Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Forested Mineral Soil Wetlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4G5

Apparently or Demonstrably Secure globally - Uncommon to common in the world, but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G4 or G5.

Summary

Did you know?

The hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), an exotic aphid-like insect, has become a serious threat to the eastern hemlock. These insects feed on the sap of the youngest branches of hemlock, where the needles attach to the twig. The adelgids inject a toxic saliva into the plant as they feed, killing existing needles and interfering with the tree's ability to produce new ones. If it is not controlled, the infected trees may die in three to four years. This would greatly alter the composition and function of hemlock-hardwood swamps.

State Ranking Justification

There are several thousand occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and several are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has statewide distribution, and includes a few large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include alteration of the natural hydrology and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of hemlock-hardwood swamps in New York have probably declined slightly, or have remained stable, in recent decades as a result of wetland protection regulations.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of hemlock-hardwood swamps in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with agricultural and other development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Hemlock-hardwood swamps are threatened by adjacent development (e.g., agriculture, residential, commercial, roads), habitat alteration (e.g., excessive logging, run-off), and recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, trash dumping, trails). Alteration to the natural hydrological regime is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, blocked culverts, beaver). Several hemlock-hardwood swamps are threatened by invasive species, such as reedgrass (Phragmites australis ssp. australis), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), and shrub honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.). Hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) is an exotic species that could potentially have a devastating effect on hemlock trees in New York. This exotic "sap-sucker" has only recently begun to spread through the forested areas of the northeastern United States. Without control measures, insect-infected trees will probably die within three to four years (McClure et al. 2001, Bishop 2002, Ward et al. 2004). Although current adelgid infestations are primarily confined to southeastern New York, a newly observed infestation was documented in Monroe County in 2002 (USDA Forest Service 2002).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally should not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore hemlock-hardwood swamps that have been unnaturally disturbed (e.g., remove obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology). Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities, minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of hemlock-hardwood swamp and distinguish occurrences from rich hemlock-hardwood peat swamp. A statewide review of hemlock-hardwood swamps is desirable. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the composition of hemlock-hardwood swamps statewide in order to characterize variations and clearly distinguish this community from rich hemlock-hardwood peat swamp. Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct hemlock-hardwood swamp types based on composition and by ecoregion (e.g., perhaps separately classifying swamps with a dense Rhododendron maximum tall shrub layer).

Rare Species

- Calypso bulbosa var. americana (Calypso) (guide)

- Carex arcta (Northern Clustered Sedge) (guide)

- Cypripedium arietinum (Ram's Head Lady's Slipper) (guide)

- Lygodium palmatum (Climbing Fern) (guide)

- Neottia convallarioides (Broad-lipped Twayblade) (guide)

- Petasites frigidus var. palmatus (Sweet Coltsfoot) (guide)

- Poa paludigena (Slender Marsh Blue Grass) (guide)

- Polemonium vanbruntiae (Jacob's Ladder) (guide)

- Protonotaria citrea (Prothonotary Warbler) (guide)

- Sparganium natans (Small Bur-reed) (guide)

- Triphora trianthophora (Nodding Pogonia) (guide)

- Trollius laxus (Spreading Globeflower) (guide)

Range

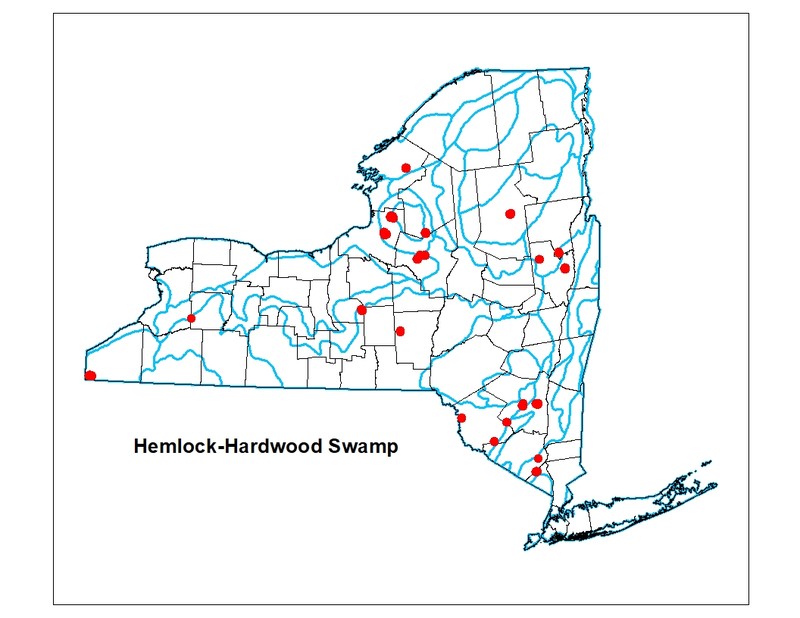

New York State Distribution

Hemlock-hardwood swamps are found throughout upstate New York, north of the coastal lowlands/north Atlantic coast, except perhaps in localized regions such as the High Peaks area of the Adirondacks. The community is apparently concentrated in the lower New England and high Alleghany regions. Large occurrences are found on the Tug Hill. Small, scattered examples occur in the rest of the northern Appalachian region and throughout the Great Lakes plain.

Global Distribution

The range of this community is probably widespread throughout much of the northeastern United States and the southern fringe of Canada. The range is estimated to span north to southern Ontario, west to Wisconsin, southwest to Kentucky and Tennessee, southeast to North Carolina and Virginia, and northeast to Nova Scotia.

Best Places to See

- Happy Valley Wildlife Management Area (Oswego County)

- West Canada Lakes Wilderness Area, Adirondack Park (Hamilton County)

- Catskill Park (Ulster County)

- Harriman State Park (Rockland County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Hemlock-hardwood swamps are closed-canopy, mixed species swamps, dominated by hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), with abundant red maple (Acer rubrum), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), and blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica). They occur on mineral soils and deep muck in depressions that receive groundwater discharge. The shrub layer is typically sparse, and features any of several shrub species, including highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), great rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum), and winterberry (Ilex verticillata). The ground layer may be sparse, and often includes cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea) and sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A closed-canopy mixed species swamp with hemlock as a dominant, located within a groundwater-fed depression. The understory is sparse, and may include highbush blueberry, great rhododendron, winterberry, and cinnamon fern.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 280 feet and 1,850 feet.

Best Time to See

During the summer, hemlock-hardwood swamps are accented with the beautiful pink flowers of great rhododendron, ripe highbush blueberries, or the spicy aroma of sweet pepperbush flowers. The hardwood and understory foliage turn brilliant colors in the fall, and provide a dramatic contrast to the dark green of the hemlock.

Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Eastern Hemlock - Yellow Birch / Common Winterberry / Peatmoss species Swamp Forest (CEGL006226)

- Eastern Hemlock / Great Laurel / Peatmoss species Swamp Forest (CEGL006279)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- North-Central Appalachian Acidic Swamp (CES202.604)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)

- Fraxinus nigra (black ash)

- Fraxinus pennsylvanica (green ash)

- Nyssa sylvatica (black-gum, sour-gum)

- Pinus strobus (white pine)

- Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock)

- Ulmus rubra (slippery elm)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Clethra alnifolia (coastal sweet-pepperbush)

- Ilex verticillata (common winterberry)

- Rhododendron maximum (great rose-bay, great laurel)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

- Viburnum lantanoides (hobblebush)

- Viburnum lentago (nannyberry)

- Viburnum nudum var. cassinoides (northern wild-raisin)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Lindera benzoin (spicebush)

-

Epiphytes

- Aralia nudicaulis (wild sarsaparilla)

-

Herbs

- Carex bromoides ssp. bromoides (brome-like sedge)

- Carex folliculata (long sedge)

- Carex trisperma (three-fruited sedge)

- Coptis trifolia (gold-thread)

- Impatiens capensis (spotted jewelweed, spotted touch-me-not)

- Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower)

- Onoclea sensibilis (sensitive fern)

- Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. cinnamomeum (cinnamon fern)

- Oxalis montana (northern wood sorrel)

- Tiarella cordifolia (foamflower)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Sphagnum spp.

Similar Ecological Communities

- Rich hemlock-hardwood peat swamp

(guide)

Rich hemlock-hardwood peat swamps have a more open canopy, a more extensive peat accumulation, and a higher understory species diversity than hemlock-hardwood swamps. Rich hemlock-hardwood peat swamps are also often fed by groundwater that flows through calcareous substrate.

- Spruce-fir swamp

(guide)

Spruce-fir swamps are basin swamps dominated by red spruce (Picea rubens), with abundant balsam fir (Abies balsamea) and red maple.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Bray, W.L. 1915. The development of the vegetation of New York State. New York State College of Forestry, Tech. Publ. No. 3, Syracuse, NY.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

McClure, M.S., S.M. Salom, and K.S. Sheilds. 2001. Hemlock wooly adelgid. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team. Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, Windsor, CT.

McVaugh, R. 1958. Flora of the Columbia County area, New York. Bull. 360. New York State Museum and Science Service. University of the State of New York. Albany, NY. 400 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Shereen Brock

Information for this guide was last updated on: February 5, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Hemlock-hardwood swamp.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/hemlock-hardwood-swamp/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.