Salt Panne

- System

- Estuarine

- Subsystem

- Estuarine Intertidal

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1S2

Critically Imperiled or Imperiled in New York - Especially or very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 20 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines. More information is needed to assign either S1 or S2.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

Glasswort (Salicornia and Sarcocornia) are a characteristic succulent plant of salt pannes. The stems are transparent like colored glass and in the fall, they turn brilliant red.

State Ranking Justification

There are estimated to be between 10 and 25 occurrences of this community statewide. The several documented occurrences have good viability and are protected on public land or private conservation land. The community is restricted to salt marshes along the seacoast of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone, and is best developed on the south shore of Long Island, especially in areas of low mean tidal range. The current trend of the community is declining. Substantial primary threats, common to all salt marsh complexes, include ditching and draining, dredging and filling, common reed (Phragmites australis) invasion, poor water quality, diking and impoundment, inlet stabilization, shoreline hardening, wrack accumulation, altered sediment budget, subsidence, changes in water circulation patterns, restricted tidal connection, and altered tidal hydrodynamics.

Short-term Trends

In recent decades, the number, aerial extent, and quality of low and high salt marshes in New York has declined significantly. Salt pannes, which develop in these marshes, are suspected to have suffered equally drastic declines. It is speculated that these losses are linked to the public works projects of the 1930s, including dredging and filling for major airport construction and urban development. Declines have also been due to ditching for mosquito control; production of salt hay as a forage crop for livestock; and to pollution, including airborne particulates, pesticides, and sewage and stormwater discharge. It is suspected that losses will continue, resulting from ongoing shoreline development, declining water quality, and hydrologic alterations.

Long-term Trends

The number, aerial extent, and integrity of salt marshes and associated salt pannes in New York are suspected to have declined substantially from their historical state. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development; dredging, ditching, and filling; and changes in hydrology, water quality, and natural processes.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Factors that threaten low and high salt marsh also threaten salt panne communities. These include dredging and filling for development, ditching and draining for mosquito control, common reed (Phragmites australis) invasion, poor water quality (from sewage and stormwater discharge; nonpoint source runoff; landfill leachate; boat traffic; particulate aircraft, vehicular, and power plant emissions; jet fuel; ethylene glycol from aircraft deicing; and pesticides used in mosquito management), diking and impoundment, inlet stabilization, shoreline hardening, wrack accumulation, altered sediment budget (decreased sediment input to marshes), subsidence, changes in water circulation patterns because of changes in shoreline and benthic topography, restricted tidal connection, and altered tidal hydrodynamics resulting from changes to hydrology (including groundwater levels, overland flow, and in-channel volume) in the surrounding watershed, road construction, and urbanization (GNRA and JBWPPAC 2007, Niedowski 2000, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation 2009b, 2009c, 2009d).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Monitor the abundance of invasive species, particularly common reed (Phragmites australis), in this community and, as needed, control their encroachment. Remove shoreline armoring to increase overland sediment input; improve water quality by reducing or eliminating sewer and stormwater discharge and pesticide application; restore tidal regime by removing culverts, dikes, and impoundments, plugging ditches, and replacing static flow restriction devices with those that are calibrated for local tidal hydrology. Restoration and monitoring protocols are available (Niedowski 2000).

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize or eliminate hardened shorelines and maintain low-sloped shorelines within the tidal zone to increase overland sediment input. Maintain functional connectivity between the open ocean and bays with salt marsh complexes to enable full tidal flushing during each tidal cycle. For example, barriers such as railway causeways should have numerous culverts to allow sufficient hydrologic connectivity. If flow restriction devices are needed, those that are calibrated for local tidal hydrology can be used. Avoid dumping dredge spoil onto salt pannes. This community is best protected as part of a large salt marsh complex. Protected areas should encompass the full mosaic of low salt marsh, high salt marsh, marine intertidal mudflats, saltwater tidal creek, salt panne, and salt shrub communities to allow dynamic ecological processes (sedimentation, erosion, tidal flushing, and nutrient cycling) to continue. Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities, upland beaches and dunes, and to shallow offshore communities should be maintained. Connectivity between these habitats is important not only for nutrient flow and seed dispersal, but also for animals that move between them seasonally. Development of site conservation plans that identify wetland threats and their sources and provide management and protection recommendations would ensure their long-term viability.

Inventory Needs

Additional inventory is needed on the north and south shore of Long Island and in Peconic Bay. Leads include sites that were not selected as reference wetlands by MacDonald and Edinger (2000). Sites on the north shore include Lloyd Neck Marsh and Flax Pond. The remaining south shore lead is at Apple Tree Neck Wetlands. Sites in the Peconic Bay are Bass Creek Marsh, Miss Annies Creek Marsh, Northwest Creek, and West Creek.

Research Needs

Future research on salt pannes should address the classification of the pond-like variant dominated by widgeon-grass (Ruppia maritima). A comparison of this community with coastal salt pond also needs to be made. Other research should investigate the role of salt pannes in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling to determine their rate of export and import of nutrients to the marsh surface. Additional beneficial research could explain the role of pannes in marsh surface formation (e.g., are they growing, shrinking, or fairly permanent features?) and more study is needed to understand the use of salt pannes by birds (e.g., what species use pannes and why?) (MacDonald and Edinger 2000).

Rare Species

- Ammodramus maritimus (Seaside Sparrow) (guide)

- Asio flammeus (Short-eared Owl) (guide)

- Atriplex dioica (Thick-leaved Orach) (guide)

- Bubulcus ibis (Cattle Egret) (guide)

- Charadrius melodus (Piping Plover) (guide)

- Circus hudsonius (Northern Harrier) (guide)

- Egretta caerulea (Little Blue Heron) (guide)

- Egretta thula (Snowy Egret) (guide)

- Egretta tricolor (Tricolored Heron) (guide)

- Gelochelidon nilotica (Gull-billed Tern) (guide)

- Laterallus jamaicensis (Black Rail) (guide)

- Nyctanassa violacea (Yellow-crowned Night-Heron) (guide)

- Plegadis falcinellus (Glossy Ibis) (guide)

- Salicornia bigelovii (Bigelow's Glasswort) (guide)

- Sterna dougallii (Roseate Tern) (guide)

- Sterna forsteri (Forster's Tern) (guide)

- Sterna hirundo (Common Tern) (guide)

- Sternula antillarum (Least Tern) (guide)

- Tyto alba (Barn Owl) (guide)

Range

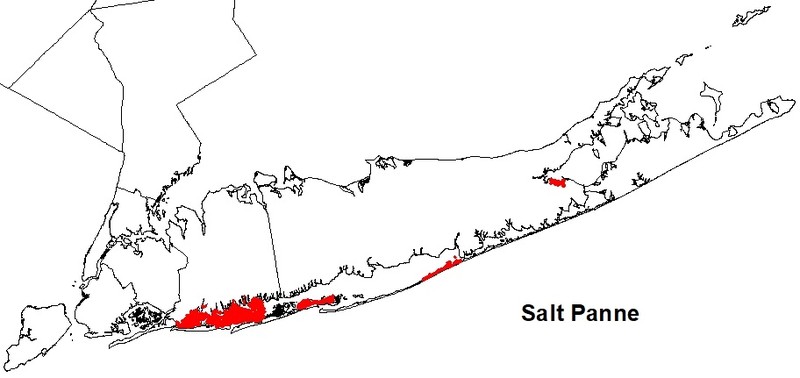

New York State Distribution

Salt pannes are restricted to salt marshes along the seacoast of the Coastal Lowlands ecozone. Salt pannes are best developed on the south shore of Long Island, especially in areas of low mean tidal range. They are poorly developed in the Peconic Bay and very poorly developed on the north shore of Long Island.

Global Distribution

This community occurs along the Mid- and North Atlantic Coast from the Canadian maritime provinces south to North Carolina (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Gilgo State Park (Suffolk County)

- Jones Beach State Park (Nassau County)

- Captree State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A shallow depression in a salt marsh where the marsh is poorly drained. Pannes occur in both low and high salt marshes. Pannes in low salt marshes usually lack vegetation, and the substrate is a soft, silty mud. Pannes in a high salt marsh are irregularly flooded by spring tides or flood tides, but the water does not drain into tidal creeks. After a panne has been flooded the standing water evaporates and salinity of the soil water is raised well above the salinity of sea-water. Soil water salinities fluctuate in response to tidal flooding and rainfall. Small pond holes occur in some pannes; the pond holes are usually deeper than the thickness of the living salt marsh turf, and the banks or "walls" of the pond holes are either vertical or they undercut the peat. Salt pannes can be formed by ponding of water on the marsh surface, scouring of wrack or coverage by storm wrack, and possibly by ice scour. Salt panne formation appears to be favored by a mean tidal range of about 20-80 cm and are poorly developed in settings with a mean tidal range greater than 1.6 m.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic plants of a salt panne include the dwarf form (15 to 30 cm tall) of cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), glassworts (Salicornia depressa and Sarcocornia pacifica), marsh fleabane (Pluchea odorata), salt marsh plantain (Plantago maritima ssp. juncoides), arrow-grass (Triglochin maritimum), spikegrass (Distichlis spicata), sea-blites (Suaeda spp.), and salt marsh sand spurry (Spergularia marina). High salt marsh communities that are dominated by the dwarf form of Spartina alterniflora appear to support larger, better developed pannes than marshes dominated by S. patens and Distichlis spicata. Widgeon-grass (Ruppia maritima) grows in the pond holes; fishes that may be permanent residents in large pond holes include mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus) and sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus). The salt pannes on the south shore of Long Island are intensely used by feeding shorebirds. A characteristic butterfly of salt pannes is the salt marsh skipper (Panoquina panoquin) where the caterpillar feeds on spikegrass (Glassberg 1999).

Best Time to See

Salt marsh sand spurry, a small salt panne plant with white to bright pink petals, comes into flower in midsummer (July/August). Also at that time, salt-meadow grass in surrounding high salt marshes has become tall enough to develop the flattened, circular 'cowlick' growth form that is characteristic of that community. This species also blooms in midsummer, and its large florets provide a great opportunity to examine the unique structure of graminoid flowers.

Salt Panne Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Widgeongrass - Sago Pondweed Aquatic Vegetation (CEGL006370)

- (Virginia Glasswort, Dwarf Saltwort, Slender Grasswort) - Smooth Cordgrass Salt Marsh (CEGL004308)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Tidal Salt Marsh (CES203.519)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Iva frutescens (salt marsh-elder)

-

Herbs

- Chenopodium album (lamb's-quarters, pigweed)

- Distichlis spicata (salt grass)

- Eleocharis parvula (salt-loving spike-rush)

- Limonium carolinianum (sea-lavender)

- Phragmites australis (old world reed grass, old world phragmites)

- Salicornia bigelovii (Bigelow's glasswort)

- Salicornia depressa (slender glasswort)

- Spartina alterniflora (smooth cord grass)

- Spartina patens (salt-meadow cord grass)

- Spergularia marina (lesser salt marsh sand-spurry)

- Suaeda maritima ssp. maritima (white sea-blite)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Ulva lactuca

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal salt pond

(guide)

While both communities may have widgeon-grass (Ruppia maritima) growing in the open water portion of the community, salt pannes typically form within large areas of high salt marsh, whereas coastal salt ponds form behind dunes with a small inlet that may fill with sand and occasionally close.

- High salt marsh

(guide)

High salt marsh is dominated by salt-meadow grass (Spartina patens), spikegrass, dwarf-form cordgrass, and black-grass (Juncus gerardii); glassworts are present but in lower relative abundance. In salt panne, however, glassworts are dominant and characteristic.

- Marine intertidal mudflats

(guide)

Marine intertidal mudflats are largely unvegetated communities; the substrate, which is silt or sand, may be covered with marine algae. Salt pannes are often vegetated and, if not, have a silty mud substrate with extremely high soil water salinity.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Salt Panne. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Egler, F.E. 1950. Regional vegetation literature. III. Massachusetts. Phytologia 3: 193-237.

Gateway National Recreation Area and Jamaica Bay Watershed Protection Plan Advisory Committee. 2007. An update on the disappearing salt marshes of Jamaica Bay, New York. Prepared by Gateway National Recreation Area, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior and Jamaica Bay Watershed Protection Plan Advisory Committee, August 2, 2007.

Glassberg, J. 1999. Butterflies Through Binoculars: The East. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 400 pp.

MacDonald, Dana and Gregory Edinger. 2000. Identification of reference wetlands on Long Island, New York. Final report prepared for the Environmental Protection Agency, Wetland Grant CD992436-01. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 106 pp. plus appendices.

Miller, W.B. and F.E. Egler. 1950. Vegetation of the Wequetequock-Pawcatuck tidal marshes, Connecticut. Ecol. Monogr. 20:143-172.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated July 17, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2009b. Tidal wetland losses, Jamaica Bay, Queens County, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2009c. Tidal wetland losses, Nassau and Suffolk Counties.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2009d. Tidal wetland losses, Strategy for Addressing Loss of Intertidal Marsh in the Marine District.

Niedowski, N.L. 2000. New York State salt marsh restoration and monitoring guidelines. Prepared for New York Department of State, Albany, NY, and New York Department of Environmental Conservation, East Setauket, NY.

Nixon, S.W. 1982. The ecology of New England high salt marshes: A community profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Biological Services, Washington D.C. FWS/OBS-81/55. 70 pp.

Packham, J.R. and A.J. Willis. 1997. Ecology of Dunes, Salt Marsh and Shingle. Chapman and Hall, London.

Redfield, A. C. 1972. Development of a New England salt marsh. Ecological Monographs 42:201-37.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: June 6, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Salt panne.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/salt-panne/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.