Coastal Plain Poor Fen

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Peatlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3?

Vulnerable globally (most likely) - Conservation status is uncertain, but most likely at moderate risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 80 or fewer populations or locations in the world, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign a firm conservation status.

Summary

Did you know?

Sedges and rushes are often found in coastal plain poor fens. Naturalists have come up with a saying to help remember the differences between these two grasslike plants: "Sedges have edges, rushes are round (and grasses have nodes from the top to the ground). Rushes (members of the Juncus Family of plants) have had many uses in human history. One origin of the word Rush is from old English or German meaning to knit. The stems of the rush plant have been used for centuries to weave chair seats and in Japan to weave the soft surface of tatami mats. The pith, or center of the rush, was also used to make a type of candle called "rushlight." It is best to try and identify individual rush species in the late summer. Don't forget to bring your hand lens!

State Ranking Justification

There are very few occurrences of this community type. A few have good viability and are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community does not have statewide distribution, occurring only on the coastal plain of Long Island. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure or alteration to the natural hydrology. This community has declined moderately to substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with population increase.

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of inland poor fens in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of wetland protection regulations. The complete, historical, acreage for this community type is unknown but was probably less than 1000 acres. The total, current, acreage for this community type is currently less than 100 acres. This decline is due primarily to alterations in hydrology caused by residential and commercial development. Alterations included draining, ditching or filling in, and an increased demand for fresh water resulting in a lower water table. Invasive species could speed up the decline of this community by out-competing the native species.

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of coastal plain poor fens in New York have probably declined moderately from historical numbers. This decline is correlated with the settlement of the area and corresponding residential, agricultural, and commercial development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to coastal plain poor fens include disruption of natural hydrology, pressure from residential and commercial development, and invasion of exotic species. Disruptions to the natural hydrology can be due to water control structures (dams, impoundments), increased use of groundwater, and storm water run-off. Residential and commercial development can not only cause a disruption to the natural hydrology as stated above but can also result in a suppression of the natural fire regime of the surrounding forested landscape which also effects this wetland. Finally, invasive species such as common reed (Phragmites australis) are making advances into these wetland systems.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Coastal plain poor fens are particularly vulnerable to changes in hydrology and water quality. Changes in hydrology include impoundment, draining, and ditching. The water quality of these fens can be impacted by nearby development and storm water run-off. In addition, management plans need to consider the impact of invasive species, such as common reed (Phragmites australis), on the natural species composition of these fens. Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food. After settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of coastal plain poor fens. Finding occurrences with several fens forming a complex should be a priority. A region wide review of these fens is desirable. In particular, some of the known locations of this community type may be intermediate between a coastal plain poor fen and other coastal wetland types. A specific inventory need is to set up permanent plots at known locations in order to gather species data at yearly intervals and at different times within the same year.

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about coastal plain poor fens, especially to advance our understanding of their classification, ecological processes (e.g., fire), hydrology, floristic variation, characteristic fauna, and fen development and succession. This research will provide the basic facts necessary to assess how human alterations in the landscape affect these fens, and supply a framework for evaluating the relative value of coastal plain poor fens. In particular, research is needed to better compare these types of fens with other similar communities on Long Island and also New York State in general. These fens should also be monitored for invasive species, disturbance and trampling (off-road vehicle use), water quality (storm water drainage) and water hydrology.

Rare Species

- Carex barrattii (Barratt's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex polymorpha (Variable Sedge) (guide)

- Carex styloflexa (Bent Sedge) (guide)

- Carex venusta (Dark-green Sedge) (guide)

- Chasmanthium laxum (Slender Spike Grass) (guide)

- Enallagma laterale (New England Bluet) (guide)

- Enallagma weewa (Blackwater Bluet) (guide)

- Gentiana saponaria (Soapwort Gentian) (guide)

- Libellula flavida (Yellow-sided Skimmer) (guide)

- Neottia bifolia (Southern Twayblade) (guide)

- Papaipema appassionata (Pitcher Plant Borer Moth) (guide)

- Papaipema stenocelis (Chain Fern Borer Moth) (guide)

- Schizaea pusilla (Curlygrass Fern) (guide)

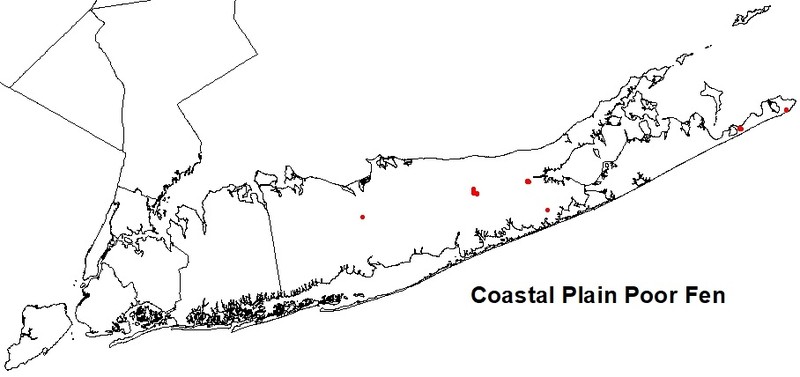

Range

New York State Distribution

The coastal plain poor fen has a narrow range in New York where it is restricted to the coastal lowlands in Suffolk County. It occurs only in a narrow band in the central part of eastern Long Island. The historical range is unknown, but was probably around the same as it is today. Total range is uncertain; New York is probably in the central part of a range extending from southern New England along the coast to New Jersey.

Global Distribution

Although probably more widespread than is currently known, the coastal plain poor fen typically occurs along the Northern Atlantic coastal plain. This community can be found on Cape Cod (Massachusetts), Long Island (New York), and the coastal plain and near-coastal areas of northern New Jersey. North of the glacial border, this natural community occurs in isolated glacial kettleholes and in similar isolated basins in New Jersey in regions of deep sands (NatureServe Explorer 2009).

Best Places to See

- Quogue Wildlife Refuge (Suffolk County)

- Otis Pike Preserve (Suffolk County)

- Peconic River SCFWH (Suffolk County)

- Hither Hills State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

Coastal plain poor fens are weakly minerotrophic peatlands that occur on the coastal plain, in which the substrate is peat composed primarily of peat mosses (Sphagnum spp.), with admixtures of graminoid and woody peat. Poor fens are fed by waters that are weakly mineralized, with low pH values, generally between 4.0 and 5.5 (Andrus 1980). On Long Island, coastal plain poor fens occur from the Nissequogue River and the central south shore to Montauk Point. They are best developed on the Roanoke Point Moraine outwash plain and the Ronkonkoma Moraine. Coastal plain poor fen appears to form best in small "delta-like" areas of organic deposits near the small stream outlets of coastal plain pond basins. Major ecological factors influencing this community include groundwater discharge combined with one or more of the following hydrological influences: coastal plain pond shore draw down, stream flow, or an abbreviated freshwater tide. Fire regime may influence poor fens situated within fire prone landscapes. Coastal plain poor fen vegetation appears to form readily behind stream impoundments.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The dominant plants are peat mosses (Sphagnum spp.), with scattered sedges, shrubs, and stunted trees. Sphagnum henryense is a characteristic peat moss; additional species include S. bartlettianum, S. fallax, S. flavicomans, S. magellanicum, S. papillosum, S. recurvum, and S. torreyanum. Characteristic shrubs include hardhack (Spiraea tomentosa), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), large cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) water-willow (Decodon verticillatus), sweet gale (Myrica gale), and dwarf huckleberry (Gaylussacia dumosa). Small patches within the fen may be dominated by dwarf shrubs and may be classified as dwarf shrub bog. Characteristic herbs include twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), sedges (Carex utriculata, C. lasiocarpa, C. striata, C. exilis), beakrushes (Rhynchospora alba, R. fusca), rushes (Juncus canadensis, J. pelocarpus), cottongrass (Eriophorum virginicum), sundews (Drosera intermedia, D. rotundifolia), marsh St. John's-wort (Triadenum virginicum), bladderworts (Utricularia striata, U. purpurea), knotted spikerush (Eleocharis equisetoides), swamp loosestrife (Lysimachia terrestris), rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides), grass pink (Calopogon tuberosus), meadow beauty (Rhexia virginica), and white water-lily (Nymphaea odorata). Sedges and rushes often overtop short shrubs by mid to late summer. Scattered stunted trees such as Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) and red maple (Acer rubrum) may also be present. Fauna observed in coastal plain poor fens include common snipe (Gallinago gallinago), great blue heron (Ardea herodias), green frog (Rana clamitans melanota), bull frog (Rana catesbeiana), and spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 5 feet and 40 feet.

Best Time to See

The best time to visit a coastal plain poor fen community would be mid to possibly late summer. This is the time when most of the herbaceous species would be in flower and the blueberries may be ripe.

Coastal Plain Poor Fen Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Sweetgale - Leatherleaf / Coastal Sedge Fen (CEGL006392)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Atlantic Coastal Plain Northern Bog (CES203.893)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Chamaecyparis thyoides (Atlantic white cedar)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

- Chamaecyparis thyoides (Atlantic white cedar)

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Cephalanthus occidentalis (buttonbush)

- Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf)

- Clethra alnifolia (coastal sweet-pepperbush)

- Decodon verticillatus (water-willow)

- Gaylussacia bigeloviana (bog huckleberry)

- Myrica gale (sweet gale)

- Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry)

-

Herbs

- Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana (slender bog sedge)

- Carex utriculata (bottle-shaped sedge)

- Cladium mariscoides (twig-rush)

- Drosera intermedia (spatulate-leaved sundew)

- Eriophorum virginicum (tawny cotton-grass)

- Rhynchospora alba (white beak sedge)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Sphagnum spp

-

Floating-leaved aquatics

- Nymphaea odorata ssp. odorata (fragrant white water-lily)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Dwarf shrub bog

(guide)

This type of wetland is very similar to the coastal plain poor fen but only occurs north of the coastal plain and is underlain by bedrock instead of sand.

- Highbush blueberry bog thicket

(guide)

The dominant shrub here is the tall highbush blueberry. In coastal plain poor fens, the shrubs are typically short with the grasses and sedges overtopping them.

- Inland poor fen

(guide)

This community occurs north of the coastal plain. It differs from coastal plain poor fen by having fewer low shrubs (typically less than 50% cover).

- Sea level fen

(guide)

This is a small patch, sedge-dominated fen community that occurs at the upper edge of salt marsh complexes just above sea level where there is adjoining freshwater seepage. These fens are fed by acidic and oligotrophic freshwater seepage which mixes with salt or brackish water from tidal overwash at infrequent intervals, reportedly only during unusually high tides.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Coastal Plain Poor Fen. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Andrus, R.E. 1980. Sphagnaceae (Peat Moss Family) of New York State. Bulletin No. 442. New York State Museum. Albany, NY.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

MacDonald, Dana and Gregory Edinger. 2000. Identification of reference wetlands on Long Island, New York. Final report prepared for the Environmental Protection Agency, Wetland Grant CD992436-01. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 106 pp. plus appendices.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated October, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Olivero, Adele M., Kathryn J. Schneider, and Troy W. Weldy. 2000. Rare species and ecological communities of Hither Hills State Park. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 74 pp. plus appendices.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Slack, Nancy G. 1994. Can one tell the mire type from the bryophytes alone? J. Hattori Bot. Lab 75:149-159.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coastal plain poor fen.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/coastal-plain-poor-fen/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.