesia semipurpurans) which could threaten the community by impacting populations of non-target lepidopterans and possibly other forest insects. Allegheny oak forests may be threatened by the non-native spongy moth (Lymantria dispar). The spongy moth is known to feed on the foliage of hundreds of species of plants in North America but its most common hosts are oaks and aspen. Spongy moth populations are typically eruptive in North America; in any forest stand densities may fluctuate from near 1 egg mass per ha to over 1,000 per ha. When densities reach very high levels, trees may become completely defoliated. Several successive years of defoliation, along with contributions by other biotic and abiotic stress factors, may ultimately result in tree mortality (Liebold 2003, McManus et al. 1980).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain and regenerate the species characteristic of this community. High deer densities have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine & French 1998, Knight 2003). Management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees, shrubs and understory herbaceous species are not so heavily browsed that they cannot reproduce or reach the upper shrub layer and canopy. Avoid cutting old growth and high quality examples. In areas that are under active forestry, where possible encourage uneven-age methods and extended rotations.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by maintaining connectivity with nearby forest patches via the retention of undisturbed natural corridors, preferably supporting forested habitats. Any development should be concentrated on forest edges, avoiding the extension of roads and road corridors into the forest. If roads must be built, minimize the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Inventory any remaining large and/or old-growth examples. Continue searching for large sites in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the composition of Allegheny oak forests in glaciated and unglaciated settings in order to characterize variations. Assess impact of spongy moths on Allegheny oak forests.

Rare Species

- Blera pictipes (Painted Wood Fly) (guide)

- Calamagrostis porteri ssp. porteri (Porter's Reed Grass) (guide)

- Carex nigromarginata (Black-edged Sedge) (guide)

- Chamaelirium luteum (Fairywand) (guide)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Bald Eagle) (guide)

- Lasiurus borealis (Eastern Red Bat) (guide)

- Lasiurus cinereus (Hoary Bat) (guide)

- Myotis lucifugus (Little Brown Bat) (guide)

- Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) (guide)

- Perimyotis subflavus (Tri-colored Bat) (guide)

- Setophaga cerulea (Cerulean Warbler) (guide)

Range

New York State Distribution

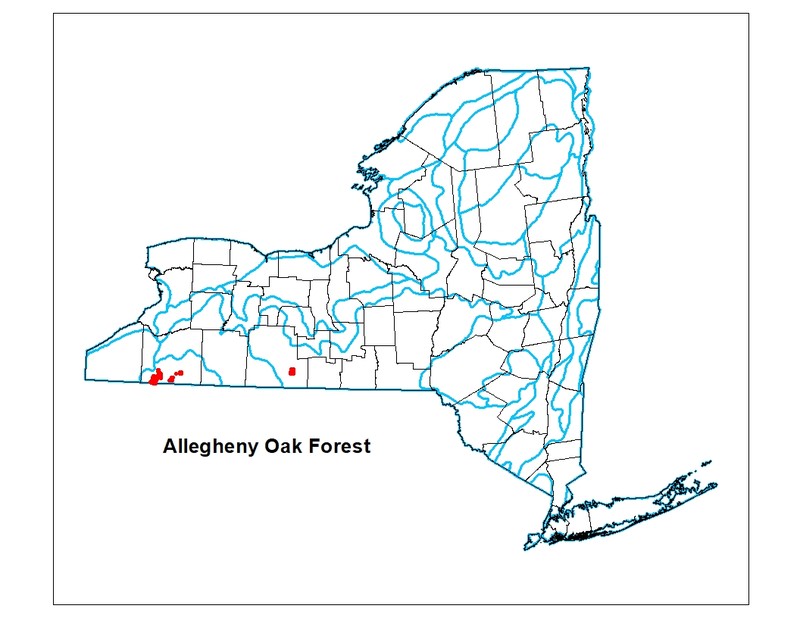

In New York, Allegheny oak forests are concentrated in the unglaciated portion of the High Appalachian Plateau in Cattaraugus and Allegany counties but also occurs in Steuben county. New York is at the northern extreme of its range which extends south within the Appalachian region to approximately North Carolina and Tennessee.

Global Distribution

Allegheny oak forest occurs on the High Allegheny Plateau of New York and Pennsylvania, the Western Allegheny Plateau of Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio, extending south to the central Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia and Maryland.

Best Places to See

- Allegany State Park

Identification Comments

General Description

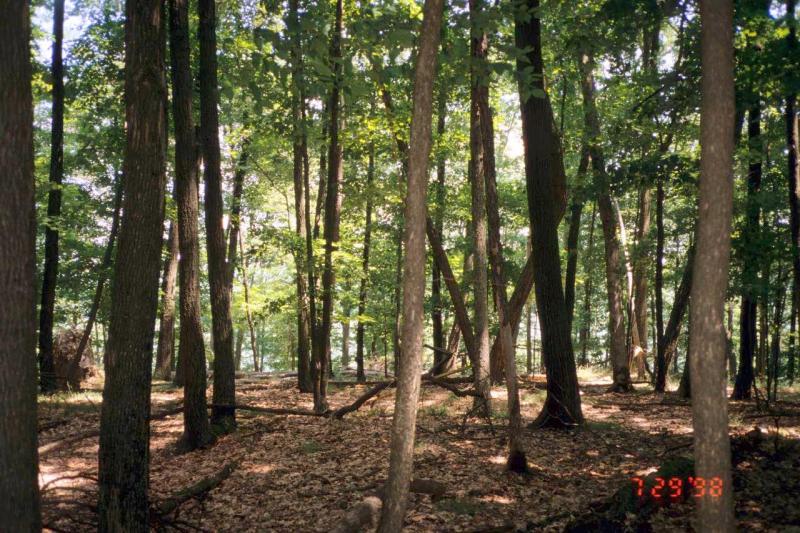

Allegheny oak forests are a narrowly defined hardwood forest community distinguished by a more diverse canopy and a richer ground flora than other mid to high elevation oak forest communities. In New York, these mixed oak forests are concentrated in the unglaciated portions of the Allegheny Plateau, where they are characteristic of well-drained rounded ridgetops and upper southeast to southwest-facing slopes with elevations between approximately 1300 to 2300 feet above sea-level. Scattered examples also occur on high elevation, glaciated areas in the Allegheny Plateau.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Allegheny oak forests are dominated by some combination of oaks including white (Quercus alba), red (Q. rubra), chestnut (Q. montana), and black (Q. velutina) often in conjunction with red maple (Acer rubrum). American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was a significant canopy associate prior to the chestnut blight and chestnut sprouts are still very common in the understory. A sapling layer is often present and the most frequent species are American chestnut, downy serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea), musclewood (Carpinus caroliniana), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), red and sugar maple (A. rubrum and A. saccharum). The tall shrub layer of American witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) is often present but relatively sparse. The low shrub layer is typically a well developed collection of mixed heath species including blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium, V. pallidum) and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), along with maple-leaved viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium). The groundlayer of herbs is typically sparse; the most characteristic species are bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), starflower (Trientalis borealis), white clintonia (Clintonia umbellulata) rough-leaved rice-grass (Oryzopsis asperifolia), black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa), and rattlesnake weed (Hieracium venosum).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 1,300 feet and 2,300 feet.

Best Time to See

During July, two species of lowbush blueberry in the understory of this community bear fruit. In autumn, the foliage of the hardwood canopy species and the understory shrubs turn rich colors providing attractive scenery.

Allegheny Oak Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- (Black Oak, White Oak) / Blue Ridge Blueberry / Western Brackenfern Allegheny Plateau-Northeast Forest (CEGL006018)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Central Appalachian Dry Oak-Pine Forest (CES202.591)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Hamamelis virginiana (witch-hazel)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Hamamelis virginiana (witch-hazel)

- Kalmia latifolia (mountain laurel)

- Rhododendron periclymenoides (pinxter-flower)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

- Viburnum acerifolium (maple-leaved viburnum)

-

Tree saplings

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Amelanchier arborea (downy shadbush)

- Carpinus caroliniana ssp. virginiana (musclewood, ironwood, American hornbeam)

- Castanea dentata (American chestnut)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

-

Tree seedlings

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

-

Herbs

- Actaea racemosa (black cohosh, black snakeroot, bug-bane)

- Aralia nudicaulis (wild sarsaparilla)

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Clintonia umbellulata (white clintonia, sPeckled wood-lily)

- Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen, teaberry)

- Geum fragarioides (barren-strawberry)

- Hieracium venosum (rattlesnake hawkweed)

- Lysimachia borealis (starflower)

- Oryzopsis asperifolia (spreading white grass)

- Polygaloides paucifolia (gay-wings, fringed milkwort)

- Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum (eastern bracken fern)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Leucobryum glaucum

- Polytrichum juniperinum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Appalachian oak-hickory forest

(guide)

Appalachain oak-hickory forest can be distinguished through its dominance by one or more of the following oaks: red oak (Quercus rubra), white oak (Q. alba), and black oak (Q. velutina) in combination with hickories (Carya spp.).

- Chestnut oak forest

(guide)

Chestnut oak forest can be distinguished via its heath understory in combination with dominance by chestnut oak or codominance of chestnut oak and typically red maple.

- Rich mesophytic forest

(guide)

Rich mesophytic forest can be distinguished by its more diverse tree composition accompanying lack of codominance of three to four oak species, the absence of both chestnut oak and a low shrub layer dominated by heaths.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Allegheny Oak Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Eaton, S.W. and E.F. Schrot. 1987. A flora of the vascular plants of Cattaraugus County, New York. Bull. Buffalo Society Natural Sci. 31: 1-235.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Gordon, R.B. 1937. The primeval forest types of southwestern New York. New York State Museum Bull. No. 321, Albany, NY.

Liebold, S. 2003. Gypsy Moth in North America. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Morgantown, WV.

McManus, M, N. Schneebergerm R. Reardon, and G. Mason. 1980. Gypsy Moth. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 162. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 14, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Allegheny oak forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/allegheny-oak-forest/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.