Brackish Interdunal Swales

- System

- Estuarine

- Subsystem

- Estuarine Intertidal

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1S2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled in New York - Especially or very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either S1 or S2.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Brackish interdunal swales are known for their importance to wildlife. Characteristic fauna includes salt marsh mosquitoes, fiddler crabs, piping plovers, American oystercatchers, yellowlegs (during migration), and Canada geese, which use the community as a foraging ground. Eastern mud turtle and eastern spadefoot toad also reportedly use this habitat (United States Army Corps of Engineers 1996, 1999).

State Ranking Justification

There are relatively few small, geographically restricted occurrences of this community. Although they are protected on public or private conservation land, they are threatened by management practices that alter natural hydrologic processes (such as breach contingency plans) and invasive species, such as common reed (Phragmites australis). The surrounding landscape is vulnerable to exotic flora invasion and urban development.

Short-term Trends

Community viability/ecological integrity and area of occupancy is suspected to be slowly declining, primarily due to community conversion (from brackish interdunal swales to estuarine common reed marsh) after invasive species encroachment. Other factors in the decline include anthropogenic alterations (both physical and hydrological) to dune and swale dynamics and coastal development (e.g., filling, road construction, and community destruction).

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of brackish interdunal swales in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in hydrology, water quality, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The main threat to brackish interdunal swales is invasion by common reed (Phragmites australis), which may rapidly expand to convert this community to an estuarine common reed marsh. Breach contingency plans for public lands that include dune stabilization and repair, overwash water drainage, and other hydrologic alterations threaten processes that create and maintain the community. Additional threats include groundwater pollution and filling during road construction and development.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Monitor the abundance of common reed (Phragmites australis) in this community and, as needed, control its encroachment. Maintain dynamic beach and dune processes, including allowing dunes to be breached and overwashed by storm events. Minimize breach closure, groundwater pollution, and road fill.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

This community is best protected as part of a large beach, dune, salt marsh complex. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow dynamic ecological processes (overwash, erosion, and migration) to continue. Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities, upland beaches and dunes, and to shallow offshore communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Care should be taken to avoid groundwater contamination and to minimize hydrologic alterations during road construction. Development of site conservation plans that identify wetland threats and their sources and provide management and protection recommendations would ensure their long-term viability.

Inventory Needs

Searches for additional occurrences are needed, especially along the barrier islands of Long Island between Democrat Point and Southampton Beach. Fire Island East and Fire Island Wilderness should be surveyed first. Other leads include Democrat Point, Westhampton Beach and Montauk Point. The biota at the Jones Beach Island sites need to be more accurately mapped and characterized.

Research Needs

Establish predictive models of dune dynamics to determine where additional patches of this community may arise spontaneously. Evaluate whether the strain of common reed (Phragmites australis) that is invading brackish interdunal swales is native.

Rare Species

- Bolboschoenus maritimus ssp. paludosus (American Saltmarsh Bulrush) (guide)

- Carex hormathodes (Marsh Straw Sedge) (guide)

- Charadrius melodus (Piping Plover) (guide)

- Diplachne fusca ssp. fascicularis (Salt-meadow Grass) (guide)

- Egretta thula (Snowy Egret) (guide)

- Gelochelidon nilotica (Gull-billed Tern) (guide)

- Helianthus angustifolius (Swamp Sunflower) (guide)

- Iris prismatica (Slender Blue Flag) (guide)

- Juncus scirpoides (Sedge Rush) (guide)

- Oxybasis rubra var. rubra (Red Pigweed) (guide)

- Pycnanthemum muticum (Blunt Mountain Mint) (guide)

- Rumex fueginus (American Golden Dock) (guide)

- Rumex hastatulus (Heart Sorrel) (guide)

- Sabatia campanulata (Slender Marsh Pink) (guide)

- Sabatia stellaris (Sea Pink) (guide)

- Sterna dougallii (Roseate Tern) (guide)

- Sterna hirundo (Common Tern) (guide)

- Symphyotrichum subulatum var. subulatum (Annual Saltmarsh Aster) (guide)

Range

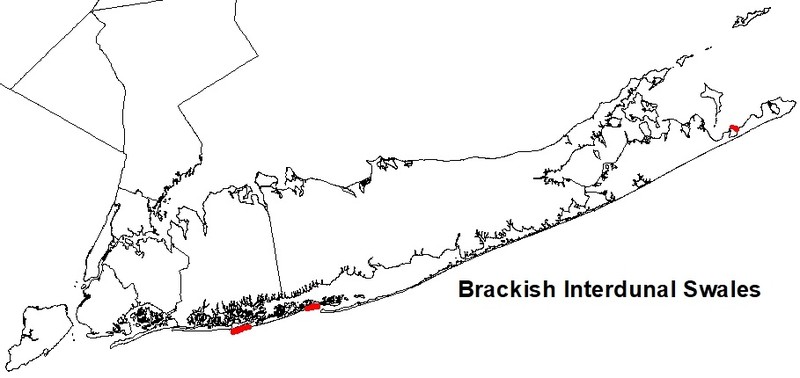

New York State Distribution

Brackish interdunal swales are restricted to estuarine portion of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone, probably only on the south shore of Long Island. Known occurrences are restricted to the barrier islands from Jones Beach Island West to Westhampton Beach. Additional occurrences are possible west to Gateway National Recreation Area and east to Montauk Point.

Global Distribution

Restricted to estuarine portions of the North Atlantic Coast, Chesapeake Bay Lowlands, and Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain Ecoregions. It is documented from Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire (NatureServe 2009). It likely occurs in other states and may range south to North Carolina and north to Maine. Occurrences south of northeastern North Carolina may be related but likely have substantial floristic differences.

Best Places to See

- Hither Hills State Park (Suffolk County)

- Gilgo State Park (Suffolk County)

- Jones Beach State Park (Nassau County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A brackish marsh community in interdunal swales that are infrequently flooded by unusually high tides. Ths community is dominated by halophytic graminoids. Individual swales occur as small patches positioned between fore-, primary, and secondary dunes in a maritime dunes system, typically on barrier islands. Swales experience dynamic fluctuations in water levels and salinity. Water levels are highest after infrequent and sporadic overwash. This occurs during spring tides, full moons, or major storms when waves overtop the highest part of the dunes. Water and suspended sand are then transported through the foredune into low-lying areas within the dune system. Flood frequency can vary from several times per year to as little as once every 25 years, forming temporary ponds. During the driest times, ponds evaporate, surface sands are no longer saturated, salt concentrates and then enters the groundwater, and salt deposits form on the surface. Salinity is typically mixohaline, with water being derived from a mix of saline ocean overwash and freshwater groundwater lens. However, salinity can vary greatly at certain times of the year from oligohaline (0 ppt) to supersaline (70 ppt) in response to the salinity of the groundwater and accumulation of salt during evaporation. Soils are deep sands that often become anaerobic but lack peat accumulation. The surface is often rusty colored from a coating of blue-green algae. Community variants include semi-permanent pools, long-lived wet swales with perennial graminoids, and newly-formed sparsely-vegetated damp swales with early successional annual forbs. Occurrences of this community are sometimes ephemeral, representing the early stages of salt marsh or coastal salt pond formation or rapidly transforming into common reed marshes. Brackish interdunal swales were previously included in coastal salt pond (Reschke 1990).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The dominant flora are mostly grasses, sedges and rushes including salt-meadowgrass (Spartina patens), dwarf spikerush (Eleocharis parvula), three-square (Schoenoplectus pungens), flatsedge (Cyperus polystachyos), and jointed rush (Juncus articulatus). The abundance of any one dominant can vary widely year to year in response to salinity fluctuations. Other characteristic flora includes halophytes such as salt-meadow grass (Diplachne maritima), seaside bulrush (Bolboschoenus maritimus ssp. paludosus), toad-rush (Juncus ambiguus), sedge-rush (Juncus scirpoides), mock bishop's-weed (Ptilimnium capillaceum), golden dock (Rumex maritimus), eastern annual saltmarsh aster (Symphyotrichum subulatum var. subulatum), red pigweed (Chenopodium rubrum), saltmarsh fleabane (Pluchea odorata), rose-mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos), knotweed (Polygonum ramosissimum), and saltmarsh-elder (Iva frutescens). Seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus) may grow at the upper edge of this community in drift lines, but is more successful on maritime beaches and dunes. Common reed (Phragmites australis) may become invasive in brackish interdunal swales.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 3 feet and 10 feet.

Best Time to See

The grasses, sedges, and rushes that characterize the flora of this community bloom in mid- to late summer. Some of the showy associated species (saltmarsh fleabane, saltmarsh aster, and rose-mallow) should also be flowering at that time, presenting a palette of pale pinks to deep purple.

Brackish Interdunal Swales Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Saltmeadow Cordgrass - Dwarf Spikerush Marsh (CEGL006342)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Dune and Swale (CES203.264)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Baccharis halimifolia (groundsel-tree)

- Iva frutescens (salt marsh-elder)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

-

Herbs

- Bolboschoenus maritimus ssp. paludosus (American salt marsh bulrush)

- Cyperus polystachyos (many-spiked flat sedge)

- Distichlis spicata (salt grass)

- Eleocharis parvula (salt-loving spike-rush)

- Euthamia caroliniana (slender flat-topped-goldenrod)

- Hibiscus moscheutos ssp. moscheutos (swamp rose-mallow)

- Hypericum mutilum ssp. mutilum (dwarf St. John's-wort)

- Juncus articulatus (jointed rush)

- Juncus canadensis (Canada rush)

- Lycopus uniflorus (northern bugleweed, northern water-horehound)

- Lycopus virginicus (Virginia bugleweed, Virginia water-horehound)

- Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife)

- Persicaria lapathifolia (dock-leaved smartweed)

- Phragmites australis (old world reed grass, old world phragmites)

- Pluchea odorata (salt marsh-fleabane)

- Polygonum ramosissimum ssp. ramosissimum (bushy knotweed)

- Ptilimnium capillaceum (mock bishopweed)

- Ruppia maritima (widgeon-grass, ditch-grass)

- Sabatia stellaris (sea-pink)

- Schoenoplectus americanus (chair-maker's bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus pungens var. pungens (three-square bulrush)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

- Spartina patens (salt-meadow cord grass)

- Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens (marsh fern)

-

Submerged aquatics

- Eleocharis parvula (salt-loving spike-rush)

Similar Ecological Communities

- High salt marsh

(guide)

High salt marsh is a coastal marsh community that occurs in a zone extending from mean high tide up to the limit of spring tides; dominants include salt-meadow grass, spikegrass, or a dwarf form (15 to 30 cm tall) of cordgrass. Brackish interdunal swales occur inland between maritime dunes and are typically more rich and diverse floristically than high salt marshes.

- Maritime freshwater interdunal swales

(guide)

Maritime freshwater interdunal swales have a stronger groundwater influence, are unlikely to be flooded by extreme tides, and are dominated by freshwater wetland species, including twig-rush, flat sedges, and beakrush. Brackish interdunal swales are dominated by halophytic wetland species and are more likely to be inundated by tidewaters.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Brackish Interdunal Swales. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

United States Army Corps of Engineers. 1996. Fire Island to Montauk Point Long Island, New York. Breach contingency plan. Unpublished report. January. 45 pp.

United States Army Corps of Engineers. 1999. Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point, Long Island, New York. Reach 1. Fire Island Inlet. Draft decision document, an evaluation of an interim plan for storm damage protection. Volume 1. Main report and draft environmental impact statement. United States Army Corps of Engineers. New York District.

Zaremba, Robert E. 1992. Field survey to Jones Beach Island East of October 28, 1992.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Brackish interdunal swales.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/brackish-interdunal-swales/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.