Coastal Oak-Beech Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Beech-drops (Epifagus virginiana) is a characteristic species of coastal oak-beech forests. This parasitic plant is nearly white from lack of chlorophyll and grows only on the roots of beech trees. Instead of leaves, beech-drops have inconspicuous, ovate yellowish-purple scales. Beech-drops bloom from August to October, producing two-lipped flowers with purplish markings.

State Ranking Justification

There are an estimated 6 to 20 extant occurrences statewide. Most occurrences are on private or public conservation land, however they have questionable viability. The community is restricted to interior portions of the coastal lowlands in Suffolk and Richmond Counties and is concentrated on the north-facing slopes of moraines. The acreage, extent, and condition of coastal oak-beech forests in New York are suspected to be declining. They are vulnerable to fragmentation and extirpation by continued residential development, including golf course creation and expansion. Beech bark disease is another increasingly pervasive threat.

Short-term Trends

2023: The acreage, extent, and condition of coastal oak-beech forests in New York are suspected to be declining, primarily due to fragmentation and extirpation from residential and recreational (e.g., golf course) development, beech bark disease, beech leaf disease, heavy deer browse, and exotic species invasion.

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of coastal oak-beech forests in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in landscape connectivity.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Coastal oak-beech forests are vulnerable to fragmentation and extirpation by continued residential development, including golf course creation and expansion. Heavy deer browse and exotic species invasion are additional threats. American beech (Fagus grandifolia) trees in this community are threatened by the following diseases: 1) Beech Bark Disease causes significant mortality and defect in American beech. The disease results when bark, attacked and altered by the beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga), is invaded and killed by fungi, primarily Nectria coccinea var. faginata and sometimes N. galligena (Houston and O'Brien 1983). This disease is common across New York State (NYS DEC); 2) Beech Leaf Disease was first discovered in 2012 from northeastern Ohio (Ewing et al. 2019). The disease was first observed in New York in 2018 in Chautauqua County and was found in Suffolk and Nassau counties in 2019 (NYS DEC). It has since spread throughout western, central, and southern NY (NYS DEC). The foliar nematode Litylenchus crenatae ssp. mcannii is responsible for beech leaf disease and is believed to be non-native in North America (Carta et al. 2020, Reed et al. 2020). Beech leaf disease can kill beech trees of all ages though younger trees appear to die more quickly (NYS DEC).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

To promote a dynamic forest mosaic, allow natural processes, including gap formation from blowdowns and tree mortality as well as in-place decomposition of fallen coarse woody debris and standing snags, to operate, particularly in mature and old growth examples (Spies and Turner 1999). Management efforts should focus on the control or local eradication of invasive exotic plants and the reduction of white-tailed deer densities. Consider deer exclosures or population management, particularly if studies confirm that canopy species recruitment is being affected by heavy browse. Generally, management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine and French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that tree and shrub seedlings are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. If active forestry must occur, use silvicultural techniques and extended rotation intervals that promote regeneration of a diversity of canopy, subcanopy, and shrub species over time (Busby et al. 2009) while avoiding or minimizing both short-term and persistent residual disturbances such as soil compaction, loss of canopy cover due to logging road construction, and the unintended introduction of invasive exotic plants.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Fragmentation of coastal forests should be avoided. It is also important to maintain connectivity with adjacent natural communities not only to allow nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but to allow animals to move between them seasonally. Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/). A cross-section of coastal oak-beech forest occurrences should be protected, including the largest ones, the most mature ones, and the ones in the best landscape block. More protection of the occurrences at Friars Head and Willdwood State Park is needed.

Inventory Needs

Surveys for additional examples in Suffolk County are needed, including on private land. Leads include Gardiners Island, Lloyd Neck, Jaynes Hill, and Wading River Marsh.

Research Needs

A critical assessment of the long-term effects of heavy deer browse and beech diseases on this community, particularly addressing oak and other canopy species seedling recruitment, is needed.

Rare Species

- Andersonglossum virginianum (Southern Wild Comfrey) (guide)

- Carex nigromarginata (Black-edged Sedge) (guide)

- Crataegus uniflora (Dwarf Hawthorn) (guide)

- Gentiana saponaria (Soapwort Gentian) (guide)

- Hypericum stragulum (Low St. John's Wort) (guide)

- Lasiurus borealis (Eastern Red Bat) (guide)

- Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) (guide)

- Pinus virginiana (Virginia Pine) (guide)

Range

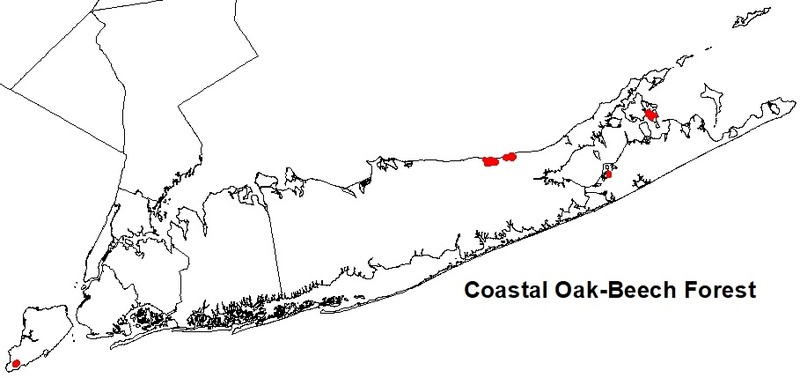

New York State Distribution

Restricted to interior portions of the coastal lowlands in Suffolk and Richmond Counties; concentrated on the north-facing slopes of moraines. Known examples range from Montauk Point (Brodo 1968) west to Big Woods along the south shore of Long Island and from Route 48 Southold to Camp Baiting Hollow along the north shore of Long Island. Numerous examples occur in the Riverhead portion of the north shore. The community is also reported from the necks of Long Island Sound (Greller 1977). It may occur in small patches farther west on Long Island to western Suffolk, Nassau and eastern Queens counties (Greller 1977). The community was also historically reported from New York City area by Harper (1917, in Brodo 1968).

Global Distribution

These forests occur along the North Atlantic Coast in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and possibly Rhode Island (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Emma Rose Elliston Park (Suffolk County)

- Wildwood State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A hardwood forest with oaks (Quercus spp.) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia) codominant that occurs in dry well-drained, loamy sand of morainal coves of the Atlantic coastal plain. Some occurrences are associated with maritime beech forest. Beech can range from nearly pure stands to as little as about 25% cover.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The forest is usually codominated by two or more species of oaks, usually black oak (Quercus velutina) and white oak (Q. alba). Scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea) and chestnut oak (Q. montana) are common associates. Red oak (Quercus rubra) may be present at low density and is a key indicator species along with sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and paper birch (Betula papyrifera). There are relatively few shrubs and herbs. Characteristic groundlayer species are Swan's sedge (Carex swanii), Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense), white wood aster (Eurybia divaricata), beech-drops (Epifagus virginiana), and false Solomon's seal (Maianthemum racemosum). Typically there is also an abundance of tree seedlings, especially of American beech; beech and oak saplings are often the most abundant "shrubs" and small trees.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 16 feet and 205 feet.

Best Time to See

During midsummer, the parasitic wildflower beech-drops, which grows on the roots of beech trees, can be observed in bloom.

Coastal Oak-Beech Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- American Beech - White Oak - Northern Red Oak Forest (CEGL006377)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dry Oak-Hardwood Forest (CES203.475)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Betula papyrifera (paper birch)

- Cornus florida (flowering dogwood)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Quercus alba (white oak)

- Quercus coccinea (scarlet oak)

- Quercus montana (chestnut oak)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Quercus velutina (black oak)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

- Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Berberis thunbergii (Japanese barberry)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

- Frangula alnus (glossy buckthorn)

- Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Prunus serotina var. serotina (wild black cherry)

- Sassafras albidum (sassafras)

- Smilax rotundifolia (common greenbrier)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (hillside blueberry)

-

Vines

- Vitis aestivalis (summer grape)

-

Herbs

- Carex swanii (Swan's sedge)

- Epifagus virginiana (beech-drops)

- Eurybia divaricata (white wood-aster)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Maianthemum racemosum ssp. racemosum (false Solomon's-seal)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Beech-maple mesic forest

(guide)

Beech-maple mesic forests occur on moister soils than coastal oak-beech forests and have a higher diversity of canopy, shrub, and herbaceous species. Beech-maple mesic forests occur throughout the state and have characteristic regional variants, whereas coastal oak-beech forests occur only on the Atlantic Coastal Plain.

- Coastal oak-heath forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-heath forest communities occur on similar substrate as coastal oak-beech communities, but the oak-heath type has a dense understory of lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium, V. pallidum) and black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), and does not have significant beech canopy cover.

- Coastal oak-hickory forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-hickory forests, like coastal oak-beech forests, occur on dry, well-drained loamy sand soils of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, but they have hickory species (Carya alba, C. glabra, or C. ovalis), rather than beech, as a canopy codominant with oaks. In addition, coastal oak-hickory forests often have a more diverse shrub and herb layer than coastal oak-beech forests.

- Coastal oak-holly forest

(guide)

Coastal oak-holly forest is codominated by black oak, black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), red maple (Acer rubrum) and American beech with abundant holly (Ilex opaca) in the subcanopy and tall shrub layers. American beech is more abundant in coastal oak-beech forest and holly is generally absent.

- Maritime beech forest

(guide)

Maritime beech forests occur on north-facing exposed bluffs and the back portions of rolling dunes in well-drained fine sands, whereas coastal oak-beech forests occur on loamy sands of morainal coves. These communities may grade into one another. Maritime beech forests, which are dominated by American beech with associated black oak and red maple (Acer rubrum), may be influenced by high winds and salt exposure due to their proximity to the ocean. Trees may have multiple stems or be stunted. Coastal oak-beech forests are not influenced by these maritime processes and have a significant presence of oak species in the tree canopy.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Coastal Oak-Beech Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Brodo, Irwin M. 1968. The lichens of Long Island, New York: A vegetational and floristic analysis. New York State Museum Bulletin 410: 1-330.

Busby, Posy E., C. D. Canham, G. Motzkin, and D. R. Foster. 2009. Forest response to chronic hurricane disturbance in coastal New England. Journal of Vegetation Science 20: 487-497.

Carta L.K, Z.A. Handoo, L. Shiguang, M. Kantor, G. Bauchan, D. McCann, C.K. Gabriel, Q. Yu, S. Reed, J. Koch, D. Martin, and D.J. Burke. 2020. Beech leaf disease symptoms caused by newly recognized nematode subspecies Litylenchus crenatae mccannii (Anguinata) described from Fagus grandifolia in North America. Forest Pathology, 50: e12580. https://doi.org/10.1111/efp.12580

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Ewing C.J., C.E. Hausman, J. Pogacnik, J. Slot, and P. Bonello. 2019. Beech leaf disease: An emerging forest epidemic. Forest Pathology 49: e12488. https://doi.org/10.1111/efp.12488

Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 140 (4):376-382.

Houston, D.R. and J. O'Brien. 1983. Beech bark disease. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 75. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reed, S.E., S. Greifenhagen, Q. Yu, A. Hoke, D.J. Burke, L.K. Carta, Z.A. Handoo, M.R. Kantor, and J. Koch. 2020. Foliar nematode, Litylenchus crenatae ssp. mccannii, population dynamics in leaves and buds of beech leaf disease-affected trees in Canada and the US. Forest Pathology, 50: e12599. https://doi.org/10.1111/efp.12599

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Rosza, R. and K. Metzler. 1982. Plant communities of Mashomack. In: The Mashomack Preserve Study. Vol. 2: Biological Resources. S. Englebright, ed. The Nature Conservancy, East Hampton, New York.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson and K. Metzler. 1996. Community alliances and elements of the eastern region. Second draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Region Conservation Science, Boston, MA. April 11. 234 pp.

Sneddon, L., M. Anderson, and J. Lundgren. 1998. International classification of ecological communities: terrestrial vegetation of the northeastern United States. July 1998 working draft. Unpublished report. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science and Natural Heritage ProgramS of the northeastern United States, Boston, MA. July 1998.

Spies, T.A. and M.G. Turner. 1999. Dynamic forest mosaics. Pages 95-160 in: M. L. Hunter, Jr., editor. Maintaining biodiversity in forest ecosystems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Taylor, Norman. 1923. The vegetation of Long Island, Part I. The vegetation of Montauk: A study of grassland and forest. Memoirs Brooklyn Botanical Garden. 2:1-107.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coastal oak-beech forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/coastal-oak-beech-forest/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.