Medium Fen

- System

- Palustrine

- Subsystem

- Open Peatlands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S2S3

Imperiled or Vulnerable in New York - Very vulnerable, or vulnerable, to disappearing from New York, due to rarity or other factors; typically 6 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines. More information is needed to assign either S2 or S3.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G3G4

Vulnerable globally, or Apparently Secure - At moderate risk of extinction, with relatively few populations or locations in the world, few individuals, and/or restricted range; or uncommon but not rare globally; may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors. More information is needed to assign either G3 or G4.

Summary

Did you know?

One of the dominant plants in medium fens is sweet gale (Myrica gale). Historically, sweet gale was used to flavor beer. Today, most brewers use hops. However, in the middle ages, sweet gale was the most efficient and cheap flavoring. Beer was also flavored with fennel, mint, juniper, and rosemary, as well as gale, to improve the durability as well as the taste. Sweet gale is also used as a spice in soups and stews, like bay leaves. Their catkins, or cones, produce a wax when boiled in water that can be used to make candles.

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and many are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is limited to the calcareous areas of the state, and includes several large, high quality examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure or alteration to the natural hydrology.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of medium fens in New York have probably remained stable in recent decades as a result of wetland protection regulations. There may be a few slight losses due to alteration of hydrology by impoundments (converting to sedge meadow or another palustrine type).

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of medium fens in New York have probably declined moderately from historical numbers likely correlated with the onset of agricultural and residential development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Medium fens are threatened by development and its associated run-off (e.g., residential, agricultural, roads, railroads), recreational overuse (e.g., hiking trails) and habitat alteration in the adjacent landscape (e.g., logging, clearing, mining, pollution). Alteration to the natural hydrology is also a threat to this community (e.g., impoundments, ditching, stream channelization, dredging, blocked culverts, beaver). Several examples of medium fen are threatened by invasive species, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), reed grass (Phragmites australis), and buckthorns (Rhamnus spp.).

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Consider how water flows around and into this wetland. As most of the water inputs are from underground, management for the prevention of altered water quality and quantity is particularly difficult for this natural community, but also of utmost priority. Projects that occur near this community must consider the proximity of the development to this wetland and the potential for changing how water flows, both aboveground and belowground, into this wetland. Concerning the proximity to the wetland, terrestrial buffers provide nesting habitat for resident salamanders, frogs, and turtles, and additional food sources for locally nesting birds. Consultation with a hydrologist is important to determine patterns of run-off and underground water sources for the wetland; in addition, impervious surfaces that rapidly divert water to the wetland should be avoided. Rapid influxes of surface water dilute the limey, mineral rich waters, decrease the robustness of the native fen species, and increase the likelihood of invasion by non-native species.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

When considering road construction and other development activities minimize actions that will change what water carries and how water travels to this community, both on the surface and underground. Water traveling over-the-ground as run-off usually carries an abundance of silt, clay, and other particulates during (and often after) a construction project. While still suspended in the water, these particulates make it difficult for aquatic animals to find food; after settling to the bottom of the wetland, these particulates bury small plants and animals and alter the natural functions of the community in many other ways. Thus, road construction and development activities near this community type should strive to minimize particulate-laden run-off into this community. Water traveling on the ground or seeping through the ground also carries dissolved minerals and chemicals. Road salt, for example, is becoming an increasing problem both to natural communities and as a contaminant in household wells. Fertilizers, detergents, and other chemicals that increase the nutrient levels in wetlands cause algae blooms and eventually an oxygen-depleted environment where few animals can live. Herbicides and pesticides often travel far from where they are applied and have lasting effects on the quality of the natural community. So, road construction and other development activities should strive to consider: 1. how water moves through the ground, 2. the types of dissolved substances these development activities may release, and 3. how to minimize the potential for these dissolved substances to reach this natural community.

Inventory Needs

Additional inventory efforts in regions with calcareous bedrock and promising wetlands will likely turn up a few additional sites. Re-inventories of known sites will provide important information to help assess short and long-term changes. Survey fens that provide habitat for rare species. For example, extant bog turtle sites should be surveyed to determine the type and quality of natural community if unknown.

Research Needs

Research better ways to accurately and efficiently measure and understand groundwater hydrology of fens. Further research into determining the proportion of fen water inputs is needed (e.g., groundwater vs. surface). If a fen is strongly groundwater influenced, traditional wetland buffers aimed at reducing surface water run-off may not sufficiently protect fen groundwater hydrology.

Rare Species

- Arethusa bulbosa (Dragon's Mouth Orchid) (guide)

- Calamagrostis stricta (Northern Reed Grass) (guide)

- Carex chordorrhiza (Creeping Sedge) (guide)

- Carex livida (Livid Sedge) (guide)

- Carex meadii (Mead's Sedge) (guide)

- Circus hudsonius (Northern Harrier) (guide)

- Cistothorus stellaris (Sedge Wren) (guide)

- Cypripedium candidum (Small White Lady's Slipper) (guide)

- Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding's Turtle) (guide)

- Equisetum palustre (Marsh Horsetail) (guide)

- Fagitana littera (Marsh Fern Moth) (guide)

- Glyptemys muhlenbergii (Bog Turtle) (guide)

- Hemileuca maia menyanthevora (Bogbean Buckmoth) (guide)

- Lycopus rubellus (Stalked Bugleweed) (guide)

- Macropis nuda (Common Loosestrife Oil Bee) (guide)

- Phlox maculata ssp. maculata (Wild Sweet William) (guide)

- Salix pyrifolia (Balsam Willow) (guide)

- Scheuchzeria palustris (Pod Grass) (guide)

- Sparganium natans (Small Bur-reed) (guide)

- Sphagnum andersonianum (Anderson's Peat Moss) (guide)

- Sphagnum subfulvum (Pale Peat Moss) (guide)

- Symphyotrichum boreale (Northern Bog Aster) (guide)

- Trollius laxus (Spreading Globeflower) (guide)

- Williamsonia fletcheri (Ebony Boghaunter) (guide)

Range

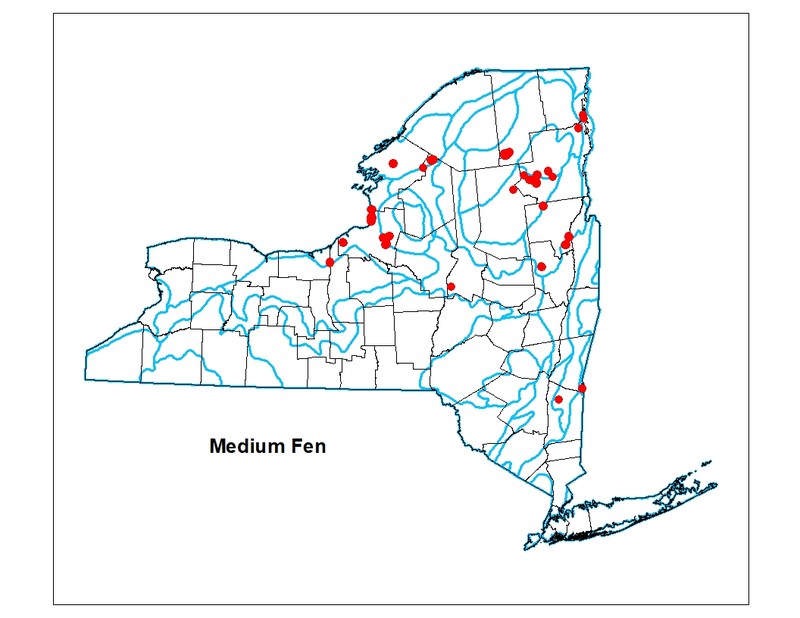

New York State Distribution

This community is currently known from the Eastern Ontario Lake Plain, the Tug Hill Plateau, the St. Lawrence Valley, Lake Champlain Valley, the Central Adirondacks, and the southern end of Lake George. Single examples are known from the Mohawk Valley and the Hudson Valley. Additional occurrences may be located elsewhere in the state where similar environmental conditions are possible.

Global Distribution

The range of the physically broadly-defined community may be worldwide. Examples with the greatest biotic affinities to New York occurrences are suspected to span north to southern Canada, west to Minnesota and Illinois, south probably at least to Virginia, and northeast to Maine.

Best Places to See

- Taconic State Park

- Wickham Marsh Wildlife Management Area, Adirondack Park

- Oswego State Forest (Oswego County)

- Ausable Marsh Wildlife Management Area, Adirondack Park

- Perch River Wildlife Management Area (Jefferson County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A moderately minerotrophic peatland (intermediate between rich fens and poor fens) in which the substrate is a mixed peat composed of graminoids, mosses, and woody species. Medium fens are fed by waters that are moderately mineralized, with pH values generally ranging from 4.5 to 6.5. Medium fens often occur as a narrow transition zone between an aquatic community and either a swamp or an upland community along the edges of streams and lakes. In medium fens, the herbaceous layer, dominated by the sedge Carex lasiocarpa, typically forms a canopy that overtops the low shrub layer. The physiognomy of medium fens may range from a dwarf shrubland to a perennial grassland, and be either shrub-dominated, herb dominated or have roughly equal amounts of shrubs and herbs.

Characters Most Useful for Identification

The dominant species in medium fens are usually wooly fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa) and sweet-gale (Myrica gale). In addition to sweet-gale, characteristic shrubs include leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), bog rosemary (Andromeda glaucophylla), speckled alder (Alnus incana ssp. rugosa), cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon), and young red maple (Acer rubrum). In addition to the sedge Carex lasiocarpa, characteristic herbs include marsh St. John's-wort (Triadenum virginicum), pitcher-plant (Sarracenia purpurea), milfoil bladderwort (Utricularia intermedia), sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), white beakrush (Rhynchospora alba), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), arrowleaf (Peltandra virginica), rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides), grass pink (Calopogon tuberosus), swamp goldenrod (Solidago uliginosa), royal fern (Osmunda regalis), three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), common cat-tail (Typha latifolia), and sundew (Drosera intermedia). A characteristic moss is Calliergonella cuspidata. Other nonvascular plants found in medium fens include the mosses Aulacomnium palustre, Bryum pseudotriquetrum, Calliergon giganteum, Campylium stellatum, several peat mosses (Sphagnum contortum, S. magellanicum, S. subsecundum), and the thalloid liverwort Aneura pinguis. The major rich fen indicators scorpion feather moss (Scorpidium scorpioides) and Scorpidium revolvens are absent (Slack 1994). A rare moth of some medium fens is bog buckmoth (Hemileuca sp.), which feeds on buckbean. Odonates, such as the brush-tipped emerald (Somatochlora walshii), are characteristic of some medium fens.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 95 feet and 2,001 feet.

Best Time to See

Many of the characteristic species flower in June and July, making these months good times to visit this community.

Medium Fen Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Woolly-fruit Sedge - (Beaked Sedge) - Water Horsetail Fen (CEGL005229)

- Leatherleaf - Sweetgale / Woolly-fruit Sedge Fen (CEGL005228)

- Sweetgale - Leatherleaf / (Woolly-fruit Sedge, Northwest Territory Sedge) - Bladderwort species Fen (CEGL006302)

- Sweetgale - White Meadowsweet - Leatherleaf Fen (CEGL006512)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Laurentian-Acadian Alkaline Fen (CES201.585)

- North-Central Interior and Appalachian Acidic Peatland (CES202.606)

Characteristic Species

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer rubrum var. rubrum (common red maple)

-

Shrubs < 2m

- Alnus incana ssp. rugosa (speckled alder)

- Andromeda polifolia var. glaucophylla

- Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry)

- Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf)

- Myrica gale (sweet gale)

- Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry)

-

Herbs

- Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana (slender bog sedge)

- Comarum palustre (marsh-cinquefoil)

- Drosera rotundifolia (round-leaved sundew)

- Hypericum virginicum (Virginia marsh St. John's-wort)

- Menyanthes trifoliata (buck-bean)

- Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis (royal fern)

- Pogonia ophioglossoides (rose pogonia)

- Sarracenia purpurea (purple pitcherplant)

- Solidago uliginosa (bog goldenrod)

- Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens (marsh fern)

- Typha latifolia (wide-leaved cat-tail)

- Utricularia intermedia (flat-leaved bladderwort)

-

Nonvascular plants

- Calliergonella cuspidata

Similar Ecological Communities

- Dwarf shrub bog

(guide)

Dwarf shrub bogs are dominated by shrubs (<1 m tall) in the heath family (Ericaceae). Leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata) is typically dominant with lesser amounts of sheep laurel (Kalmia angustifolia), bog laurel (Kalmia polifolia), Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum), bog rosemary (Andromeda polifolia), black huckleberry (Gaylusaccia baccata), with blueberries and cranberries (Vaccinium spp.). Medium fens are usually dominated, or co-dominated, by woolly-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana) and sweet-gale (Myrica gale) in the bayberry family (Myricaceae) with lesser amounts of the heath shrubs listed above. Medium fens may range from a dwarf shrubland dominated by sweet gale to a perennial grassland dominated by wooly-fruited sedge, or have roughly equal amounts of shrubs and herbs. Medium fens tend to have higher pHs (4.5 to 6.5) than dwarf shrub bogs.

- Inland poor fen

(guide)

Inland poor fens are weakly minerotrophic peatlands with a substrate composed primarily of Sphagnum moss with scattered sedges, shrubs, and stunted trees. Although woolly-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana) and sweet gale (Myrica gale) can sometimes be found in inland poor fens, they are not dominant. Medium fens tend to have slightly higher pHs (4.5 to 6.5 versus 3.5 to 5.0) than inland poor fens.

- Rich graminoid fen

(guide)

Rich graminoid fens have less than 50% cover by shrubs, are more floristically diverse than medium fens and are not dominated or co-dominated by woolly-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana). Rich graminoid fens tend to have higher pHs (6.0 to 7.8 versus 4.5 to 6.5) than medium fens.

- Rich shrub fen

(guide)

In rich shrub fens Sphagnum is generally absent, or only the most nutrient demanding species are present as a minor component. In addition, the dominant shrubs require a moderately high availability of minerals, such as alderleaf buckthorn (Rhamnus alnifolia), shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora floribunda), poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), hoary willow (Salix candida), and bog birch (Betula pumila). Rich shrub fens grade into medium fens where herbaceous species (especially Carex lasiocarpa) form a canopy over the dwarf shrubs and the cover of species that are tolerant of lower mineral availability such as sweet gale (Myrica gale), and leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata) exceeds that of more nutrient demanding species.

- Sedge meadow

(guide)

Sedge meadows are open wetlands dominated by fibrous peat (at least 20 cm deep) and tussock-forming sedges, such as tussock sedge (Carex stricta), which has at least 50% cover. The most common associate is bluejoint grass (Calamagrostis canadensis). Other associates include other sedges (Scirpus spp., Carex spp., Eleocharis spp., Dulichium arundinaceum), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), manna grasses (Glyceria spp.), and sparsely distributed shrubs (Alnus spp., Spiraea spp.). Medium fens are usually dominated, or co-dominated, by woolly-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa ssp. americana) and sweet-gale (Myrica gale) in the bayberry family (Myricaceae) with lesser amounts of the heath shrubs.

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Medium Fen. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Andrus, R.E. 1980. Sphagnaceae (Peat Moss Family) of New York State. Bulletin No. 442. New York State Museum. Albany, NY.

Bailey, K. and B.L. Bedford. 1999. Response of fen vegetation to variation in hydrochemical inputs. Unpublished report. Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Godwin, K.S., J.P. Shallenberger, D.J. Leopold, and B.L. Beford. 2000. Linking landscape parameters to local hydrogeologic gradients and plant species occurrence in New York fens: A hydrogeologic setting (HGS) framework. Unpublished draft manuscript. December 20, 2000.

Johnson, A.M. and D.J. Leopold. 1994. Vascular plant species richness and rarity across a minerotrophic gradient in wetlands of St. Lawrence County, New York, USA. Biodiversity Conserv. 3:606-627.

Langdon, Stephen F., M. Dovciak, and D.J. Leopold. 2020. Tree Encroachment Varies by Plant Community in a Large Boreal Peatland Complex in the Boreal-Temperate Ecotone of Northeastern USA. Wetlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-020-01319-z

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 1995. Freshwater Wetlands: Delineation Manual. July 1995. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Division of Fish, Wildlife, and Marine Resources. Bureau of Habitat. Albany, NY.

Olivero, Adele M. 2001. Classification and Mapping of New York's Calcareous Fen Communities. A summary report prepared for the Nature Conservancy - Central/Western New York Chapter with funding from the Biodiversity Research Institute. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 28 pp. plus nine appendices.

Olivero, Adele. 2002. Survey of Eastern New York's calcareous fens in the Mount Everett-Mount Riga landscape. A report prepared for the Nature Conservancy Eastern New York Chapter. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 31 pp. plus appendices.

Podniesinski, G. 1994. An ecological model for the fens of the Deer Creek Marsh complex. Unpublished report prepared for The Nature Conservancy. State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, New York. April 28, 1994.

Reschke, Carol, B. Bedford, N. Slack, and F.R. Wesley. 1990. Fen Vegetation of New York State. A poster presented of July 31, 1990 at the Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting, Snowbird, Utah.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

Slack, Nancy G. 1994. Can one tell the mire type from the bryophytes alone? J. Hattori Bot. Lab 75:149-159.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: March 26, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Medium fen.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/medium-fen/.

Accessed July 26, 2024.