Maritime Heathland

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Open Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S1

Critically Imperiled in New York - Especially vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to extreme rarity or other factors; typically 5 or fewer populations or locations in New York, very few individuals, very restricted range, very few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or very steep declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3

Vulnerable globally - At moderate risk of extinction due to rarity or other factors; typically 80 or fewer populations or locations in the world, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

Summary

Did you know?

Dune heathlands and other coastal heathlands in New York are maintained by salt spray, wind, and frost that lingers in shallow hollows. Historical clearing, grazing, and fire probably didn't affect the extent of the dune heath communities, but they did increase the acreage of heathlands in some locations, including small pockets across eastern Long Island and the expansive heathlands of Nantucket.

State Ranking Justification

There are very few documented occurrences of this community; some have good viability and are on public or private conservation land. The community is restricted to the Coastal Lowlands ecozone of eastern Long Island in Suffolk County and is only documented from the South Fork. The trend for the community is suspected to be stable to declining; primary threats are from recreational overuse by all-terrain vehicles.

Short-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of maritime heathlands is suspected to be stable to decreasing, primarily due to recreational overuse and development pressures and possibly due to fire suppression and woody species invasion.

Long-term Trends

The number, extent, and viability of maritime heathland in New York are suspected to have declined substantially over the long-term. These declines are likely correlated with coastal development and associated changes in landscape connectivity and natural processes. Declines may also be due to fire suppression; particularly in inland portions of the heathland, fire may have historically kept woody species at bay.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Maritime heathland is primarily threatened by recreational overuse of four-wheel drive vehicles and all-terrain vehicles. Development pressures and use of herbicides are additional threats.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Restore and replicate the natural fire regime, as appropriate. Monitor for extensive all-terrain vehicle use and trampling damage. Fencing and signage may be necessary to restrict vehicle access. Monitor the abundance of invasive species in this community and, as needed, control their encroachment.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

This community is best protected as part of a large maritime system, encompassing grasslands, shrublands, bluffs, heathland, forests, barrens, and dunes. Development should avoid fragmentation of such systems to allow for nutrient flow, seed dispersal, and seasonal animal migrations within them. Bisecting trails, roads, and developments can also allow exotic plant and animal species to invade and potentially increase 'edge species' (such as raccoons, skunks, and foxes). Connectivity to brackish and freshwater tidal communities and to shallow offshore communities should also be maintained as much as possible to maintain "maritime" conditions, which imply deposition of salt spray and shearing from offshore winds.

Inventory Needs

Surveys and documentation of additional occurrences are needed, as are data on rare and characteristic animals. Plot data collection from known sites is also needed.

Research Needs

Documentation of the natural fire regime of this community is needed. An investigation into the taxonomic distinction between interdunal areas dominated by heath shrubs (currently classified as a stabilized maritime dune variant) and maritime heathland is needed, as the two can be essentially identical in species composition, structure, and function. The two types need further documentation, analysis and clarification.

Rare Species

- Abagrotis benjamini (Coastal Heathland Cutworm) (guide)

- Amelanchier nantucketensis (Nantucket Juneberry) (guide)

- Apamea burgessi (Burgess's Apamea) (guide)

- Apamea inordinata (Irregular Apamea) (guide)

- Catocala jair ssp. 2 (Jersey Jair Underwing) (guide)

- Cisthene packardii (Packard's Lichen Moth) (guide)

- Coelodasys apicalis (Plain Schizura) (guide)

- Corema conradii (Broom Crowberry) (guide)

- Crocanthemum dumosum (Bushy Rock Rose) (guide)

- Derrima stellata (Pink Star Moth) (guide)

- Dichagyris acclivis (Switchgrass Dart) (guide)

- Eacles imperialis imperialis (Imperial Moth) (guide)

- Empetrum nigrum (Black Crowberry) (guide)

- Euchlaena madusaria (A Geometrid Moth) (guide)

- Eucoptocnemis fimbriaris (Fringed Dart) (guide)

- Euxoa pleuritica (Fawn Brown Dart) (guide)

- Euxoa violaris (Violet Dart) (guide)

- Ilexia intractata (Black-dotted Ruddy) (guide)

- Liatris scariosa var. novae-angliae (Northern Blazing Star) (guide)

- Marimatha nigrofimbria (Black-bordered Lemon Moth) (guide)

- Oligia bridghamii (Bridgham's Brocade) (guide)

- Psectraglaea carnosa (Pink Sallow) (guide)

- Schinia spinosae (Spinose Flower Moth) (guide)

- Spiranthes vernalis (Grass-leaved Ladies' Tresses) (guide)

- Zale lunifera (Pine Barrens Zale) (guide)

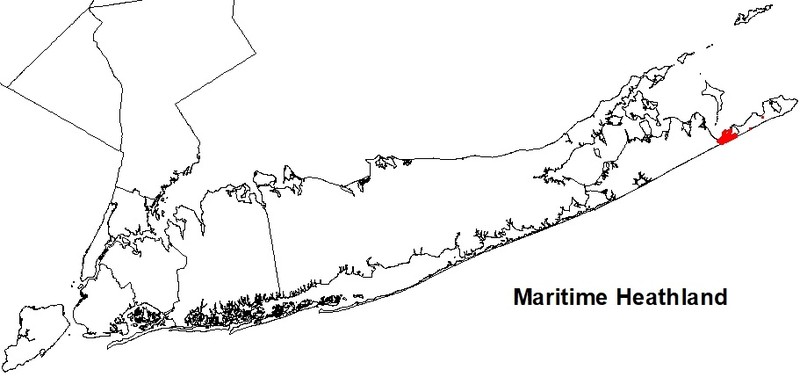

Range

New York State Distribution

This community is restricted to the Coastal Lowlands ecozone of eastern Long Island in Suffolk County on the South Fork. The historical range may have extended west into the south-central part of Long Island.

Global Distribution

This community is known from the Northern Atlantic coast of Massachusetts and New York (NatureServe 2009).

Best Places to See

- Napeague State Park (Suffolk County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A dwarf shrubland community that occurs on rolling outwash plains and moraine of the glaciated portion of the Atlantic coastal plain, near the ocean and within the influence of onshore winds and salt spray. Typical examples of this community are dominated by low heath or heath-like shrubs that collectively have greater than 50% cover. A few examples may be sparsely vegetated by the same heath shrubs. This community intergrades with maritime grassland, and the two communities may occur together in a mosaic.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

Characteristic shrubs include bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), beach heather (Hudsonia tomentosa), blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), and beach-plum (Prunus maritima). Grasses and forbs are present, but they do not form a turf; characteristic species include common hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvancica), rush (Juncus greenei), bushy aster (Symphyotrichum dumosum), stiff-leaf aster (Ionactis linariifolius), flax-leaf white-topped aster (Sericocarpus linifolius), bushy rockrose (Helianthemum dumosum), and New England blazing star (Liatris scariosa var. novae-angliae). A characteristic bird in winter is the yellow-rumped warbler (Dendroica coronata).

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 4 feet and 20 feet.

Best Time to See

Summer presents great opportunities to pick ripening fruits from the abundant blueberries and huckleberries that can be found in this natural community.

Maritime Heathland Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Black Huckleberry - Lowbush Blueberry - Bearberry / Shore Little Bluestem Dwarf-shrubland (CEGL006066)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain Heathland and Grassland (CES203.895)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (bearberry)

- Gaylussacia baccata (black huckleberry)

- Hudsonia tomentosa (beach-heather)

- Morella caroliniensis (bayberry)

- Pinus rigida (pitch pine)

- Vaccinium angustifolium (common lowbush blueberry)

-

Vines

- Rubus flagellaris (northern dewberry)

- Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans (eastern poison-ivy)

-

Herbs

- Avenella flexuosa (common hair grass)

- Carex pensylvanica (Pennsylvania sedge)

- Panicum virgatum (switch grass)

- Schizachyrium scoparium var. scoparium (little bluestem)

- Solidago sempervirens (northern seaside goldenrod)

- Symphyotrichum dumosum (bushy-aster)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Maritime dunes

(guide)

Broadly, maritime dunes occur on shifting sands closer to the ocean that are occassionally overwashed by extreme storm events and are dominated by a near monoculture of beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata). Beachgrass is uncommon in maritime heathlands, which are located within the zone of maritime influence but tend to occur further inland. The species composition, structure, and function of stabilized maritime dunes and maritime heathland, however, can be nearly identical.

- Maritime grassland

(guide)

As the name implies, maritime grassland is dominated by grasses and forbs, whereas maritime heathland is dominated by dwarf shrubs. The two communities often occur together in a mosaic.

- Maritime shrubland

(guide)

Maritime heathland, unlike maritime shrubland, is characterized by dwarf shrubs, including beach heather, bearberry, blueberry, and black huckleberry. Maritime shrublands are dominated by tall expanses of bayberry, arrowwood, and shadbush shrubs. The two communities grade into each other and are distinguished primarily based on shrub height.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maritime Heathland. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Dunwiddie, Peter W., R.E. Zaremba, K.A. Harper. 1996. A classification of coastal heathlands and sandplain grasslands in Massachusetts. Rhodora 98(894): 117-145.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Data last updated October, 2009)

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Thompson, John E. 1997. Ecological communities of the Montauk Peninsula, Suffolk County, New York. Prepared for The Nature Conservancy, Long Island Chapter. April 1997.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: December 12, 2023

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maritime heathland.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maritime-heathland/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.