Maritime Freshwater Interdunal Swales

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Mineral Soil Wetlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

The large cranberry (Vaccinium marcrocarpon) found in maritime freshwater interdunal swales is more commonly associated with bogs in New York. It is the same cranberry that is commerically produced for fruit and juice and is used in medical research. The plant is considered a shrub but creeps along the ground, seeming more like a small vine, and has small evergreen leaves. Commercial cranberry beds and maritime interdunal swales are both flooded seasonally, though swales are flooded more irregularly and unpredictably.

State Ranking Justification

There are approximately 20 extant occurrences statewide. The several documented occurrences are small and geographically restricted, but they have good viability and are protected on public or private conservation land. The community is restricted to the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in Suffolk County. The community's trend is declining due to threats related to invasive species, such as common reed (Phragmites australis); off-road vehicle abuse; and alterations to the natural hydrology, such as groundwater contamination, excessive groundwater withdrawls, and salt water intrusion. The surrounding landscape is vulnerable to exotic flora invasion and urban development.

Short-term Trends

Community viability/ecological integrity and area of occupancy is suspected to be slowly declining, primarily due to community conversion (from maritime freshwater interdunal swales to common reed marsh) after invasive species encroachment. Other factors in the decline include anthropogenic alterations (both physical and hydrological) to dune and swale dynamics (e.g., ATV use, beach replenishment, dune stabilization) and coastal development (e.g., groundwater contamination, filling, road construction, and community destruction).

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of maritime freshwater interdunal swales in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in hydrology, water quality, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The main threats to maritime freshwater interdunal swales include common reed (Phragmites australis) invasion, ORV abuse, and development activities. Additional threats include alterations to the natural hydrology, such as groundwater contamination, excessive groundwater withdrawls, and salt water intrusion. Deregulation of isolated wetlands, which include maritime freshwater interdunal swales, is another recent threat. In 2001, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Section 404 of the Clean Water Act did not grant the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (US ACoE) the authority to regulate the filling of isolated wetlands. This decision led U.S. Enironmental Protection Agency and US ACoE officials to issue guidance in January 2003 that made it more difficult for regulators to protect isolated wetlands (Comer et al. 2005).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Monitor the abundance of common reed (Phragmites australis) in this community and, as needed, control its encroachment. Maintain dynamic beach and dune processes, including allowing dunes to be breached and overwashed by storm events. Minimize breach closure, groundwater pollution, and road fill. Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce stormwater, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under the Freshwater Wetlands Act (Article 24 of the Environmental Conservation Law) are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

This community is best protected as part of a large beach, dune, salt marsh complex. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow dynamic ecological processes (overwash, erosion, and migration) to continue. Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities, upland beaches and dunes, and to shallow offshore communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Care should be taken to avoid groundwater contamination and to minimize hydrologic alterations during road construction. Development of site conservation plans that identify wetland threats and their sources and provide management and protection recommendations would ensure their long-term viability.

Inventory Needs

Survey and compile existing data on the Fire Island occurrences. Searches for additional occurrences and data on characteristic animals are also needed.

Research Needs

Establish predictive models of dune dynamics and groundwater hydrology to determine where additional patches of this community may arise spontaneously.

Rare Species

- Bartonia paniculata ssp. paniculata (Green Screwstem) (guide)

- Carex nigra (Black Sedge) (guide)

- Charadrius melodus (Piping Plover) (guide)

- Eupatorium pubescens (Hairy Thoroughwort) (guide)

- Helianthus angustifolius (Swamp Sunflower) (guide)

- Oxybasis rubra var. rubra (Red Pigweed) (guide)

- Platanthera cristata (Orange Crested Orchid) (guide)

- Pseudolycopodiella caroliniana (Carolina Clubmoss) (guide)

- Pycnanthemum verticillatum var. verticillatum (Whorled Mountain Mint) (guide)

- Sabatia campanulata (Slender Marsh Pink) (guide)

- Schizaea pusilla (Curlygrass Fern) (guide)

- Spiranthes vernalis (Grass-leaved Ladies' Tresses) (guide)

- Suaeda linearis (Southern Sea Blite) (guide)

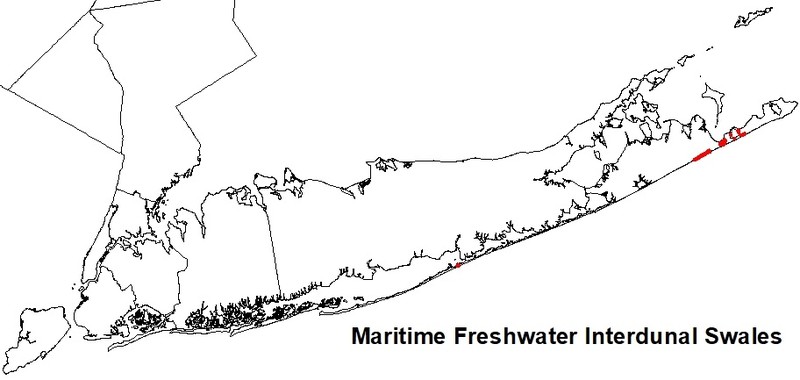

Range

New York State Distribution

Maritime freshwater interdunal swales are restricted to the Coastal Lowlands ecozone in Suffolk County. They are primarily found on the southern coasts of Long Island and Fire Island; there are smaller examples in the Peconic Bay and along the North Fork of Long Island. New York is in the central part of the range from New England south to at least New Jersey.

Global Distribution

This community is confined to major dune systems of the northeastern coast (over an estimated 350 square km). Most occurrences are found in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey, with occasional occurrences in Rhode Island and Delaware. There is one degraded occurrence in New Hampshire. There are no known occurrences in Connecticut (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Napeague Dunes (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A mosaic of wetlands that occur in low areas between dunes along the Atlantic coast; the low areas or swales are formed either by blowouts in the dunes that lower the soil surface to groundwater level, or by the seaward extension of dune fields. Soils are either sand or peaty sand; water levels fluctuate seasonally and annually, reflecting changes in groundwater levels. The dominant species are sedges and herbs; low shrubs are usually present, but they are never dominant. These wetlands may be quite small (less than 0.25 acre or 0.1 ha); species diversity is usually low. The composition may be quite variable between different interdunal swales.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic species with relatively high percent cover include large cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon), twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), three-square (Schoenoplectus americanus), royal fern (Osmunda regalis), and Sphagnum spp. Characteristic plants with low percent cover include Canada rush (Juncus canadensis), and marsh St. John's-wort (Triadenum virginicum), woolgrass (Scirpus cyperinus), highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), mermaid-weed (Proserpinaca pectinata), and grass-leaved goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia). Other less frequently occurring plants with variable cover include poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), black chokeberry (Photinia melanocarpa), three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), swamp rose (Rosa palustris), bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), sweet gale (M. gale), rose-mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos), bladderwort (Utricularia subulata), switch grass (Panicum virgatum), beakrushes (Rhynchospora alba, R. capitellata), hardhack (Spiraea tomentosa), cube-seeded iris (Iris prismatica), St. John's-wort (Hypericum sp.), swamp loosestrife (Lysimachia terrestris), cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea), sundews (Drosera intermedia, D. rotundifolia D. filiformis), flat sedges (Cyperus spp.), stiff yellow flax (Linum striatum), and slender yellow-eyed grass (Xyris torta). The invasion of common reed (Phragmites australis) is a serious threat to this community.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 5 feet and 15 feet.

Best Time to See

The grasses, sedges, and rushes that characterize the flora of this community bloom in mid- to late summer. Some of the showy associated species (the carnivorous sundews and bladderworts, cranberries and yellow-eyed grass) come into flower earlier, but a late-season visitor may be rewarded with a crop of ripe cranberries.

Maritime Freshwater Interdunal Swales Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Smooth Sawgrass / Cranberry - Northern Bayberry Wet Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006141)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dune and Swale (CES203.264)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Spiraea tomentosa (steeplebush)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry)

-

Vines

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Cladium mariscoides (twig-rush)

- Drosera rotundifolia (round-leaved sundew)

- Euthamia graminifolia (common flat-topped-goldenrod)

- Hypericum virginicum (Virginia marsh St. John's-wort)

- Juncus canadensis (Canada rush)

- Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis (royal fern)

- Phragmites australis (old world reed grass, old world phragmites)

- Proserpinaca pectinata (comb-leaved mermaid-weed)

- Rhynchospora capitellata (brownish beak sedge)

- Schoenoplectus americanus (chair-maker's bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus pungens var. pungens (three-square bulrush)

- Scirpus cyperinus (common wool-grass)

- Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens (marsh fern)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Sphagnum cuspidatum

Similar Ecological Communities

- Brackish interdunal swales

(guide)

Brackish interdunal swales are dominated by halophytic wetland species and are more likely to be inundated by tidewaters. Maritime freshwater interdunal swales have a stronger groundwater influence, are unlikely to be flooded by extreme tides, and are dominated by freshwater wetland species, including twig-rush, flat sedges, and beakrush.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Freshwater Interdunal Swales. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Comer, P. K. Goodin, G. Hammerson, S. Menard, M. Pyne, M.Reid, M. Robles, M. Russo, L. Sneddon, K. Sno, A. Tomaino, and M. Tuffy. 2005. Biodiversity Values of Geographically Isolated Wetlands: An Analysis of 20 U.S. States. NatureServe, Arlington, VA.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Johnson, Anne F. 1985. A guide to the plant communities of the Napeague dunes Long Island, New York. Mad Printers, Mattituck, New York. 58 pp.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime freshwater interdunal swales.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-freshwater-interdunal-swales/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.