Coastal Plain Pond Shore

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Mineral Soil Wetlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

The first thing you might notice about a coastal plain pond is that there is no stream flowing in and none flowing out. Water levels of the pond, and therefore the size of the exposed pond shore, are due only to changes in an underground aquifer. During the wetter parts of the year this aquifer is high and water levels in the pond are high which translates into a very narrow pond shore. Conversely, during the dry months (late summer) the aquifer is low so water levels are low but there is a large expanse of pond shore. Every 5 years or so there is an exceptionally dry year with a lot of pond shore exposed. Plants that may not have been seen for a decade will now germinate and grow (Edinger et al 2002, Swain and Keasley 2001).

State Ranking Justification

There are over 30 documented principal occurrences of coastal plain pond shores in New York. Three of those principal occurrences are comprised of 8-13 individual pond shore sub-occurrences each. They are restricted to the coastal plain of Long Island. Many of these systems continue to be threatened by development, invasive species, changes to hydrology, and recreation (e.g., off-road vehicles and trampling).

Short-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of coastal plain pond shores in New York have declined in recent years. There are less than 400 acres currently mapped with probably less than 1000 acres extant. The total, historical, acreage is unknown but was probably less than 2000 acres. The decline is due primarily to development and the increasing demand for freshwater.

Long-term Trends

The numbers and acreage of coastal plain pond shores have declined from historical numbers primarily due to settlement of the area and the corresponding agricultural, residential, and commercial development causing both a displacement of this community and a lowering of the water table due to an increased demand for freshwater.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Invasive species are the primary threat to coastal plain pond shores. Phragmites australis has invaded over half of the documented occurrences (per NY iMapInvasives 2018). Coastal plain pond shores are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., residential, roads), recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, hiking trails causing erosion and compaction), and habitat alteration in the adjacent landscape (e.g., logging, pollution, nutrient loading). Alteration to the natural hydrology is also a threat to this community (e.g., excessivive long-term drawdown and/or flooding, draining, or dredging). Some coastal plain pond shores are too small to be protected by the New York State freshwater wetland regulations. In 2001, the federal Supreme Court ruled that the US Congress did not give authority to the US Army Corps of Engineers (US ACE) under section 404 of the Clean Water Act to regulate the filling of isolated wetlands.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities, minimize actions that will change what the water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually create an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

This natural community has been well searched for in New York but composition and dynamics are just beginning to be documented and will need addtional work.

Research Needs

Research on these pond systems could include evaluating the effect of secondary disturbances such as fire in the surrounding upland forest on the pond shore, evaluating the effect of elevation in the landscape on the species composition of the pond shore, and determining the variation of the species composition of the plant zones around the pond shore between ponds and pond systems. Other research on these pond shores should involve monitoring of invasive species including exotic fish, monitoring hydrologic changes, and monitoring ponds for eutrophication.

Rare Species

- Aletris farinosa (White Colicroot) (guide)

- Ambystoma tigrinum (Tiger Salamander) (guide)

- Amphicarpum amphicarpon (Peanut Grass) (guide)

- Angelica lucida (Sea-coast Angelica) (guide)

- Bartonia paniculata ssp. paniculata (Green Screwstem) (guide)

- Carex barrattii (Barratt's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex mitchelliana (Mitchell's Sedge) (guide)

- Coreopsis rosea (Rose Coreopsis) (guide)

- Cyperus flavescens (Yellow Flat Sedge) (guide)

- Cyperus polystachyos var. texensis (Coast Flatsedge) (guide)

- Cyperus subsquarrosus (Small-flowered Dwarf Bulrush) (guide)

- Dichanthelium wrightianum (Wright's Rosette Grass) (guide)

- Edrastima uniflora (Clustered Bluets) (guide)

- Eleocharis ambigens (Ambiguous Spike Rush) (guide)

- Eleocharis engelmannii (Engelmann's Spike Rush) (guide)

- Eleocharis equisetoides (Horsetail Spike Rush) (guide)

- Eleocharis tenuis var. pseudoptera (Sharp-angled Spike Rush) (guide)

- Eleocharis tricostata (Three-ribbed Spike Rush) (guide)

- Eleocharis tuberculosa (Long-tubercled Spike Rush) (guide)

- Eleocharis uniglumis (Single-glumed Spike Rush) (guide)

- Enallagma laterale (New England Bluet) (guide)

- Enallagma minusculum (Little Bluet) (guide)

- Enallagma pictum (Scarlet Bluet) (guide)

- Enallagma recurvatum (Pine Barrens Bluet) (guide)

- Erynnis martialis (Mottled Duskywing) (guide)

- Eupatorium leucolepis var. leucolepis (White-bracted Boneset) (guide)

- Eupatorium subvenosum (Veined Thoroughwort) (guide)

- Eupatorium torreyanum (Torrey's Thoroughwort) (guide)

- Hydrocotyle verticillata (Whorled-pennywort) (guide)

- Hypericum adpressum (Creeping St. John's Wort) (guide)

- Hypericum denticulatum (Coppery St. John's Wort) (guide)

- Iris prismatica (Slender Blue Flag) (guide)

- Juncus biflorus (Large Grass-leaved Rush) (guide)

- Juncus debilis (Weak Rush) (guide)

- Lachnanthes caroliniana (Carolina Redroot) (guide)

- Lespedeza angustifolia (Narrow-leaved Bush Clover) (guide)

- Libellula auripennis (Golden-winged Skimmer) (guide)

- Ludwigia sphaerocarpa (Globe-fruited Seed-Box) (guide)

- Lycopus amplectens (Clasping Water Horehound) (guide)

- Lysimachia hybrida (Lowland Loosestrife) (guide)

- Myriophyllum pinnatum (Cut-leaved Water Milfoil) (guide)

- Oxybasis rubra var. rubra (Red Pigweed) (guide)

- Persicaria careyi (Carey's Smartweed) (guide)

- Persicaria setacea (Bristly Smartweed) (guide)

- Potentilla anserina ssp. pacifica (Coastal Silverweed) (guide)

- Proserpinaca pectinata (Comb-leaved Mermaid Weed) (guide)

- Rhynchospora inundata (Horned Beak Sedge) (guide)

- Rhynchospora nitens (Short-beaked Beak Sedge) (guide)

- Rhynchospora scirpoides (Long-beaked Beak Sedge) (guide)

- Rotala ramosior (Toothcup) (guide)

- Sagittaria teres (Quill-leaved Arrowhead) (guide)

- Scleria triglomerata (Whip Nut Sedge) (guide)

- Stachys hyssopifolia var. hyssopifolia (Hyssop Hedge Nettle) (guide)

- Utricularia juncea (Rush Bladderwort) (guide)

- Utricularia striata (Striped Bladderwort) (guide)

- Viola primulifolia (Primrose-leaf Violet) (guide)

- Xyris smalliana (Large Yellow-eyed Grass) (guide)

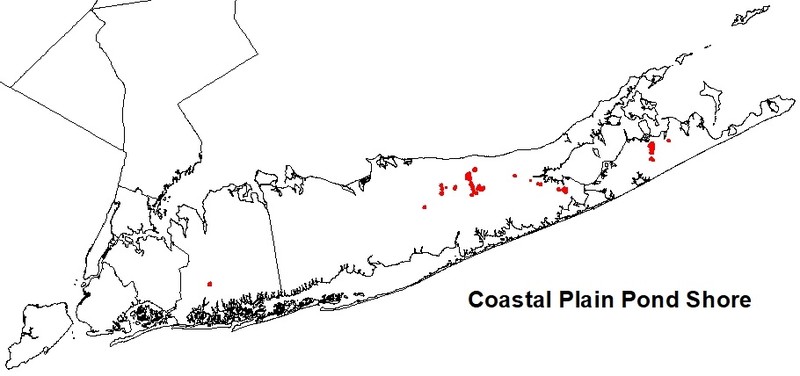

Range

New York State Distribution

Coastal plain pond shores are restricted to coastal lowlands in Suffolk County where they occur on the gently sloping shores of coastal plain ponds with fluctuating water levels. They occur where the substrate is sandy or gravelly and the water levels are tied to the underground aquifer.

Global Distribution

This oligotrophic (nutrient poor) coastal plain pondshore community occurs on the shores of ponds formed in glacial outwash plains. They can be found from Ontario and Nova Scotia south to Long Island, New York, and to the coastal plain of New Jersey. The substrate is generally sand or gravelly sand with a shallow or negligible organic layer.

Best Places to See

- Rocky Point Natural Resources Management Area (Suffolk County)

- Brookhaven State Park (Suffolk County)

- Hempstead Lake State Park (Nassau County)

- Sears Bellows County Park (Suffolk County)

- Peconic River Significant Coastal Fish and Wildlife Habitat (Suffolk County)

- Otis Pike Preserve (Suffolk County)

- David A. Sarnoff Pine Barrens Preserve (Suffolk County)

- Long Pond Greenbelt Significant Coastal Fish and Wildlife Habitat (Suffolk County)

- Long Pond Greenbelt Preserve (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A gently sloping shore of a coastal plain pond with seasonally and annually fluctuating water levels. The plant cover varies with the changing water levels. In dry years when water levels are low, there is a dense growth of annual sedges, grasses, and herbs. This vegetation occurs in distinctive zones or rings around the pond. In wet years when the water level is high the vegetation is sparse. The fluctuating water level also keeps woody vegetation from getting established. The dominant vegetation is often grass like and includes spikerush (Eleocharis parvula), beakrush (Rhynchospora capitellata) and pipewort (Eriocaulon aquaticum).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Coastal plain pond shores are found exclusively in the coastal plain of Long Island in New York state. The community occupies the gentle slopes of ponds formed in the glacial till. When water levels are low, distinctive zones or rings of herbaceous vegetation form around the pond.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 10 feet and 60 feet.

Best Time to See

The best time to visit this community is probably during the late summer when the water levels are lowest and the exposed pond shore is largest. Zones of plants from the waters edge to the tree line will be evident along with the greatest number of growing plant species.

Coastal Plain Pond Shore Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Smooth Sawgrass - Horsetail Spikerush Marsh (CEGL006016)

- (Blunt Spikerush, Yellow Spikerush) - Seven-angle Pipewort Marsh (CEGL006261)

- American White Water-lily - Robbins' Spikerush Aquatic Vegetation (CEGL006086)

- Virginia Meadowbeauty - Arrowhead Rattlebox Marsh (CEGL006300)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Pond (CES203.518)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Lyonia mariana (staggerbush)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry)

-

Tree seedlings

- Chamaecyparis thyoides (Atlantic white cedar)

-

Herbs

- Agalinis purpurea (purple agalinis)

- Calamagrostis canadensis

- Carex striata (Walter's sedge)

- Cladium mariscoides (twig-rush)

- Coreopsis rosea (pink coreopsis, pink tickseed)

- Cyperus dentatus (toothed flat sedge)

- Cyperus filicinus (fern flat sedge)

- Dichanthelium meridionale (southern rosette grass)

- Dichanthelium wrightianum (Wright's rosette grass)

- Drosera filiformis (thread-leaved sundew)

- Drosera intermedia (spatulate-leaved sundew)

- Eleocharis flavescens var. olivacea (olive-fruited spike-rush)

- Eleocharis melanocarpa (black-fruited spike-rush)

- Eleocharis obtusa var. obtusa (blunt spike-rush)

- Eleocharis parvula (salt-loving spike-rush)

- Eleocharis robbinsii (Robbins's spike-rush)

- Eleocharis tuberculosa (large-tubercled spike-rush)

- Eriocaulon aquaticum (northern pipewort, northern hat-pins)

- Eupatorium perfoliatum (boneset)

- Euthamia caroliniana (slender flat-topped-goldenrod)

- Fuirena pumila (dwarf umbrella-grass)

- Gratiola aurea (golden hedge-hyssop)

- Hypericum adpressum (creeping St. John's-wort)

- Hypericum canadense (lesser Canadian St. John's-wort)

- Hypericum virginicum (Virginia marsh St. John's-wort)

- Iris prismatica (slender blue iris, slender blue flag)

- Juncus acuminatus (sharp-fruited rush)

- Juncus articulatus (jointed rush)

- Juncus canadensis (Canada rush)

- Juncus militaris (bayonet rush)

- Juncus pelocarpus (brown-fruited rush)

- Kellochloa verrucosa (warty panic grass)

- Lachnanthes caroliniana (Carolina redroot)

- Lobelia nuttallii (Nuttall's lobelia)

- Ludwigia sphaerocarpa (globe-fruited seed-box)

- Lycopodiella appressa (appressed-leaved bog-clubmoss, swamp bog-clubmoss)

- Lycopodiella inundata (northern bog-clubmoss)

- Lycopus amplectens (clasping bugleweed, clasping water-horehound)

- Nymphoides cordata (little floating-heart)

- Pluchea odorata (salt marsh-fleabane)

- Proserpinaca pectinata (comb-leaved mermaid-weed)

- Rhexia virginica (Virginia meadow-beauty)

- Rhynchospora alba (white beak sedge)

- Rhynchospora capitellata (brownish beak sedge)

- Rhynchospora inundata (horned beak sedge)

- Rhynchospora macrostachya (tall horned beak sedge)

- Rhynchospora nitens (short-beaked beak sedge)

- Rhynchospora scirpoides (long-beaked beak sedge)

- Sagittaria teres (quill-leaved arrowhead)

- Schoenoplectus pungens var. pungens (three-square bulrush)

- Scleria reticularis (netted nut sedge)

- Utricularia juncea (rush bladderwort)

- Utricularia purpurea (purple bladderwort)

- Utricularia striata (striped bladderwort)

- Utricularia subulata (zigzag bladderwort)

- Xyris difformis var. difformis (bog yellow-eyed-grass)

- Xyris smalliana (Small's yellow-eyed-grass, large yellow-eyed-grass)

- Xyris torta (slender yellow-eyed-grass)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Sphagnum spp.

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal plain pond

(guide)

Coastal plain pond communities are the aquatic community of the permanently flooded portion of a coastal plain pond with seasonally, and annually fluctuating water levels.

- Coastal plain poor fen

(guide)

Coastal plain poor fens are also found on glacial moraine but form best in small "delta-like" areas of organic deposits near the small stream outlets of coastal plain pond basins. They are typically more shrubby than coastal plain ponds.

- Marl pond shore

(guide)

These pond shore communities are similar in that they are both located at the upper fringe of ponds that usually draw down in most years. However, marl pond shores have high pH, marl deposits on gravel substrate and vegetation, with a mat of stranded stoneworts (Chara sp.), located in the limestone areas of central NY. Whereas, coastal plain pond shores are more acidic, lack marl deposits and stoneworts, and are restricted to sandy areas of Long Island.

- Pine barrens vernal pond

(guide)

Pine barrens vernal ponds are also seasonally fluctuating, groundwater-fed ponds. Within the pine barren landscape, this community forms in low kettlehole depressions or in swales between forested dunes. The water is intermittent, typically vernally ponded, and circumneutral.

- Shallow emergent marsh

(guide)

This community is a marsh meadow community that occurs on mineral soil or deep muck soils (rather than true peat), that are permanently saturated and seasonally flooded. The vegetation is typically graminoid (grasses, sedges, and rushes)

- Vernal pool

(guide)

A vernal pool is an aquatic community that can have a wide shoreline. Vernal pools are typically flooded in spring or after a heavy rainfall, but usually dry during summer. Many vernal pools are filled again in autumn.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Coastal Plain Pond Shore. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Boone, D.D. (undated). Rare vascular plants that may be found in coastal plain ponds. Maryland Natural Heritage Program, Annapolis, MD.

Briggs, N. 1993. Habitat use by the lateral bluet damselfly, Enallagma laterale, and the barrens bluet damselfly, Enallagma recurvatum, on seven coastal plain ponds in southern Rhode Island: implications for monitoring and preserve design. Unpublished report to the Nature Conservancy, March 19, 1993. 14 pp.

Brown, Lauren. 1979. Grasses An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin Co. 2 Park St. Boston, MA. 021098. B79BRO01PAUS.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Enser, R.W. Observations concerning two types of coastal plain ponds in Rhode Island. unpublished report for Rhode Island Natural Heritage Program, Providence.

Graham, H.W. and L.K. Henry. 1933. Plant succession at the borders of a Kettle-Hole Lake. Bulletin Torrey Botanical Club 60:301-314.

Klockner, Wayne. 1986. More on coastal plain Ponds. Eastern Region Science and Stewardship Newsletter 2:1-3.

Lundgren, J. A. 1987. The distribution and occurrence of the vegetation of a coastal plain pond shore in Plymouth, MA from 1986 to 1987. Unpubl. report submitted to Massachusetts Natural Heritage Program. Boston, MA 11 pp. Draft.

Lundgren, J.A. 1989. Distribution and phenology of pondshore vegetation at a coastal plain pond in Plymouth, Massachusetts. M.S. thesis. University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 80 pp.

MacDonald, Dana and Gregory Edinger. 2000. Identification of reference wetlands on Long Island, New York. Final report prepared for the Environmental Protection Agency, Wetland Grant CD992436-01. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 106 pp. plus appendices.

McAvoy, W., and K. Clancy. 1994. Community classification and mapping criteria for Category I interdunal swales and coastal plain pond wetlands in Delaware. Final Report submitted to the Division of Water Resources in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. 47 pp.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Parker, Dorothy. 1946. Plant succession at Long Pond, Long Island, New York. Butler University Bot. Studies 7:74-88.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Schneider, R. 1992. Examination of the role of hydrology and geochemistry in maintaining rare plant communites of coastal plain ponds. report to the Nature Conservancy. DC.

Schneider, R. 1994. The role of hydrologic regime in maintaining rare plant communities of New York's coastal plain pondshores. Biological Conservation 68:253-260.

Sneddon, L. A. 1994. Descriptions of coastal plain pondshore proposed community elements. Unpublished. The Nature Conservancy, Boston, MA.

Sneddon, L. A., M. Anderson, and J. Lundgren. 1999. Classification of coastal plain pondshore communities of the Cape Cod National Seashore using the U.S. National Vegetation Classification. Unpublished report to the Cape Cod National Seashore. The Nature Conservancy, Boston, MA.

Sneddon, L. A., and M. G. Anderson. 1994. A classification scheme for Coastal Plain pondshore and related vegetation from Maine to Virginia. Supplement to Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 77 (Abstract).

Sorrie, Bruce. 1986. Comments on New England coastal plain ponds. Eastern Region Science and Stewardship Newsletter 2:3-5.

South Fork Natural History Society. 1993. South Fork natural history newsletter: Special issue - The Long Pond Greenbelt. South Fork Natural History Newsletter 5 (1). Amagansett, NY 11930.

Swain, P. C., and J. B. Kearsley. 2001. Classification of natural communities of Massachusetts. September 2001 draft. Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

Theall, O. 1983. An investigation into the hydrology of massachusetts' coastal plain ponds. unpublished report for Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife.

Theall, Otto. 1983. An investigation into the hydrology of Massachusetts' coastal plain pond. Unpublished study by Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife.

Williams, D.D. 2001. The Ecology of temporary waters. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, NJ.

Zaremba, R. E., and E. E. Lamont. 1993. The status of the Coastal Plain pondshore community in New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 120:180-187.

Zaremba, Robert E. 1991. Notes on EO rank changes or ID changes for 17 coastal plain pond shore sites, faxed February 25, 1991.

Zebryk, Tad M. 2004. Inland sandy acid pondshores in the lower Connecticut River Valley, Hamden County, Massachusetts. Rhodora 106:(925): 66-76.

Links

About This Guide

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Coastal plain pond shore.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/coastal-plain-pond-shore/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.