Appalachian Oak-Hickory Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S4

Apparently Secure in New York - Uncommon in New York but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of the state; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4G5

Apparently or Demonstrably Secure globally - Uncommon to common in the world, but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G4 or G5.

Summary

Did you know?

The New York Natural Heritage Program considers Appalachian oak-hickory forests "matrix forests." Matrix forests blanket large regions of the state and include patches of other natural communities. If the High Allegheny Plateau along the New York-Pennsylvania line were thought of as a giant chocolate chip cookie, then Appalachian oak-hickory forests would be the cookie dough and the chips would be the other embedded communities such as lakes, bogs, and swamps.

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and many are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has statewide distribution and includes several very large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of Appalachian oak-hickory forests in New York has probably declined moderately in recent decades as a result of logging, agriculture, and other development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of Appalachian oak-hickory forests in New York has probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with past logging, agriculture, and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to forests in general include changes in land use (e.g., clearing for development), forest fragmentation (e.g., roads), and invasive species (e.g., insects, diseases, and plants). Other threats may include over-browsing by deer, fire suppression, and air pollution (e.g., ozone and acidic deposition). When occurring as expansive forests, the largest threat to the integrity of Appalachian oak-hickory forests are activities that fragment the forest into smaller pieces. These activities, such as road building and other development, restrict the movement of species and seeds throughout the entire forest, an effect that often results in loss of those species that require larger blocks of habitat (e.g., black bear, bobcat, certain bird species). Additionally, fragmented forests provide decreased benefits to neighboring societies from services these societies often substantially depend on (e.g., clean water, mitigation of floods and droughts, pollination in agricultural fields, and pest control) (Daily et al. 1997). Appalachian oak-hickory forests are threatened by development (e.g., residential, agricultural, communication antennas), either directly within the community or in the surrounding landscape. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., roads, utility ROWs, excessive logging, mining, deer over-browsing), and recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, hiking trails, campgounds, ski slopes). A few Appalachian oak-hickory forests are threatened by invasive species, such as buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), bluegrass (Poa compressa), barberry (Berberis thunbergii), shrubby honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii), tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). Intentionally planted pine species (e.g., Pinus resinosa, P. strobus) may become established and be a threat to a few examples. Appalachian oak-hickory forests may be threatened by the non-native spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) which is one of North America's most devastating forest pests. The spongy moth is known to feed on the foliage of hundreds of species of plants in North America but its most common hosts are oaks and aspen. Spongy moth populations are typically eruptive in North America; in any forest stand densities may fluctuate from near 1 egg mass per ha to over 1,000 per ha. When densities reach very high levels, trees may become completely defoliated. Several successive years of defoliation, along with contributions by other biotic and abiotic stress factors, may ultimately result in tree mortality (McManus et al. 1980, Liebhold 2003).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. Avoid cutting old growth examples and encourage selective logging areas that are under active forestry.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those developments built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Inventory any remaining large and/or old-growth examples across the state. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Regularly assess the presence and degree of impact that spongy moths have on this community. Research the composition of Appalachian oak-hickory forests statewide in order to characterize variations. Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct Appalachian oak-hickory forest types based on composition and by ecoregion.

Rare Species

- Agrimonia rostellata (Woodland Agrimony) (guide)

- Allium cernuum var. cernuum (Nodding Wild Onion) (guide)

- Andersonglossum virginianum (Southern Wild Comfrey) (guide)

- Aplectrum hyemale (Puttyroot) (guide)

- Blera pictipes (Painted Wood Fly) (guide)

- Borodinia missouriensis (Green Rock Cress) (guide)

- Calamagrostis perplexa (Clausen's Reed Grass) (guide)

- Calamagrostis porteri ssp. porteri (Porter's Reed Grass) (guide)

- Carex amphibola (Ambiguous Sedge) (guide)

- Carex backii (Back's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex caroliniana (Carolina Sedge) (guide)

- Carex formosa (Handsome Sedge) (guide)

- Carex glaucodea (Glaucous Sedge) (guide)

- Carex jamesii (James' Sedge) (guide)

- Carex nigromarginata (Black-edged Sedge) (guide)

- Carex polymorpha (Variable Sedge) (guide)

- Carex retroflexa (Reflexed Sedge) (guide)

- Carex reznicekii (Reznicek's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex striatula (Lined Sedge) (guide)

- Carphophis amoenus (Eastern Wormsnake) (guide)

- Celastrina neglectamajor (Appalachian Azure) (guide)

- Citheronia regalis (Regal Moth) (guide)

- Criorhina nigriventris (Bare-cheeked Bumblefly) (guide)

- Crotalus horridus (Timber Rattlesnake) (guide)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding's Turtle) (guide)

- Endodeca serpentaria (Virginia Snakeroot) (guide)

- Frasera caroliniensis (Green Gentian) (guide)

- Geothlypis formosa (Kentucky Warbler) (guide)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Bald Eagle) (guide)

- Lactuca floridana (Woodland Lettuce) (guide)

- Lasiurus borealis (Eastern Red Bat) (guide)

- Lasiurus cinereus (Hoary Bat) (guide)

- Melanerpes erythrocephalus (Red-headed Woodpecker) (guide)

- Myotis leibii (Eastern Small-footed Myotis) (guide)

- Myotis lucifugus (Little Brown Bat) (guide)

- Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) (guide)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) (guide)

- Neotoma magister (Allegheny Woodrat) (guide)

- Oxalis violacea (Violet Wood Sorrel) (guide)

- Parrhasius m-album (White-m Hairstreak) (guide)

- Perimyotis subflavus (Tri-colored Bat) (guide)

- Platanthera hookeri (Hooker's Orchid) (guide)

- Polygonum douglasii (Douglas' Knotweed) (guide)

- Pseudotriton ruber (Red Salamander) (guide)

- Pycnanthemum clinopodioides (Basil Mountain Mint) (guide)

- Pycnanthemum torreyi (Torrey's Mountain Mint) (guide)

- Ranunculus micranthus (Small-flowered Buttercup) (guide)

- Satyrium favonius ontario (Northern Oak Hairstreak) (guide)

- Sceloporus undulatus (Fence Lizard) (guide)

- Setophaga cerulea (Cerulean Warbler) (guide)

- Silene caroliniana ssp. pensylvanica (Wild Pink) (guide)

- Tachopteryx thoreyi (Gray Petaltail) (guide)

- Triphora trianthophora (Nodding Pogonia) (guide)

- Ulmus thomasii (Rock Elm) (guide)

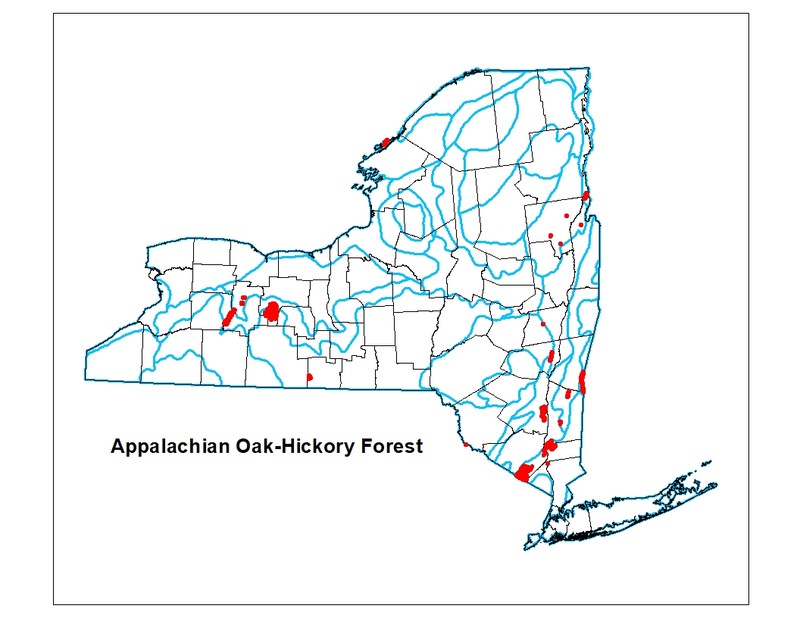

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is currently known from the lower Hudson Valley within the Hudson Highlands, the Hudson Limestone Valley, and the Taconic Foothills. Appalachian oak-hickory forests are also known from the Catskill Mountains, the St. Lawrence and southern Lake Champlain Valleys, the Lake George Valley, the Upper Delaware River Valley, and the western Finger Lakes Region.

Global Distribution

The range as a broadly-defined floristic community may be most of the Appalachian Mountains from Maine, south to Alabama and Georgia. Range of occurrences with closest floristic affinities to New York may extend north to Maine, south toTennessee and west to Ohio and Kentucky.

Best Places to See

- Harriet Hollister Spencer State Park (Livingston, Ontario Counties)

- Taconic State Park

- Appalachian National Scenic Trail, Sterling Forest State Park (Orange County)

- Western Finger Lakes Preserve (Livingston, Ontario, Steuben, Yates Counties)

- James Baird State Park

- Wellesley Island State Park (Jefferson County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A hardwood forest that occurs on well-drained sites, usually on ridgetops, upper slopes, or south- and west-facing slopes. The soils are usually loams or sandy loams. This is a broadly defined forest community with several variants. The dominant trees include one or more species of oak.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This forest invariably has a mixture of tree oaks (red, white, black) and hickories (pignut, shagbark, sweet pignut). Also, maple-leaf viburnum is commonly found in the understory.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 112 feet and 2,280 feet.

Best Time to See

Early spring is a good time to catch many of the understory trees and shrubs in bloom. Flowering dogwood, shadbush, choke cherry, and maple-leaf viburnum all provide visual sprays of color in the spring.

Appalachian Oak-Hickory Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Sugar Maple - Northern Red Oak / Round-lobe Liverleaf Forest (CEGL006046)

- (White Oak, Northern Red Oak, Black Oak) / Hickory species / Mapleleaf Viburnum Forest (CEGL006336)

- Northern Red Oak - (Pignut Hickory, Shagbark Hickory) / Hophornbeam / Blue Ridge Sedge Forest (CEGL006301)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Central Appalachian Dry Oak-Pine Forest (CES202.591)

- Northeastern Interior Dry-Mesic Oak Forest (CES202.592)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Amelanchier arborea (downy shadbush)

- Carya cordiformis (bitternut hickory)

- Carya glabra (pignut hickory)

- Carya ovata var. ovata (shagbark hickory)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Cornus florida (flowering dogwood)

- Hamamelis virginiana (witch-hazel)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Cornus racemosa (gray dogwood, red-panicled dogwood)

- Corylus cornuta ssp. cornuta (beaked hazelnut)

- Lindera benzoin (spicebush)

- Rhododendron periclymenoides (pinxter-flower)

- Rhus aromatica var. aromatica (fragrant sumac)

- Rubus idaeus ssp. strigosus (American red raspberry)

- Rubus pubescens (dwarf raspberry)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

- Vaccinium stamineum (deerberry)

- Viburnum acerifolium (maple-leaved viburnum)

- Viburnum dentatum var. lucidum (smooth arrowwood)

- Viburnum rafinesqueanum (downy arrowwood)

-

Herbs

- Actaea pachypoda (white baneberry, doll's-eyes)

- Actaea racemosa (black cohosh, black snakeroot, bug-bane)

- Aralia nudicaulis (wild sarsaparilla)

- Carex albicans (white-tinged sedge)

- Carex blanda (eastern woodland sedge)

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Carex radiata (narrow-leaved upland star sedge)

- Circaea canadensis (eastern enchanter's-nightshade)

- Desmodium paniculatum (panicled tick-trefoil)

- Galium triflorum (sweet-scented bed-straw)

- Geranium robertianum (herb-Robert)

- Geum canadense (white avens)

- Hepatica americana (round-lobed hepatica)

- Hylodesmum glutinosum (pointed-leaved tick-trefoil)

- Lysimachia quadrifolia (whorled-loosestrife)

- Maianthemum racemosum ssp. racemosum (false Solomon's-seal)

- Mitchella repens (partridge-berry)

- Nabalus albus (white rattlesnake-root)

- Podophyllum peltatum (may-apple)

- Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum (eastern bracken fern)

- Ranunculus abortivus (kidney-leaved butter-cup, kidney-leaved crow-foot)

- Solidago bicolor (silver-rod)

- Solidago caesia var. caesia (blue-stemmed goldenrod, wreath goldenrod)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Allegheny oak forest

(guide)

The Allegheny oak forest tends to have a more diverse tree canopy layer and ground flora than the Appalachian oak-hickory forests. In New York, the Allegheny oak forest is restricted to the unglaciated portions of the Allegheny plateau.

- Appalachian oak-pine forest

(guide)

Appalachian oak-pine forests are characterized by the presence of white pine or pitch pine, while Appalachian oak-hickory forests tend not to have pines and tend to have more hickories.

- Beech-maple mesic forest

(guide)

Beech-maple mesic forests tend to have fewer oaks and hickories and more sugar maple, beech, yellow birch, and white ash than Appalachian oak-hickory forests.

- Chestnut oak forest

(guide)

Chestnut oak forests tend to have a higher abundance of chestnut oak in the tree (overstory) layer as well as more black huckleberry, mountain laurel, and blueberry in the shrub layers.

- Coastal oak-hickory forest

(guide)

The coastal oak-hickory forest occurs only on the Atlantic coastal plain while the Appalachian oak-hickory forest occurs more inland.

- Oak-tulip tree forest

(guide)

Oak-tulip tree forests tend to have tulip tree, beech, and black birch in addition to oaks, while Appalachian oak-hickory forest will tend not to have these species, but will have some hickories.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Appalachian Oak-Hickory Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Daily, G.C., S. Alexander, P.R. Ehrlich, L. Goulder, J. Lubchenco, P. Matson, H.A. Mooney, S. Postel, S.H. Schneider, D. Tilman, and G.M. Woodwell. 1997. Ecosystem Services: benefits supplied to human societies by natural ecosystems. Issues In Ecology 2:1-16.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Hagan, J.M. and A.A. Whitman. 2004. Late-successional Forest:A disappearing age class and implications for biodiversity. Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences. 4 pp.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Liebold, S. 2003. Gypsy Moth in North America. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Morgantown, WV.

McIntosh, R.P. 1972. Forests of the Catskill Mountains, New York. Ecol. Monogr. 42:143-161.

McManus, M, N. Schneebergerm R. Reardon, and G. Mason. 1980. Gypsy Moth. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 162. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Ross, P. 1958. Microclimatic and vegetational studies in a cold-wet deciduous forest. Black Rock Forest Papers No. 24, Harvard Black Rock Forest, Cornwall-on-the-Hudson, New York.

The President's Council on Sustainable Development. 1999. Towards a Sustainable America: Advancing Prosperity, Opportunity, and a Healthy environment for the 21st Century. Washington, DC. 97 pp. plus appendices.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 14, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Appalachian oak-hickory forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/appalachian-oak-hickory-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.