Deep Emergent Marsh

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Mineral Soil Wetlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G5

Secure globally - Common in the world; widespread and abundant (but may be rare in some parts of its range).

Summary

Did you know?

A characteristic species found in deep emergent marshes is wild rice (Zizania aquatica and Z. palustris). In addition to providing habitat and food for marsh fish and waterfowl, wild rice has been an important food staple for Native Americans for thousands of years. The ancestral grain of wild rice has even been found in layers of earth dating back 12,000 years! Today, about 23 million pounds of "wild" wild rice varieties as well as "cultivated" wild rice varieties are produced each year around the world, 4 million of which is considered "wild" grown.

State Ranking Justification

There are several thousand occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and many are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has statewide distribution, and includes a few large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats that include alteration of the natural hydrology and invasive species.

Short-term Trends

Emergent covertype acreage and relative abundance appeared to decline slightly statewide (Huffman & Associates, Inc. 2000). There may be a few cases where this community has increased as a result of flooding from impoundments.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of deep emergent marshes in New York has substantially declined (50-75%) from historical numbers likely correlated to the alteration of the natural hydrology and/or direct destruction.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Deep emergent marshes are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., agriculture, residential, commercial, roads/bridges), habitat alteration (e.g., algal blooms, pollution, dumping, utility ROWs), and recreational overuse (e.g., motor boating, canoeing, fishing). Alteration to the natural hydrological regime is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, dredging, blocked culverts, beaver). Several deep emergent marshes are threatened by invasive species, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), water chestnut (Trapa natans), Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), reedgrass (Phragmites australis), and frog-bit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the wetland. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore past impacts, such as removing obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology. Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of deep emergent marshes. A statewide review of deep emergent marshes is desirable. Continue searching for large sites in excellent to good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Research the influence that artificial lake level control has on the structure and composition of deep emergent marshes. Research is needed to determine the distribution and invasiveness of Typha spp. in deep emergent marshes, including the presence of the hybrid cattail (Typha x glauca) in all examples. Research composition of deep emergent marshes statewide in order to characterize variations. Collect sufficient plot data to support the recognition of several distinct deep emergent marsh types based on composition and by ecoregion (e.g., Zizania spp. dominant, Typha spp. dominant, Sparganium spp. dominant, and broad-leaved aquatics dominant).

Rare Species

- Arigomphus cornutus (Horned Clubtail) (guide)

- Carex atherodes (Wheat Sedge) (guide)

- Carex lupuliformis (False Hop Sedge) (guide)

- Chlidonias niger (Black Tern) (guide)

- Circus hudsonius (Northern Harrier) (guide)

- Cuscuta cephalanthi (Buttonbush Dodder) (guide)

- Cuscuta polygonorum (Smartweed Dodder) (guide)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding's Turtle) (guide)

- Equisetum palustre (Marsh Horsetail) (guide)

- Fagitana littera (Marsh Fern Moth) (guide)

- Hottonia inflata (American Featherfoil) (guide)

- Ixobrychus exilis (Least Bittern) (guide)

- Lithobates kauffeldi (Atlantic Coast Leopard Frog) (guide)

- Lysimachia hybrida (Lowland Loosestrife) (guide)

- Macropis nuda (Common Loosestrife Oil Bee) (guide)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) (guide)

- Podilymbus podiceps (Pied-billed Grebe) (guide)

- Potamogeton diversifolius (Southern Snailseed Pondweed) (guide)

- Potamogeton hillii (Hill's Pondweed) (guide)

- Potamogeton pulcher (Spotted Pondweed) (guide)

- Potamogeton x ogdenii (Ogden's Pondweed) (guide)

- Schoenoplectus heterochaetus (Slender Bulrush) (guide)

Range

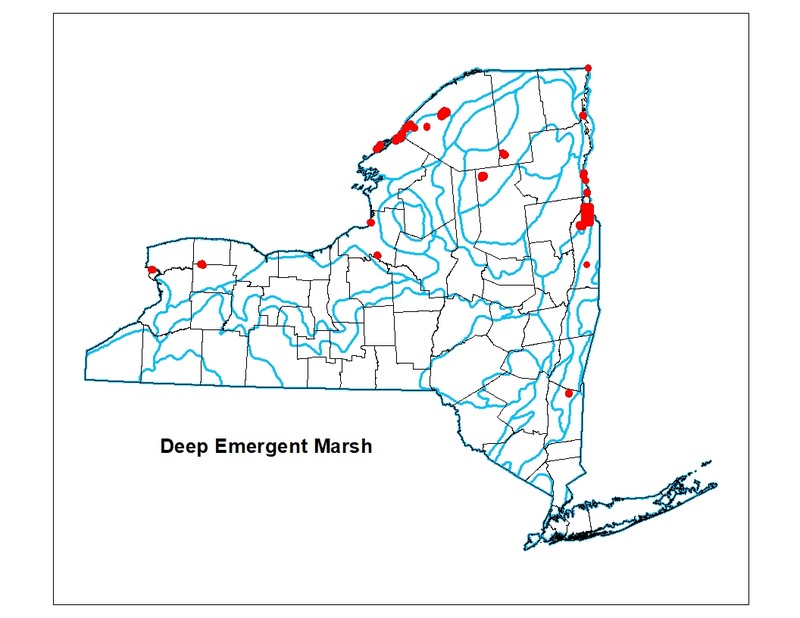

New York State Distribution

This community currently ranges across the northern half of New York where it is often associated with large rivers or lakes. Several deep emergent marshes are known from the St. Lawrence and Lake Champlain Valleys. A few examples are known from the eastern shore of Lake Ontario, the central Adirondacks, the Taconic Mountain Foothills, and the Niagara River in western New York. Emergent wetlands are relatively uncommon, accounting for only 10 percent, or about 239,000 acres, of the freshwater wetlands statewide in the mid-1990s. Emergent wetland as a covertype is most common in the Appalachian Highlands and Hudson Valley, where it accounts for about 11.5 percent of all wetlands. Emergent wetlands are the least common covertype in the Lake Plains and Coastal Lowlands, where only 8 percent of all wetlands are emergent (Huffman & Associates, Inc. 2000).

Global Distribution

This broadly-defined community is widespread throughout the eastern United States. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are suspected to span north to southern Canada, west to Minnesota, southwest to Indiana and Tennessee, southeast to Georgia, and northeast to Nova Scotia.

Best Places to See

- Ausable Marsh Wildlife Management Area, Adirondack Park

- Buckhorn Island State Park

- Carter Pond Wildlife Management Area (Washington County)

- Three Mile Bay Wildlife Management Area (Oswego County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A marsh community that occurs on mineral soils or fine-grained organic soils; the substrate is flooded by waters that are not subject to violent wave action. Water depths can range from 15 cm to 2 m (6 inches to 6.6 feet); water levels may fluctuate seasonally, but the substrate is rarely dry, and there is usually standing water in the fall. Deep emergent marshes are quite variable. They may be codominated by a mixture of species or have a single dominant species.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A community of non-woody plants growing out of water, where the water remains year-round. Typical examples of deep emergent marshes are dominated by cattail (Typha spp.). They tend not to be very floristically diverse and are continuously flooded throughout the year.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 90 feet and 1,716 feet.

Best Time to See

An exciting time to visit this type of marsh is in spring (end of April and on) when the red-winged blackbirds have returned to nest. The males perch on the tallest emergent vegetation and call to attract mates and defend their territories.

Deep Emergent Marsh Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Bayonet Rush - Seven-angle Pipewort Marsh (CEGL006345)

- Broadleaf Pond-lily - American White Water-lily Aquatic Vegetation (CEGL002386)

- Pickerelweed - Green Arrow-arum - Broadleaf Arrowhead Marsh (CEGL006191)

- (Softstem Bulrush, Hardstem Bulrush) Eastern Marsh (CEGL006275)

- (Narrowleaf Cattail, Broadleaf Cattail) - (Bulrush species) Eastern Marsh (CEGL006153)

- Cattail species - Softstem Bulrush - Mixed Herbs Southern Great Lakes Shore Marsh (CEGL005112)

- (Annual Wild Rice, Northern Wild Rice) Marsh (CEGL002382)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Great Lakes Freshwater Estuary and Delta (CES202.033)

- High Allegheny Wetland (CES202.069)

- Laurentian-Acadian Freshwater Marsh (CES201.594)

- North-Central Interior Freshwater Marsh (CES202.899)

Characteristic Species

-

Nonvascular plants

- Chara globularis (stonewort)

-

Emergent aquatics

- Bolboschoenus fluviatilis (river bulrush)

- Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis (Canada bluejoint grass)

- Juncus militaris (bayonet rush)

- Leersia oryzoides (rice cut grass)

- Peltandra virginica (green arrow-arum, tuckahoe)

- Pontederia cordata (pickerelweed)

- Schoenoplectus acutus var. acutus (hard-stemmed bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus americanus (chair-maker's bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus heterochaetus (slender bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus pungens var. pungens (three-square bulrush)

- Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani (soft-stemmed bulrush)

- Sparganium androcladum (large-fruited bur-reed)

- Sparganium eurycarpum (giant bur-reed)

- Typha angustifolia (narrow-leaved cat-tail)

- Typha latifolia (wide-leaved cat-tail)

- Zizania aquatica var. aquatica (southern wild-rice)

-

Floating-leaved aquatics

- Brasenia schreberi (water-shield)

- Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (European frog's-bit)

- Lemna minor (common duckweed)

- Lemna trisulca (star duckweed)

- Nuphar variegata (common yellow pond-lily, common spatter-dock)

- Nymphaea odorata ssp. odorata (fragrant white water-lily)

- Potamogeton crispus (curly pondweed)

- Potamogeton epihydrus (ribbon-leaved pondweed)

- Potamogeton friesii (Fries's pondweed)

- Potamogeton natans (floating-leaved pondweed)

- Potamogeton oakesianus (Oakes's pondweed)

- Potamogeton pusillus (common narrow-leaved pondweed)

- Potamogeton strictifolius (straight-leaved pondweed)

- Potamogeton zosteriformis (flat-stemmed pondweed)

- Wolffia spp. (watermeal)

-

Submerged aquatics

- Ceratophyllum demersum (common coon-tail)

- Elodea canadensis (Canada waterweed)

- Eriocaulon aquaticum (northern pipewort, northern hat-pins)

- Heteranthera dubia (water star-grass)

- Lobelia dortmanna (water lobelia)

- Myriophyllum sibiricum (northern water milfoil)

- Myriophyllum spicatum (Eurasian water milfoil)

- Najas flexilis (common water-nymph, common naiad)

- Potamogeton amplifolius (big-leaved pondweed)

- Potamogeton crispus (curly pondweed)

- Potamogeton richardsonii (Richard's pondweed)

- Potamogeton spirillus (northern snailseed pondweed)

- Potamogeton zosteriformis (flat-stemmed pondweed)

- Riccia fluitans (thallose liverwort)

- Utricularia intermedia (flat-leaved bladderwort)

- Utricularia vulgaris ssp. macrorhiza (greater bladderwort)

- Vallisneria americana (water-celery, tape-grass)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Eutrophic pond

(guide)

Both communities share several of the same aquatic plant species. Eutrophic ponds are generally deeper (>3 m or 10 feet) than deep emergent marshes (<2 m or 6.6 feet). Deep emergent marshes have at least 10% cover of emergent aquatic plants, whereas emergent aquatic plants are usually around the margin of eutrophic ponds and ideally have an open water component in the deeper areas.

- Great Lakes aquatic bed

(guide)

Both communities share several of the same aquatic plant species. Great Lakes aquatic beds are generally deeper (>3 m or 10 feet) than deep emergent marshes (<2 m or 6.6 feet). Great Lakes aquatic beds have little to no emergent vegetation, whereas deep emergent marshes are dominated by emergent plants.

- Shallow emergent marsh

(guide)

Shallow emergent marsh is better drained than a deep emergent marsh; water depths may range from 15 cm to 1 m (6 inches to 3.3 feet) during flood stages, but the water level usually drops by mid to late summer and the substrate is exposed during an average year.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Deep Emergent Marsh. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Bray, W.L. 1915. The development of the vegetation of New York State. New York State College of Forestry, Tech. Publ. No. 3, Syracuse, NY.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Gilman, B. A. 1976. Wetland plant communities along the eastern shoreline of Lake Ontario. M.S. thesis, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, New York.

Huffman & Associates, Inc. (August 1999) Finalized June 2000. Wetlands Status and Trend Analysis of New York State - Mid-1980's to Mid-1990's. Prepared for New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. June 2000. Larkspur, California. l7pp. plus attachments.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Shereen Brock

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 27, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Deep emergent marsh.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/deep-emergent-marsh/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.