Pine Barrens Vernal Pond

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Mineral Soil Wetlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2

Imperiled in New York - Very vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 20 populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

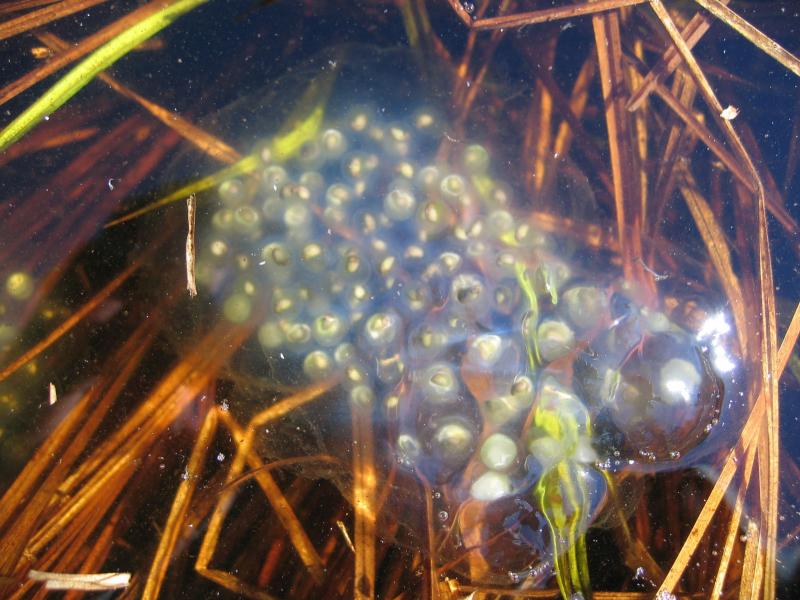

Many species of amphibians and reptiles depend on pine barrens vernal ponds for breeding and feeding. The eastern spadefoot toad, Jefferson salamander, and spotted salamander breed in these ponds, and use surrounding upland and wetland habitats. The eastern hognose snake feeds on the toads that depend on the ponds. Several species of amphibians, including the blue-spotted salamander and wood frog, will only breed in temporary ponds, which are free of the danger of predation by fish.

State Ranking Justification

There are very few occurrences of pine barrens vernal ponds statewide. Some pine barrens vernal ponds are too small to be protected by the New York State freshwater wetland regulations. A few documented occurrences have good viability and are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community has limited statewide distribution and tends to be embedded within pine barrens, which depend on fire to maintain an open habitat. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure, alteration to the natural hydrology, reduced protection regulations for isolated wetlands, and perhaps fire suppression. This community has declined moderately from historical numbers likely correlated with mining, logging, and development of the surrounding landscape.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of pine barrens vernal ponds in New York have probably declined in recent decades as a result of reduced protection regulations for isolated wetlands. Their relatively small size and seasonal hydroperiod may have contributed to the decline with many occurrences going undetected as regulated wetlands.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of pine barrens vernal ponds in New York have declined moderately from historical numbers likely correlated to the alteration to the natural hydrology and direct destruction..

Conservation and Management

Threats

Pine barrens vernal ponds are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., residential, roads), recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, hiking trails causing peat compaction), and habitat alteration in the adjacent landscape (e.g., logging, pollution, nutrient loading). Alteration to the natural hydrology is also a threat to this community (e.g., flooding or draining). Since many vernal ponds are embedded within pine barrens ecosystems, fire suppression may be an additional threat to this community. Although invasive species are currently not a threat to pine barrens vernal ponds, reedgrass (Phragmites australis ssp. australis) and purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) may become a problem in the future. Some pine barrens vernal ponds are too small to be protected by the New York State freshwater wetland regulations.In 2001, the federal Supreme Court ruled that the US Congress did not give authority to the US Army Corps of Engineers (US ACE) under section 404 of the Clean Water Act to regulate the filling of isolated wetlands. This decision led US EPA and US ACE officials to issue guidance in January 2003 that made it more difficult for regulators to protect isolated wetlands, such as pine barrens vernal ponds (Comer et al. 2005).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Where practical, establish and maintain a natural wetland buffer to reduce storm-water, pollution, and nutrient run-off, while simultaneously capturing sediments before they reach the pond. Buffer width should take into account the erodibility of the surrounding soils, slope steepness, and current land use. Wetlands protected under Article 24 are known as New York State "regulated" wetlands. The regulated area includes the wetlands themselves, as well as a protective buffer or "adjacent area" extending 100 feet landward of the wetland boundary (NYS DEC 1995). If possible, minimize the number and size of impervious surfaces in the surrounding landscape. Avoid habitat alteration within the wetland and surrounding landscape. For example, roads and trails should be routed around wetlands, and ideally not pass through the buffer area. If the wetland must be crossed, then bridges and boardwalks are preferred over filling. Restore pine barrens vernal ponds that have been unnaturally disturbed (e.g., remove obsolete impoundments and ditches in order to restore the natural hydrology). Prevent the spread of invasive exotic species into the wetland through appropriate direct management, and by minimizing potential dispersal corridors, such as roads.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities, minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of pine barrens vernal ponds. Finding occurrences with several ponds forming a complex should be a priority. A statewide review of pine barrens vernal ponds is desirable.

Research Needs

Research is needed to fill information gaps about pine barrens vernal ponds, especially to advance our understanding of their classification (e.g., clearly separate from vernal pools and coastal plain ponds), ecological processes (e.g., fire), hydrology, floristic variation, and characteristic fauna. A comparison of pine barrens vernal ponds within various pine barrens is desirable (e.g., Long Island, Albany Pine Bush, Rome Sand Plains, etc.).

Rare Species

- Carex bullata (Button Sedge) (guide)

- Carex styloflexa (Bent Sedge) (guide)

- Carex wiegandii (Wiegand's Sedge) (guide)

- Coreopsis rosea (Rose Coreopsis) (guide)

- Dichanthelium wrightianum (Wright's Rosette Grass) (guide)

- Eleocharis tricostata (Three-ribbed Spike Rush) (guide)

- Hottonia inflata (American Featherfoil) (guide)

- Lestes unguiculatus (Lyre-tipped Spreadwing) (guide)

- Persicaria careyi (Carey's Smartweed) (guide)

- Plebejus melissa samuelis (Karner Blue) (guide)

- Scaphiopus holbrookii (Eastern Spadefoot) (guide)

- Scleria minor (Slender Nut Sedge) (guide)

- Scleria triglomerata (Whip Nut Sedge) (guide)

- Utricularia radiata (Small Swollen Bladderwort) (guide)

Range

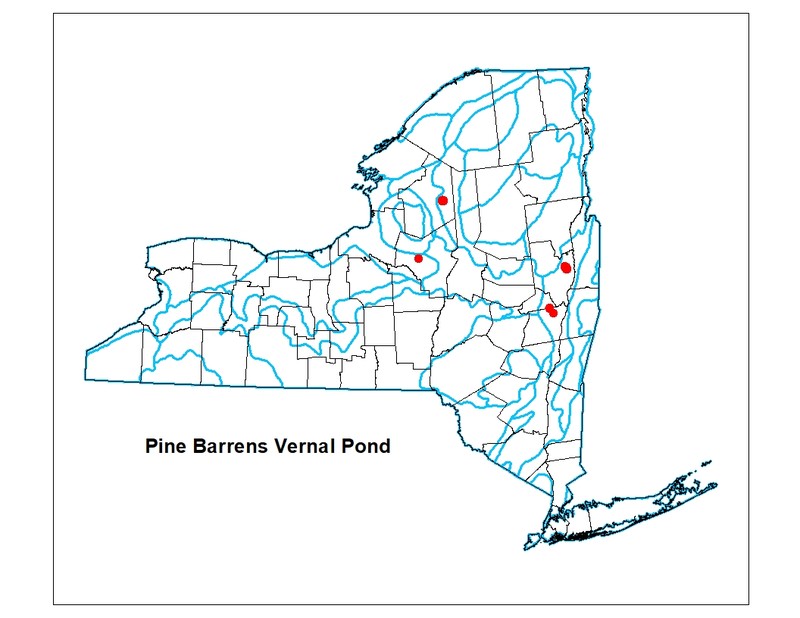

New York State Distribution

Pine barrens vernal ponds are restricted to wet depressions in sand plains. Currently known from the Erie-Ontario plain and from the Hudson Valley. The historical range is unknown, but is probably the same.

Global Distribution

This community is possibly limited to wet depressions in sandplains and estimated to span northwest to southern Ontario and east to southeastern New England. The range outside this area is uncertain including whether or not it occurs in pine barrens of the Upper Midwest U.S. and New Jersey.

Best Places to See

- Independence River Wild Forest, Adirondack Park (Lewis County)

- Rome Sand Planes Unique Area (Oneida County)

- Albany Pine Bush

Identification Comments

General Description

Pine barrens vernal ponds are open, seasonally fluctuating groundwater-fed wetlands within a pine barrens community. They often have a shallow layer of peat over sandy substrate. Some examples of this community have well-developed physiognomic zones, with floating aquatic and submerged species in the deeper sections, emergent species in the shallower water, and woody species along the perimeter. Characteristic herb species include pondweeds (Potamogeton spp.), many sedges (Carex spp., Dulichium arundinaceum, Scirpus cyperinus), marsh St. John's-wort (Triadenum virginicum), and marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris). Shrubs may include highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), and black chokeberry (Photinia melanocarpa). Since pine barrens vernal ponds cannot support fish populations, there is no threat of fish predation on amphibian eggs or invertebrate larvae. Characteristic animals of vernal ponds include species of amphibians, reptiles, crustaceans, mollusks, annelids, and insects. Vernal pond amphibians include spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum), blue-spotted salamander (A. laterale), Jefferson's salamander (A. jeffersonianum), marbled salamander (A. opacum), and wood frog (Rana sylvatica). Fairy shrimp (Anostraca) are obligate vernal pond crustaceans, with Eubranchipus spp. being the most common.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

A seasonally fluctuating, groundwater-fed open wetland within a pine barrens community (or former, fire-suppressed pine barrens community). The vegetation may have a distinct zonation based on water depth, with floating aquatic, submerged, and emergent species toward the middle and woody species along the edges.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 310 feet and 1,290 feet.

Best Time to See

Pine barrens vernal ponds are best observed after spring thaw when they are flooded and breeding wood frogs begin calling. April is generally a good month to visit pine barrens vernal ponds in New York (earlier to the south and later to the north). Repeat visits to the same vernal pond as the water draws down increases the chances of seeing the full array of characteristic species at different stages of their life cycle.

Pine Barrens Vernal Pond Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Threeway Sedge - Canadian Rush - Brown-fruit Rush Marsh (CEGL006415)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Pond (CES203.518)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Ilex verticillata (common winterberry)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry)

- Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf)

-

Herbs

- Carex canescens ssp. canescens (typical hoary sedge)

- Carex stricta (tussock sedge)

- Carex vesicaria (lesser bladder sedge)

- Drosera rotundifolia (round-leaved sundew)

- Dulichium arundinaceum var. arundinaceum (three-way sedge)

- Hypericum virginicum (Virginia marsh St. John's-wort)

- Juncus effusus ssp. solutus (common soft rush)

- Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. cinnamomeum (cinnamon fern)

- Scirpus cyperinus (common wool-grass)

- Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens (marsh fern)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Sphagnum fallax

- Sphagnum magellanicum

- Sphagnum papillosum

-

Submerged aquatics

- Potamogeton spp.

Similar Ecological Communities

- Coastal plain pond

(guide)

In New York, coastal plain ponds are restricted to Long Island and are most common in the Central Pine Barrens. The ponds are generally larger than pine barrens vernal ponds and reveal a distinct zonation of vegetation on the pond shore as the water draws down. Coastal plain ponds may hold water throughout the year and the larger examples may support fish. Pine barrens vernal ponds may also have a distinct zonation of vegetation, but these wetlands can draw down completely in late summer and are always fishless.

- Eutrophic pond

(guide)

Eutrophic ponds are permanently flooded and do not completely draw down. Eutrophic ponds usually have an inlet and an outlet, and they support fish.

- Intermittent stream

(guide)

Pine barrens vernal ponds form in depressions with no inlet or outlet, whereas intermittent streams flow down hill in a linear stream bed. Both are ephemeral aquatic communities that usually dry up as the season progresses, and they share many species that depend on intermittent flooding.

- Vernal pool

(guide)

Pine barrens vernal pools are larger (>1.0 acre) than vernal pools, surrounded by fire-adapted pine barren communities, and have vegetation that is usually well-developed and distinct from vernal pool vegetation. Individual vernal pools are typically small (<0.5 acre), are surrounded by upland forest with trees that overhang the pool, providing a continuous leaf litter substrate, and are generally sparsely vegetated. The two communities are similar in that they provide habitat for many of the same animals that depend on seasonally flooded depressions to breed.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Pine Barrens Vernal Pond. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Bried, J.T. and G.J. Edinger. 2009. Baseline floristic and classification of pine barrens vernal ponds. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 136(1): 128-136.

Comer, P. K. Goodin, G. Hammerson, S. Menard, M. Pyne, M.Reid, M. Robles, M. Russo, L. Sneddon, K. Sno, A. Tomaino, and M. Tuffy. 2005. Biodiversity Values of Geographically Isolated Wetlands: An Analysis of 20 U.S. States. NatureServe, Arlington, VA.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Hunsinger, K.C. 1999. A survey of the amphibians and reptiles of the Albany Pine Bush. M.S. Thesis submitted to the University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, NY.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Williams, D.D. 2001. The Ecology of Temporary waters. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, New Jersey.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Jennifer Garrett

Information for this guide was last updated on: April 3, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Pine barrens vernal pond.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/pine-barrens-vernal-pond/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.