Maple-Basswood Rich Mesic Forest

- System

- Terrestrial

- Subsystem

- Forested Uplands

- State Protection

- Not Listed

Not listed or protected by New York State.

- Federal Protection

- Not Listed

- State Conservation Status Rank

- S3

Vulnerable in New York - Vulnerable to disappearing from New York due to rarity or other factors (but not currently imperiled); typically 21 to 80 populations or locations in New York, few individuals, restricted range, few remaining acres (or miles of stream), and/or recent and widespread declines.

- Global Conservation Status Rank

- G4

Apparently Secure globally - Uncommon in the world but not rare; usually widespread, but may be rare in some parts of its range; possibly some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Summary

Did you know?

Basswood's fibrous inner bark was the source of fiber for ropes, mats, fishnets, and baskets constructed by Native Americans and settlers. The soft, light, easily-worked wood was once the wood of choice for prosthetic limbs and is now still valued as excellent hand-carving wood.

State Ranking Justification

There are several hundred to a few thousand occurrences statewide. Some documented occurrences have good viability and many are protected on public land or private conservation land. This community is somewhat limited to the calcareous regions of the state, and includes several very large, high quality, old-growth examples. The current trend of this community is probably stable for occurrences on public land, or declining slightly elsewhere due to moderate threats related to development pressure. This community has declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with past logging, agiculture, and other development.

Short-term Trends

The number and acreage of maple-basswood rich mesic forests in New York have probably declined moderately in recent decades as a result of logging, agriculture, and development.

Long-term Trends

The number and acreage of maple-basswood rich mesic forests in New York have probably declined substantially from historical numbers likely correlated with past logging, agiculture, and development.

Conservation and Management

Threats

Threats to forests in general include changes in land use (e.g., clearing for development), forest fragmentation (e.g., roads), and invasive species (e.g., insects, diseases, and plants). Other threats may include over-browsing by deer, and air pollution (e.g., ozone and acidic deposition). When occurring in expansive forests, the largest threat to the integrity of maple-basswood rich mesic forests are activities that fragment the forest into smaller pieces. These activities, such as road building and other development, restrict the movement of species and seeds throughout the entire forest, an effect that often results in loss of those species that require larger blocks of habitat (e.g., black bear, bobcat, certain birds). Additionally, fragmented forests provide decreased benefits to neighboring societies from services upon which these societies often substantially depend (e.g., clean water, mitigation of floods and droughts, pollination in agricultural fields, and pest control) (Daily et al. 1997). Maple-basswood rich mesic forests are threatened by development (e.g., residential, agricultural), either directly within the community or in the surrounding landscape. Other threats include habitat alteration (e.g., roads, excessive logging, mining, deer over-browsing, plantations), and recreational overuse (e.g., ATVs, hiking and cross-county ski trails, campgrounds, horseback riding, mountain biking). Illegal dumping is a threat to at least one example. Pesticide use may be a threat to non-target insects in a few examples. Several maple-basswood rich mesic forests are threatened by invasive species, such as buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), shrubby honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii), garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), black swallow-wort (Cynanchum louiseae), field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) is an Asian beetle that infests and kills North American ash trees. All native ash trees are susceptible, including white ash, green ash, and black ash. In New York, emerald ash borer has been found mostly south of the Adirondack Mountains, but in 2017 it was recorded in Franklin and St. Lawrence Counties. Natural communities dominated or co-dominated by ash trees would likely be most impacted by emerald ash borer invasion.

Conservation Strategies and Management Practices

Management should focus on activities that help maintain regeneration of the species associated with this community. Deer have been shown to have negative effects on forest understories (Miller et al. 1992, Augustine & French 1998, Knight 2003) and management efforts should strive to ensure that regenerating trees and shrubs are not so heavily browsed that they cannot replace overstory trees. Avoid cutting old-growth examples and encourage selective logging areas that are under active forestry.

Development and Mitigation Considerations

Strive to minimize fragmentation of large forest blocks by focusing development on forest edges, minimizing the width of roads and road corridors extending into forests, and designing cluster developments that minimize the spatial extent of the development. Development projects with the least impact on large forests and all the plants and animals living within these forests are those developments built on brownfields or other previously developed land. These projects have the added benefit of matching sustainable development practices (for example, see: The President's Council on Sustainable Development 1999 final report, US Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification process at http://www.usgbc.org/).

Inventory Needs

Inventory any remaining large and old-growth examples across the state. Survey for occurrences statewide to advance documentation and classification of maple-basswood rich mesic forests. A statewide review of maple-basswood rich mesic forests is desirable. Continue searching for large sites in good condition (A- to AB-ranked).

Research Needs

Critically compare this community to beech-maple mesic forest and confirm that occurrences of each are properly classified.

Rare Species

- Agastache nepetoides (Yellow Giant Hyssop) (guide)

- Agrimonia rostellata (Woodland Agrimony) (guide)

- Aplectrum hyemale (Puttyroot) (guide)

- Asplenium scolopendrium var. americanum (Hart's-tongue Fern) (guide)

- Astragalus neglectus (Cooper's Milkvetch) (guide)

- Botrychium oneidense (Blunt-lobed Grape Fern) (guide)

- Cardamine douglassii (Purple Spring Cress) (guide)

- Carex careyana (Carey's Sedge) (guide)

- Carex davisii (Davis' Sedge) (guide)

- Carex formosa (Handsome Sedge) (guide)

- Carex jamesii (James' Sedge) (guide)

- Carex striatula (Lined Sedge) (guide)

- Chamaelirium luteum (Fairywand) (guide)

- Cirriphyllum piliferum (Hair-pointed Moss) (guide)

- Crotalus horridus (Timber Rattlesnake) (guide)

- Cypripedium candidum (Small White Lady's Slipper) (guide)

- Cystopteris protrusa (Lowland Fragile Fern) (guide)

- Erigenia bulbosa (Harbinger-of-spring) (guide)

- Frasera caroliniensis (Green Gentian) (guide)

- Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Bald Eagle) (guide)

- Hydrangea arborescens (Wild Hydrangea) (guide)

- Hydrastis canadensis (Goldenseal) (guide)

- Jeffersonia diphylla (Twinleaf) (guide)

- Lasiurus borealis (Eastern Red Bat) (guide)

- Lindbergia brachyptera (Papillose Fine-branch Moss) (guide)

- Melanerpes erythrocephalus (Red-headed Woodpecker) (guide)

- Monarda clinopodia (Basilbalm) (guide)

- Myotis leibii (Eastern Small-footed Myotis) (guide)

- Myotis lucifugus (Little Brown Bat) (guide)

- Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) (guide)

- Perimyotis subflavus (Tri-colored Bat) (guide)

- Pieris virginiensis (West Virginia White) (guide)

- Poa sylvestris (Forest Blue Grass) (guide)

- Pseudotaxiphyllum distichaceum (Two-ranked moss) (guide)

- Ptelea trifoliata ssp. trifoliata (Wafer-ash) (guide)

- Setophaga cerulea (Cerulean Warbler) (guide)

- Trillium flexipes (Nodding Trillium) (guide)

- Triphora trianthophora (Nodding Pogonia) (guide)

- Ulmus thomasii (Rock Elm) (guide)

- Veronicastrum virginicum (Culver's Root) (guide)

Range

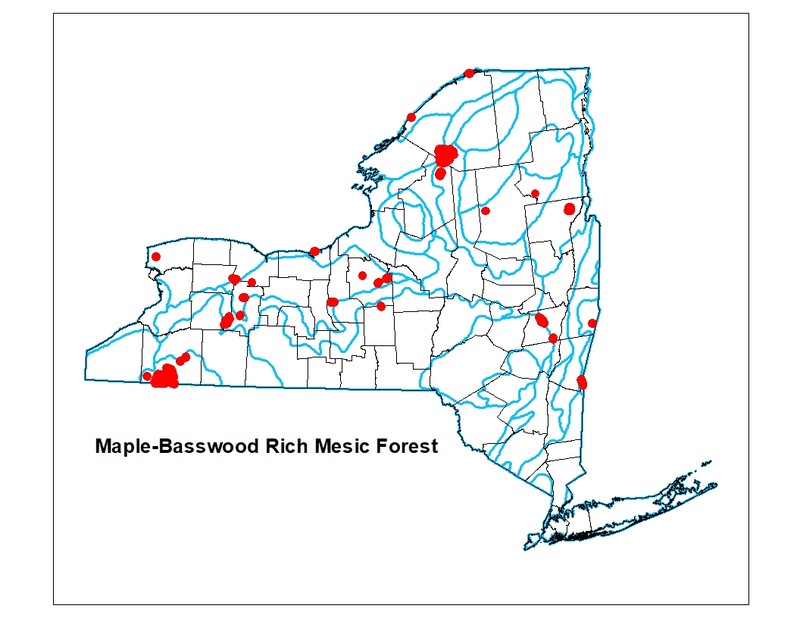

New York State Distribution

This community is currently known from calcareous areas across the Ontario Lake Plain, the St. Lawrence Valley, and the Adirondack Mountains. Maple-basswood rich mesic forests are also known from the Taconic Mountains and along the Helderberg Escarpment. Several high quality examples are known from the unglaciated section of the High Allegheny Plateau within Allegany State Park.

Global Distribution

This somewhat broadly-defined community probably occurs throughout the Northeast U.S., but is absent or restricted to very small patches along the Atlantic coast. It is widespread in the Great Lakes basin, where it is concentrated. The range is estimated to span north to southern Ontario, west to Minnesota, southwest to Indiana and Ohio, south to Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and east to Massachusetts and Maine.

Best Places to See

- Letchworth State Park (Livingston, Wyoming Counties)

- Green Lakes State Park (Onondaga County)

- Joralemon Town Park

- Vanderwhacker Mountain Wild Forest, Adirondack Park

- Taconic State Park

- Holts Run Highlands, Allegany State Park

- Moose River Wild Forest, Adirondack Park (Hamilton County)

Identification Comments

General Description

A species-rich hardwood forest that typically occurs on well-drained, moist soils of circumneutral pH. Rich-soil herbs are predominant in the ground layer and are usually correlated with calcareous bedrock, although bedrock does not have to be exposed. Where bedrock outcrops are lacking, surficial features such as seeps are often present. The dominant trees are sugar maple (Acer saccharum), basswood (Tilia americana), and white ash (Fraxinus americana).

Characters Most Useful for Identification

This community is identified by a consistent presence and abundance of basswood in association with sugar maple and the high diversity of rich-soil herbaceous species, including a good display of spring ephemerals. The diverse flora of rich herbs (especially ferns) including maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum), bulblet fern (Cystopteris bulbifera), Goldie's fern (Dryopteris goldiana), silvery spleenwort (Deparia acrostichoides), glade fern (Diplazium pycnocarpon), and plantain-sedge (Carex plantaginea) solidly identify this community. This diversity of rich overstory and understory plants is usually correlated with calcareous, or possibly circumneutral bedrock, and a soil pH greater than 5.0.

Elevation Range

Known examples of this community have been found at elevations between 230 feet and 2,260 feet.

Best Time to See

Because the key to distinguishing a maple-basswood rich mesic forest from related types is its vascular plant composition and diversity, it is easiest to identify the community during the growing season, from late May through summer. Striking seasonal leaf color can be enjoyed in the fall.

Maple-Basswood Rich Mesic Forest Images

Classification

International Vegetation Classification Associations

This New York natural community encompasses all or part of the concept of the following International Vegetation Classification (IVC) natural community associations. These are often described at finer resolution than New York's natural communities. The IVC is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Sugar Maple - White Ash / Mountain Maple / Blue Cohosh Forest (CEGL006636)

- Sugar Maple - American Basswood / Striped Maple / Blue Cohosh Forest (CEGL006637)

NatureServe Ecological Systems

This New York natural community falls into the following ecological system(s). Ecological systems are often described at a coarser resolution than New York's natural communities and tend to represent clusters of associations found in similar environments. The ecological systems project is developed and maintained by NatureServe.

- Laurentian-Acadian Northern Hardwood Forest (CES201.564)

Characteristic Species

-

Trees > 5m

- Acer saccharum (sugar maple)

- Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch)

- Carpinus caroliniana ssp. virginiana (musclewood, ironwood, American hornbeam)

- Fraxinus americana (white ash)

- Ostrya virginiana (hop hornbeam, ironwood)

- Quercus rubra (northern red oak)

- Tilia americana var. americana (American basswood)

-

Shrubs 2 - 5m

- Acer spicatum (mountain maple)

- Cornus alternifolia (pagoda dogwood, alternate-leaved dogwood)

- Hamamelis virginiana (witch-hazel)

-

Herbs

- Actaea pachypoda (white baneberry, doll's-eyes)

- Adiantum pedatum (maidenhair fern)

- Allium tricoccum var. tricoccum (common wild leek)

- Asarum canadense (wild ginger)

- Athyrium angustum (northern lady fern)

- Cardamine diphylla (two-leaved toothwort)

- Carex albursina (white bear sedge)

- Carex plantaginea (plantain-leaved sedge)

- Carex platyphylla (broad-leaved sedge)

- Caulophyllum thalictroides (blue cohosh, late blue cohosh)

- Claytonia virginica (eastern spring-beauty)

- Cystopteris bulbifera (bulblet fern)

- Deparia acrostichoides (silvery spleenwort)

- Dicentra canadensis (squirrel-corn)

- Dicentra cucullaria (Dutchman's breeches)

- Dryopteris goldiana (Goldie's wood fern)

- Dryopteris marginalis (marginal wood fern)

- Erythronium americanum ssp. americanum (yellow trout-lily)

- Geranium robertianum (herb-Robert)

- Homalosorus pycnocarpos (glade fern)

- Hydrophyllum virginianum var. virginianum (Virginia waterleaf)

- Maianthemum racemosum ssp. racemosum (false Solomon's-seal)

- Podophyllum peltatum (may-apple)

- Polystichum acrostichoides (Christmas fern)

- Sanguinaria canadensis (bloodroot)

- Thalictrum dioicum (early meadow-rue)

- Tiarella cordifolia (foamflower)

- Trillium cernuum (nodding trillium)

- Trillium erectum (purple trillium, stinking Benjamin)

Similar Ecological Communities

- Beech-maple mesic forest

(guide)

Maple-basswood rich mesic forests have a higher diversity of rich-soil herbs, including a variety of fern species and many spring ephemerals. Beech-maple mesic forests have more acid-tolerant herbs and ferns, and a slightly lower diversity.

- Limestone woodland

(guide)

Limestone woodlands will usually have a more sparse tree canopy layer, shallower soils, and more limestone outcrops.

- Rich mesophytic forest

(guide)

Rich mesophytic forests occur on the Allegheny Plateau of southern New York, have a more diverse overstory than maple-basswood rich mesic forests, and also have a rich herb component, including such herbs as Canada waterleaf (Hydrophyllum canadense), running strawberry-bush (Euonymus obovata), yellow mandarin (Disporum lanuginosum), and black bugbane (Cimicifuga racemosa).

Vegetation

Percent cover

This figure helps visualize the structure and "look" or "feel" of a typical Maple-Basswood Rich Mesic Forest. Each bar represents the amount of "coverage" for all the species growing at that height. Because layers overlap (shrubs may grow under trees, for example), the shaded regions can add up to more than 100%.

Additional Resources

References

Augustine, A.J. and L.E. French. 1998. Effects of white-tailed deer on populations of an understory forb in fragmented deciduous forests. Conservation Biology 12:995-1004.

Braun, E. Lucy. 1950. Deciduous forests of Eastern North America. Macmillan Publ. Co. Inc., New York, N.Y.

Daily, G.C., S. Alexander, P.R. Ehrlich, L. Goulder, J. Lubchenco, P. Matson, H.A. Mooney, S. Postel, S.H. Schneider, D. Tilman, and G.M. Woodwell. 1997. Ecosystem Services: benefits supplied to human societies by natural ecosystems. Issues In Ecology 2:1-16.

Eaton, S.W. and E.F. Schrot. 1987. A flora of the vascular plants of Cattaraugus County, New York. Bull. Buffalo Society Natural Sci. 31: 1-235.

Edinger, G. J., D. J. Evans, S. Gebauer, T. G. Howard, D. M. Hunt, and A. M. Olivero (editors). 2014. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke’s Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY. https://www.nynhp.org/ecological-communities/

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero (editors). 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. (Draft for review). New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Eyre, F.H. (ed.) 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and Canada. Society of American Foresters. Washington, D.C. 148 pp.

Eyre, F.H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and Canada. Society of American Foresters, Washington, D.C.

Hagan, J.M. and A.A. Whitman. 2004. Late-successional Forest:A disappearing age class and implications for biodiversity. Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences. 4 pp.

Knight, T.M. 2003. Effects of herbivory and its timing across populations of Trillium grandiflorum (Liliaceae). American Journal of Botany 90:1207-1214.

Miller, S.G., S.P. Bratton, and J. Hadidian. 1992. Impacts of white-tailed deer on endangered and threatened vascular plants. Natural Areas Journal 12:67-74.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024. New York Natural Heritage Program Databases. Albany, NY.

Reschke, Carol. 1990. Ecological communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Latham, NY. 96 pp. plus xi.

The President's Council on Sustainable Development. 1999. Towards a Sustainable America: Advancing Prosperity, Opportunity, and a Healthy environment for the 21st Century. Washington, DC. 97 pp. plus appendices.

Links

About This Guide

This guide was authored by: Aissa Feldmann

Information for this guide was last updated on: February 5, 2024

Please cite this page as:

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2024.

Online Conservation Guide for

Maple-basswood rich mesic forest.

Available from: https://guides.nynhp.org/maple-basswood-rich-mesic-forest/.

Accessed July 27, 2024.