Sea Level Fen

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Peatlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G1G2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled globally - At very high or high risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in the world, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either G1 or G2.

Summary

Did you know?

Did you know that freshwater peatlands can develop right next to a salt marsh? It can, but this type of natural community is very rare. It occupies a unique habitat where there are areas of freshwater seepage adjacent to salt marshes. Possibly, there may only be around 15 sites from Virginia to Massachusetts where this natural community occurs. Also, each of these sites only occupies a few acres at best.

State Ranking Justification

There are very few occurrences of sea level fens in New York. They are all small in size (acreage) and the trend is toward a decrease in size. Most are threatened in a vulnerable, densely-populated landscape, however, some sites are located in more protected, conservation areas.

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of sea level fens in New York have probably declined in recent decades as a result of threats from development, changes to natural hydrology, decline in water quality, and spread of invasive species.

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of sea level fens in New York have probably declined from historical numbers likely correlated with the alteration to the natural hydrology (ditching, draining, and impoundments) and decline in water quality as a result of settlement and development. Given the unique setting of having sufficient freshwater discharge at the upper margin of a salt marsh, this community was probably always rare.

Conservation and Management

Threats

The major threats to the sea level fen community are alterations to the natural hydrology from a variety of sources and the spread of invasive species. The hydrology of this natural community type has been altered for decades. Alterations have included: mosquito ditching, the dredging of channels for boat traffic, filling in of the wetland, and draw down of the water table from an increased demand for freshwater. The invasion of common reed (Phragmites australis) into these communities is also a significant threat. Other threats include non-point source pollution, pesticide use, and other construction such as roads.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management of sea level fens should include the removal and control of common reed (Phragmites australis). Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for additional occurrences, especially elsewhere in the Peconic Bay Region of Long Island and Long Island's South Shore Estuaries. Sites supporting indicator species such as spikerush (Eleocharis rostellata) and twig rush (Cladium mariscoides) should be evaluated. In addition, more surveys of both plants and animals are needed as well as plots for community documentation at known locations.

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about sea level fens, especially to advance our understanding of their classification, ecological processes, hydrology, floristic variation, characteristic fauna, and fen development and succession. This research will provide the basic facts necessary to assess how human alterations in the landscape affect these types of fens. Research is also needed to evaluate the native status of some stands of common reed (Phragmites australis ssp. americanus).

Rare Species

- Abagrotis benjamini (Coastal Heathland Cutworm) (guide)

- Apamea burgessi (Burgess's Apamea) (guide)

- Apamea inordinata (Irregular Apamea) (guide)

- Carex hormathodes (Marsh Straw Sedge) (guide)

- Derrima stellata (Pink Star Moth) (guide)

- Dichagyris acclivis (Switchgrass Dart) (guide)

- Gentiana saponaria (Soapwort Gentian) (guide)

- Iris prismatica (Slender Blue Flag) (guide)

- Juncus scirpoides (Sedge Rush) (guide)

- Lilaeopsis chinensis (Eastern Grasswort) (guide)

- Marimatha nigrofimbria (Black-bordered Lemon Moth) (guide)

- Oligia bridghamii (Bridgham's Brocade) (guide)

- Sabatia campanulata (Slender Marsh Pink) (guide)

- Symphyotrichum subulatum var. subulatum (Annual Saltmarsh Aster) (guide)

- Tripsacum dactyloides (Northern Gama Grass) (guide)

Range

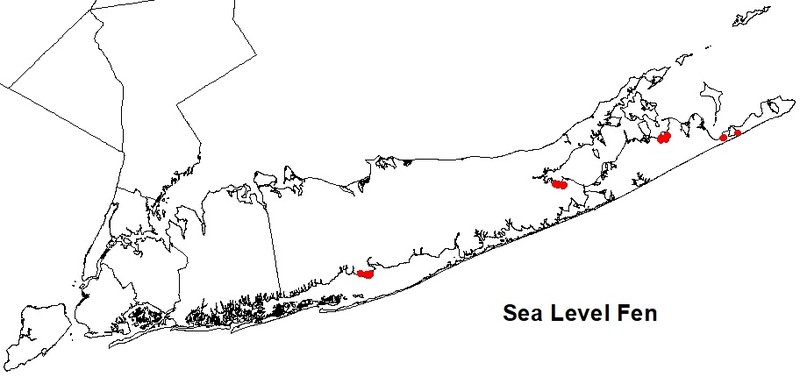

New York State Distribution

Sea level fens are restricted to the estuarine portion of the coastal lowlands. It occupies a unique habitat where there are areas of freshwater seepage adjacent to salt marshes. There are about six documented occurrences in Suffolk county. The historical range of this natural community is unknown.

Global Distribution

This community is restricted to a unique habitat along the mid and north atlantic coastal plain: areas of freshwater seepage adjacent to salt marshes. Presently, occurrences are known from Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Virginia, and Rhode Island, with possible occurrences in Maryland. This community may be more widespread but not documented (NatureServe Explorer 2009).

Best Places to See

- Northwest Creek SCFWH (Suffolk County)

- Napeague State Park (Suffolk County)

- Flanders Bay Wetlands SCFWH (Suffolk County)

- Hubbard County Parkland (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

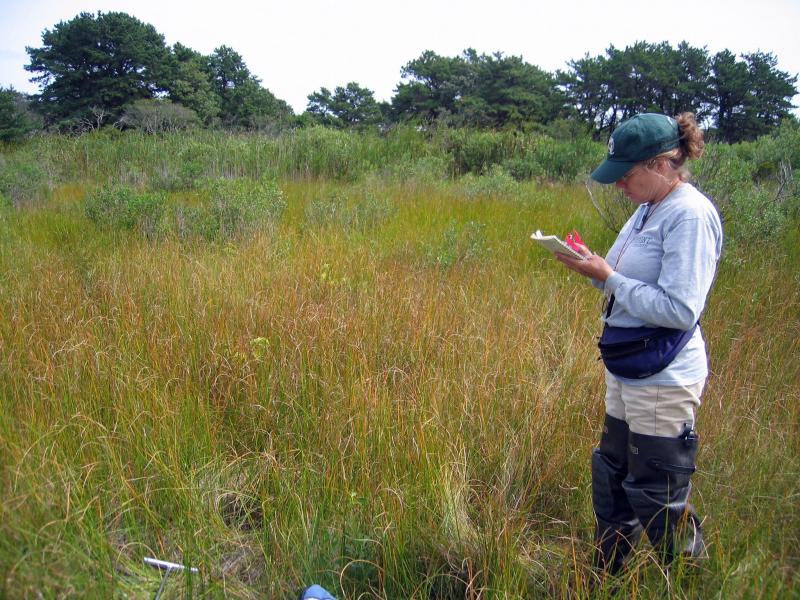

This is a small patch, sedge-dominated fen community that occurs at the upper edge of salt marsh complexes just above sea level where there is adjoining freshwater seepage. Soils are those of a peatland with deep sedgy peat underlain by deep sand or gravel. The fen is herb dominated (nearly 100% cover) but can have trees and shrubs at low percent cover. Herbaceous species include spikerush (Eleocharis rostellata), twig-rush (Cladium mariscoides), and three-square (Schoenoplectus pungens). Typical trees and shrubs include scattered individuals of red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), pitch pine (Pinus rigida), and bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A small patch, sedge-dominated fen community that occurs at the upper edge of salt marsh complexes just above sea level where there is adjoining freshwater seepage. Although its association with salt marshes is diagnostic, it is only infrequently influenced by salt or brackish overwash during unusually high tides. This natural community is dominated by herbs, occasionally with some scattered shrubs or short trees.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 1 feet and 6 feet.

Best Time to See

The best time to see this natural community is during the summer when a large diversity of plants and animals can be found.

Sea Level Fen Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Smooth Sawgrass - Spoonleaf Sundew - Beaked Spikerush Coastal Fen (CEGL006310)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Tidal Salt Marsh (CES203.519)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana (eastern red cedar)

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Baccharis halimifolia (groundsel-tree)

- Iva frutescens (salt marsh-elder)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry)

-

Herbs

- Andropogon glomeratus var. glomeratus (bushy bluestem)

- Cladium mariscoides (twig-rush)

- Eleocharis rostellata (walking spike-rush)

- Iris prismatica (slender blue iris, slender blue flag)

- Juncus canadensis (Canada rush)

- Sanguisorba canadensis (Canadian burnet)

- Schoenoplectus americanus (chair-maker's bulrush)

- Spartina patens (salt-meadow cord grass)

- Teucrium canadense (American germander)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal plain poor fen

(guide)

Sea level fens are located at the upper most position in salt marshes where there is sufficient fresh groundwater seepage. This is a weakly minerotrophic peatland that occurs on the coastal plain, in which the substrate is peat composed primarily of Sphagnum, with admixtures of graminoid and woody peat. The dominant species are Sphagnum mosses, with scattered sedges, shrubs, and stunted trees. Poor fens are fed by waters that are weakly mineralized, with low pH values, generally between 4.0 and 5.5 (Andrus 1980). There is usually lower species diversity within coastal plain poor fens compared with sea level fens.

- Inland poor fen

(guide)

This is a weakly minerotrophic peatland that occurs inland from the coastal plain in which the substrate is peat composed primarily of Sphagnum, with admixtures of graminoid or woody peat. The dominant species are Sphagnum mosses, with scattered sedges, shrubs, and stunted trees. Poor fens are fed by waters that are weakly mineralized, and have low pH values, generally between 3.5 and 5.0. Inland poor fens have much less species diversity compared to sea level fen. These fens occur north of the coastal lowlands zone and are not influenced by maritime processes.

- Maritime freshwater interdunal swales

(guide)

This is a mosaic of wetlands that occur in low areas between dunes along the Atlantic coast; the low areas are formed either by blowouts in the dunes that lower the soil surface to groundwater level, or by the seaward extension of dune fields. The dominant species are sedges and herbs; low shrubs are usually present, but they are never dominant. These wetlands may be quite small (less than 0. 25 acre or 0. 1 ha) and species diversity is usually low.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Sea Level Fen. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Andrus, R.E. 1980. Sphagnaceae (Peat Moss Family) of New York State. Bulletin No. 442. New York State Museum. Albany, NY.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Ludwig, J.C. 1995. An overview of sea-level fens. Unpublished report. Virginia Division of Natural Heritage, Richmond, VA.

MacDonald, Dana and Gregory Edinger. 2000. Identification of reference wetlands on Long Island, New York. Final report prepared for the Environmental Protection Agency, Wetland Grant CD992436-01. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 106 pp. plus appendices.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated October, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Shereen Brock

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 13, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Sea level fen.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/sea-level-fen/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.