Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Eastern white pine is a long-lived tree commonly reaching 200 years if undisturbed; maximum age may exceed 450 years. It has a remarkable rate of growth compared to other pine and hardwood species within its range. White pine also has the distinction of being the tallest tree in eastern North America. In natural pre-colonial stands it is reported to have grown to as tall as 70 meters (230 ft) tall, at least on rare occasions; the current tallest individuals reach to between 50 and 55 meters (160-180 ft).

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 500 to 4,000 occurrences statewide. A few documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is widespread throughout upstate New York and includes several very large, high quality, old-growth examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurences on public land and private conservation land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to intensive logging and development pressure.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of pine-northern hardwood forests in New York have declined moderately in recent decades as a result of intensive logging, agriculture, and other development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of pine-northern hardwood forests in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with past logging, agiculture, and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to forests in general include changes in land use (e.g., clearing for development), forest fragmentation (e.g., roads, excessive logging), recreational overuse (e.g., snowmobile trails, hiking trails), and invasive species (e.g., insects, diseases, and plants). Other threats may include over-browsing by deer, fire suppression, and air pollution (e.g., ozone and acidic deposition). Examples of this community that occur at higher elevations (e.g., >3,000 feet) may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of atmospheric deposition and climate change, especially acid rain and temperature increase.When occurring as expansive forests, the largest threat to the integrity of pine-northern hardwood forests are activities that fragment the forest into smaller pieces. These activities, such as road building and other development, restrict the movement of species and seeds throughout the entire forest, an effect that often results in loss of those species that require larger blocks of habitat (e.g., black bear, bobcat, certain birds). Additionally, fragmented forests provide decreased benefits to neighboring societies of services these societies often substantially depend on (e.g., clean water, mitigation of floods and droughts, pollination in agricultural fields, and pest control) (Daily et al. 1997). White pine blister rust may be considered a threat to occurrences of pine-northern hardwood forest that experience extreme outbreaks, especially if it coincides with other stresses and reduces white pine regeneration. White pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola) is highly virulent throughout the range of white pine. Trees are susceptible from the seedling stage through maturity. Blister rust can cause high losses both in regeneration and in immature timber stands (Wilson et al. 1965). Southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis) is a bark beetle that infests pine trees, such as pitch pine, white pine, and red pine. Southern pine beetle is native to the southeastern United States, but its range has spread up the east coast to Long Island, New York in 2014. Natural communities dominated or co-dominated by pines would likely be most impacted by southern pine beetle invasion.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine & French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees when required to do so. Avoid cutting old growth examples and encourage selective logging areas that are under active forestry.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those developments built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Inventory any remaining large and/or old-growth examples across the state. Continue searching for large sites in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the composition of pine-northern hardwood forests statewide in order to characterize variations (e.g., coastal plain and northern types). Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct pine-northern hardwood forest types based on composition and by ecoregion (e.g., red pine dominant vs. white pine dominant). More data are needed in order to clearly separate this community from Appalachian oak-pine forests and successional northern hardwoods dominated by white pine.

Rare Species

- Carex houghtoniana (Houghton's Sedge) (guide)

- Diphasiastrum complanatum (Northern Ground Cedar) (guide)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Bald Eagle) (guide)

- Lasionycteris noctivagans (Silver-haired Bat) (guide)

- Myotis lucifugus (Little Brown Bat) (guide)

- Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) (guide)

- Platanthera hookeri (Hooker's Orchid) (guide)

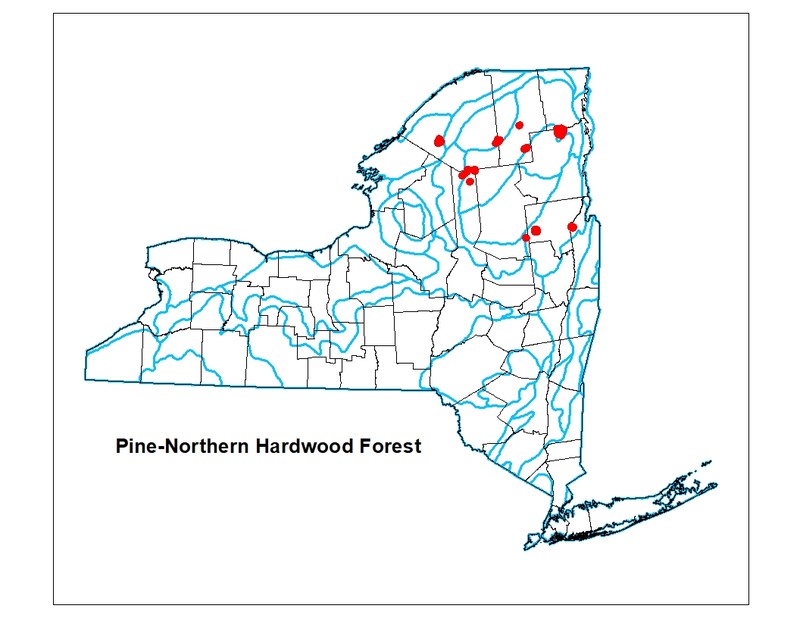

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is widespread throughout upstate New York, north of the North Atlantic Coast Ecoregion. It is more common to the north, especially in the Northern Appalachians Ecoregion where it is represented by small to large patch occurrences. Examples dominated by red pine with abundant red oak are concentrated on lake outwash plains in northeastern Essex and southeastern Clinton Counties where it approaches matrix forest size.

Global Distribution

This community is limited to the northern fringe of the Eastern United States and southern Canada. This range is estimated to span north to southern Ontario and Quebec, west to Minnesota, south to northern Michigan and northern New York, and east to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland

Best Places to See

- Five Ponds Wilderness (Herkimer, St. Lawrence Counties)

- Wilmington Wild Forest

- Adirondack Park (St. Lawrence County)

- Lake George Wild Forest (Washington County)

- Wilcox Lake Wild Forest (Hamilton, Warren Counties)

- Independence River Wild Forest (Herkimer County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Pine-northern hardwood forest occurs on gravelly outwash plains, delta sands, eskers, and dry lake sands in the Adirondacks. Generally, the combined cover of indicator species such as white pine (Pinus strobus) and red pine ( P. resinosa) in the woody layers must be at least 20% and ideally at least 50%, otherwise the occurrence may grade into other forest types such as hemlock-northern hardwood forest or beech-maple mesic forest. Physiognomy ranges from a semi-broadleaf deciduous (75% cover of hardwoods, 25% cover of conifers) to needleleaf evergreen forest.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Pine-northern hardwood forests in New York are often characterized by an emergent canopy of white pines (Pinus strobus) that overtop a mixed forest of white and/or red pine (Pinus resinosa) with northern hardwood species such as red maple (Acer rubrum), red oak (Quercus rubra), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), and yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis). Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium, V. myrtilloides) are characteristic shrubs, bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) is a common herb, and mosses and lichens may be common to abundant. Characteristic animals include pine warbler (Dendroica pinus) in mature, well-spaced pines and pileated woodpecker (Drycopus pileatus).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 360 feet and 2,225 feet.

Best Time to See

Several wildflower species of pine-northern hardwood forests can be observed in bloom throughout the spring and summer. During the early spring, flowers of miterwort (Mitella diphylla) appear on the forest floor, followed by wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), and goldthread (Coptis trifolia).

Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Sugar Maple - Eastern White Pine / Striped Maple Forest (CEGL005005)

- Jack Pine / Blueberry species / Schreber's Big Red-stem Moss Woodland (CEGL002441)

- Eastern White Pine - Red Pine / Bunchberry Dogwood Forest (CEGL006253)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Appalachian (Hemlock)-Northern Hardwood Forest (CES202.593)

- Laurentian-Acadian Northern Pine-(Oak) Forest (CES201.719)

- Laurentian-Acadian Pine-Hemlock-Hardwood Forest (CES201.563)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer pensylvanicum (striped maple)

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Betula papyrifera (paper birch)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

- Picea rubens (red spruce)

- Pinus resinosa (red pine)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium myrtilloides (velvet-leaved blueberry)

-

Tree saplings

- Abies balsamea (balsam fir)

- Acer pensylvanicum (striped maple)

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Amelanchier arborea (downy shadbush)

- Pinus resinosa (red pine)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

-

Herbs

- Aralia nudicaulis (wild sarsaparilla)

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Cornus canadensis (bunchberry)

- Dryopteris intermedia (evergreen wood fern, fancy wood fern, common wood fern)

- Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen, teaberry)

- Hypericum virginicum (Virginia marsh St. John's-wort)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Mitchella repens (partridge-berry)

- Orthilia secunda (one-sided-wintergreen)

- Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum (eastern bracken fern)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Dicranum montanum

- Hypnum imponens

- Pleurozium schreberi

- Polytrichum ohioense

Similar Ecological Communities

- Appalachian oak-pine forest

(guide)

Appalachian oak-pine forests are located in the Lower New England ecoregion and are dominated by Central Appalachian species such as white oak (Quercus alba), chestnut oak (Quercus montana), black oak (Quercus velutina), scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), and hickories (Carya spp.). Pine-northern hardwood forests are located in the Northern Appalachians and are characterized by the presence and/or dominance of white pine (Pinus strobus), red pine (Pinus resinosa), spruce (Picea spp.), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

- Beech-maple mesic forest

(guide)

Beech-maple mesic forests are characterized by co-dominance of American beech (Fagus grandifolia) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum). The combined cover of those species in pine-northern hardwood forests is generally less than 50%.

- Hemlock-northern hardwood forest

(guide)

Hemlock-northern hardwood forests tend to be found in moister areas than pine-northern hardwood forests, which occur in drier, more well-drained soils. Pine-northern hardwood forests have more white pine (Pinus strobus) or red pine (P. resinosa) and less hemlock, a species that characterizes and dominates hemlock-northern hardwood forests.

- Red pine rocky summit

(guide)

While both communities have red pine as an important component, pine-northern hardwood forest have 60% or greater tree canopy cover (>5 m) and red pine rocky summits have tree cover 25-60% with numerous rock outcrops. Trees are often stunted and contorted in summit communities. Red pine rocky summits can grade downslope into pine-northern hardwood forest.

- Spruce-northern hardwood forest

(guide)

Spruce-northern hardwood forests have significant and dominant cover of red spruce (Picea rubens), which can be present in pine-northern hardwood forests but is much less abundant.

- Successional northern hardwoods

Successional northern hardwoods that are dominated by or with greater than 20% cover of white pine (Pinus strobus) should also have characteristic successional features including successional indicator species, young canopy trees with small dbh, evidence of recent logging or relatively recent succession from a more open cultural community, and a canopy layer with poor tree diversity and poor development of multiple strata. Pine-northern hardwood forests lack these successional indicators.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Cook, D.B., R.H. Smith, and E.L. Stone. 1952. The natural distribution of red pine in New York. Ecology 33 (4): 500–512.

Daily, G.C., S. Alexander, P.R. Ehrlich, L. Goulder, J. Lubchenco, P. Matson, H.A. Mooney, S. Postel, S.H. Schneider, D. Tilman, and G.M. Woodwell. 1997. Ecosystem Services: benefits supplied to human societies by natural ecosystems. Issues In Ecology 2:1-16.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Wilson, Robert W., and William F. McQuilkin. 1965. In Silvics of forest trees of the United States. p. 329-337. H.A. Fowells, Comp. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 271. Washington, DC.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: April 3, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Pine-northern hardwood forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/pine-northern-hardwood-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.