Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S4

Apparently Secure in New York - Uncommon in New York but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of the state; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4G5

Apparently or Demonstrably Secure globally - Uncommon to common in the world, but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G4 or G5.

Summary

Did you know?

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) was a common component in Appalachian oak-pine forests prior to the chestnut blight in the early 1900s. An introduced Asian fungus, called Cryphonectria parasitica, commonly referred to as the chestnut blight, girdled and killed chestnuts. By 1950, the once common chestnut was reduced to decomposing trunks and stumps, some of which can still be found in Appalachian oak-pine forests today. Chestnut oak, sugar maple, and red oak replaced the American chestnut after this devastating fungus.

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred to a couple thousand occurrences statewide. A few documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has a limited statewide distribution and includes a few large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of Appalachian oak-pine forests in New York have probably declined moderately in recent decades as a result of logging, agriculture, and other development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of Appalachian oak-pine forests in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with past logging, agiculture, and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to forests in general include changes in land use (e.g., clearing for development), forest fragmentation (e.g., roads), and invasive species (e.g., insects, diseases, and plants). Other threats may include over-browsing by deer, fire suppression, and air pollution (e.g., ozone and acidic deposition). When occurring in expansive forests, the largest threat to the integrity of Appalachian oak-pine forests are activities that fragment the forest into smaller pieces. These activities, such as road building and other development, restrict the movement of species and seeds throughout the entire forest, an effect that often results in loss of those species that require larger blocks of habitat (e.g., black bear, bobcat, certain bird species). Additionally, fragmented forests provide decreased benefits to neighboring societies from services these societies often substantially depend on (e.g., clean water, mitigation of floods and droughts, pollination in agricultural fields, and pest control) (Daily et al. 1997). Southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis) is a bark beetle that infests pine trees, such as pitch pine, white pine, and red pine. Southern pine beetle is native to the southeastern United States, but its range has spread up the east coast to Long Island, New York in 2014. Natural communities dominated or co-dominated by pines would likely be most impacted by southern pine beetle invasion.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. Avoid cutting old-growth examples and encourage selective logging areas that are under active forestry.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Inventory any remaining large or old-growth examples across the state. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research composition of Appalachian oak-pine forests statewide in order to characterize variations. Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct Appalachian oak-pine forest types based on composition, substrate type (e.g., rocky vs. sandy loam/loamy sand soil), and by ecoregion (e.g., survey and describe "coastal oak-white pine forest" on Long Island).

Rare Species

- Callicera erratica (Golden Pine Fly) (guide)

- Carex caroliniana (Carolina Sedge) (guide)

- Carex nigromarginata (Black-edged Sedge) (guide)

- Carex retroflexa (Reflexed Sedge) (guide)

- Carex reznicekii (Reznicek's Sedge) (guide)

- Crotalus horridus (Timber Rattlesnake) (guide)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding's Turtle) (guide)

- Frasera caroliniensis (Green Gentian) (guide)

- Hydrangea arborescens (Wild Hydrangea) (guide)

- Lasiurus borealis (Eastern Red Bat) (guide)

- Lasiurus cinereus (Hoary Bat) (guide)

- Myotis lucifugus (Little Brown Bat) (guide)

- Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) (guide)

- Perimyotis subflavus (Tri-colored Bat) (guide)

- Platanthera hookeri (Hooker's Orchid) (guide)

- Pterospora andromedea (Pine Drops) (guide)

- Tachopteryx thoreyi (Gray Petaltail) (guide)

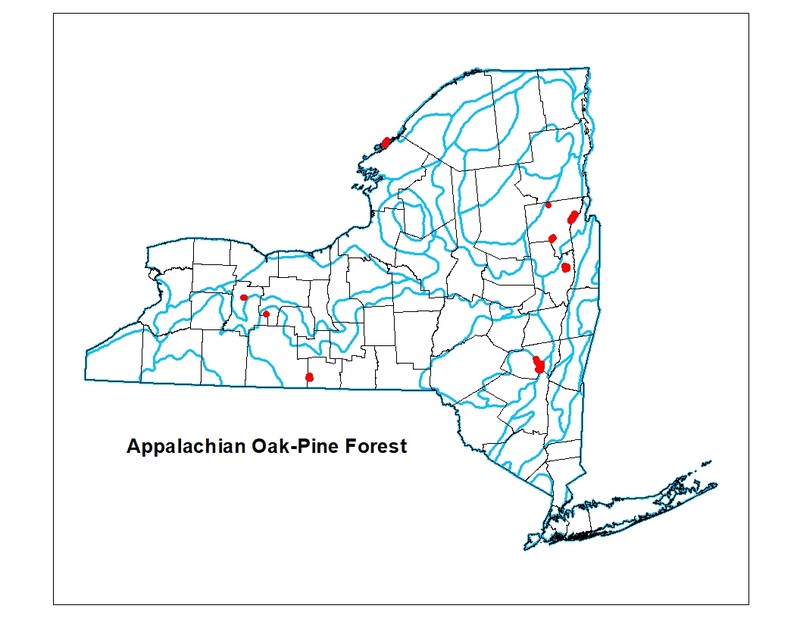

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is currently known from the Catskill Mountains, the Eastern Adirondack Low Mountains (Lake George Valley), the St., Lawrence Valley, the central High Allegheny Plateau, and the Lake Ontario Lake Plain.

Global Distribution

The range of Appalachian oak-pine forest probably spans most of the northern and central Appalachian Mountains, concentrated at the northern end of this range. This range is estimated to span northeast to upstate New York and southern Maine, west to Ohio and Kentucky, southwest to northern Georgia, and southeast to New Jersey.

Best Places to See

- Catskill Park (Greene County)

- Lake George Wild Forest, Adirondack Park (Warren County)

- Harriet Hollister Spencer State Park (Ontario County)

- Wellesley Island State Park (Jefferson County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Appalachian oak-pine forests occur on sandy or rocky soils, on slopes, ravines, or in pine barrens. The canopy is dominated by any of several oak species (Quercus alba, Q. coccinea, Q. rubra, and Q. velutina), with white pine (Pinus strobus) making up at least 25% of the total cover. On rocky slopes, the canopy abundance of pitch pine (Pinus rigida) could be greater than that of white pine at some sites. The shrub layer is dominated by ericaceous shrubs such as lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium, V. pallidum) and huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata). The herbaceous layer is usually sparse and low in species diversity.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A closed-canopy mature mixed species forest with white pine making up at least 25% of the canopy cover. The understory has a well-developed shrub layer made up of ericaceous species, and an herbaceous layer that is typically sparse.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 240 feet and 2,700 feet.

Best Time to See

During July, two species of lowbush blueberry in the understory of this community bear fruit. In autumn, the foliage of the hardwood canopy species and the understory shrubs turn bright colors and provide an attractive contrast to the dark green of the white pines present.

Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Eastern White Pine - White Oak / Inkberry Forest (CEGL006382)

- Eastern White Pine - (Northern Red Oak, Black Oak) - American Beech Forest (CEGL006293)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Appalachian (Hemlock)-Northern Hardwood Forest (CES202.593)

- Laurentian-Acadian Pine-Hemlock-Hardwood Forest (CES201.563)

- Northeastern Interior Dry-Mesic Oak Forest (CES202.592)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Betula lenta (black birch)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Hamamelis virginiana (witch-hazel)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

- Viburnum acerifolium (maple-leaved viburnum)

-

Herbs

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Danthonia spicata (poverty grass)

- Dryopteris marginalis (marginal wood fern)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Mitchella repens (partridge-berry)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Appalachian oak-hickory forest

(guide)

Appalachian oak-hickory forests have canopies that are dominated by oak species, and a percent cover of hickory species (Carya spp.) that is greater than that of white pine. In addition, the shrub and herbaceous layers may have a higher species diversity than that of Appalachian oak-pine forests.

- Chestnut oak forest

(guide)

Chestnut oak (Quercus montana) is a dominant canopy component in chestnut oak forests, and is often accompanied by other oak species (Q. alba, Q. rubra, and Q. velutina). White pine may be present, but it is not typically abundant.

- Pine-northern hardwood forest

(guide)

Like Appalachian oak-pine forests, pine-northern hardwood forests are mixed-species, closed-canopy forests with significant pine cover, but the species compositions and physical site characteristics differ between the two communities. Pine-northern hardwood forests occur on outwash plains, delta sands, or dry lake sands, and feature canopy species such as paper birch (Betula papyrifera), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), red spruce (Picea abies), and balsam fir (Abies balsamea). Pine-northern hardwood forests also have a more diverse understory and a denser herbaceous layer than Appalachian oak-pine forests.

- Pitch pine-oak forest

(guide)

Pitch pine-oak forests can have canopies dominated by oak species, but they typically include at least 25% pitch pine. This community occurs on sandy soils of glacial outwash plains or moraines, or on rocky soils of ridgetops. Scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia) can be present in the shrub layer.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

McVaugh, R. 1958. Flora of the Columbia County area, New York. Bull. 360. New York State Museum and Science Service. University of the State of New York. Albany, NY. 400 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: January 23, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Appalachian oak-pine forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/appalachian-oak-pine-forest/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.